From the Chicago Reader (December 19, 1997). — J.R.

Titanic

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by James Cameron

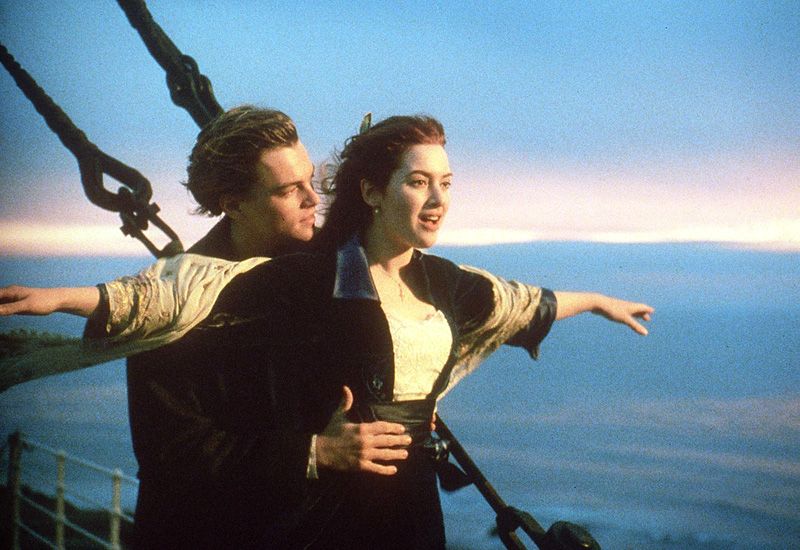

With Leonardo DiCaprio, Kate Winslet, Billy Zane, Kathy Bates, Frances Fisher, Gloria Stuart, Bill Paxton, Bernard Hill, and Suzy Amis.

I suppose there’s something faintly ridiculous about a $200-million movie that argues on behalf of true love over wealth and even bandies about a precious diamond as a central narrative device — like Citizen Kane’s Rosebud — to clinch its point. Yet for all the hokeyness, Titanic kept me absorbed all 194 minutes both times I saw it. It’s nervy as well as limited for writer-director-coproducer James Cameron to reduce a historical event of this weight to a single invented love story, however touching, and then to invest that love story with plot details that range from unlikely to downright stupid. But one clear advantage of paring away the subplots that clog up disaster movies is that it allows one to achieve a certain elemental purity.

This movie tells you a great deal about first class on the ship, a little bit about third class, and nothing at all about second class. According to Walter Lord’s 1955 nonfiction book about the sinking of the Titanic, A Night to Remember, which includes a full passenger list, 279 of the 2,223 passengers were in second class, and 112 of them survived. But as far as Cameron’s story is concerned — a love match between a footloose and penniless artist in third class, Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio), and a rebellious protofeminist woman in first class, Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet), who’s engaged to marry an unscrupulous zillionaire (Billy Zane) — the omission makes perfect sense, even though it establishes that there’s no middle ground between the lovers.

To speak about the artistry of Titanic rather than its economics is to assume that the audience’s pleasure counts for more than the investors’ bank accounts — hardly the assumption that rules the current discourse about the movie. The five-page spread in the December 8 issue of Time magazine includes over three pages devoted to hand-wringing in the lead article, which is headlined “Was all the misery worth it?” That’s followed by Richard Corliss’s negative review, which occupies only two-thirds of one page and concludes, “Ultimately, Titanic will sail or sink not on its budget but on its merits as drama and spectacle. The regretful verdict here: Dead in the water.” Then Cameron is allotted a final page to defend himself, though the obsession with the bottom line in the preceding onslaught forces him to devote nearly all of his rebuttal to production and business details rather than aesthetics. The package could easily have appeared in Forbes, Fortune, or Variety. Yet whose money and whose interests are actually inspiring all this nervousness? Considering the amount of abuse that this movie dishes out to the privileged first-class passengers, isn’t it possible that this is what really has Time so hot and bothered?

I saw Titanic twice at the same theater — first with an audience of “industry people,” including other reviewers, then a couple of weeks later with a less professional crowd — and the difference in the audible responses was palpable. I enjoyed the movie both times, but the second screening, unlike the first, was punctuated by gasps, laughs, and applause in all the right places, suggesting that the second crowd, which had only its own interests at stake, was a lot more receptive. It’s as if I’d sat the first time with the ship’s owners and the second time with the passengers.

Morally and conceptually, this movie could almost have been made in 1912, the year the Titanic sank and the year that D.W. Griffith made Man’s Genesis, The Musketeers of Pig Alley, and The New York Hat. I hasten to add that this was still three years before The Birth of a Nation, the picture that established features as the central attraction of moviegoing, and that there’s nothing about Kate Winslet that suggests either Lillian Gish or Mary Pickford. (If her pulchritude and sass recall any silent actress of the teens, it might be Theda Bara.) Moreover, when Cameron resorts to Griffith-like crosscutting to build momentum, he’s hamstrung by his wide-screen format, which is less amenable to fast cutting than the screen ratio Griffith had to work with, and by the wealth of visual details (such as crowds and fixtures) he has to coordinate; even Cameron’s 1989 The Abyss, which worked with a simpler game plan, has better suspense sequences than this movie.

But in terms of narrative streamlining and moral simplicity, Titanic is still a lot closer to Griffith and his era than it is to other 90s disaster films. The characterizations of heroes and villains, which appear to be drawn with the utmost sincerity, all seem cut from the same Victorian cloth as those in Griffith’s melodramas — among others, there’s the dreamy and selfless Irish-American artist-adventurer, the tempestuous and freethinking Philadelphia debutante, the snarling and brutal zillionaire fiance (with an improbable touch of Brando’s Stanley Kowalski), and the fiance’s sadistic and preying valet (David Warner). For better and for worse, this is a movie that appears to believe in what it’s saying — and the lack of cynicism is refreshing.

“One of the more trying legacies left by those on the Titanic,” Lord notes in A Night to Remember, “has been a new standard of conduct for measuring the behavior of prominent people under stress” — a legacy that, ironically, can be found playing itself out in the pages of Time (where the rhetoric is no less moralistic than Cameron’s). Lord goes on, “It was easier in the old days…for the Titanic was also the last stand of wealth and society in the center of public affection. In 1912 there were no movie, radio or television stars; sports figures were still beyond the pale; and cafe society was completely unknown. The public depended on socially prominent people for all the vicarious glamour that enriches drab lives.” What tarnished that glamour, at least for subsequent generations, was the fact that, as Lord mentions earlier, “The night was a magnificent confirmation of ‘women and children first,’ yet somehow the loss rate was higher for Third Class children than First Class men.” Cameron’s Titanic is obviously a millennial statement of some sort, saying something about the present as well as the past, and the fact that he connects class with survival in both is entirely to his credit.

By beginning in the present — when the ruins of the Titanic, two and a half miles below the ocean’s surface, are being explored in search of a fabled (fictional) diamond — Cameron sets up a framework that suggests a kind of science fiction movie about the past, with 1912 made to seem as remote as 85 years in the future, and with the wrecked ship seeming as otherworldly as a wreck encountered in outer space. This same mood was beautifully captured in Stephen Low’s 94-minute Imax documentary Titanica (1991), which played in Chicago a couple of years ago — a film about the Canadian-American-Russian expedition that picked through the Titanic wreckage, at times suggesting an underwater 2001. Cameron’s movie begins like a sequel to that exploration, complete with probing spherical “pod” ships flanked by searchlights, and conjures up the same atmosphere.

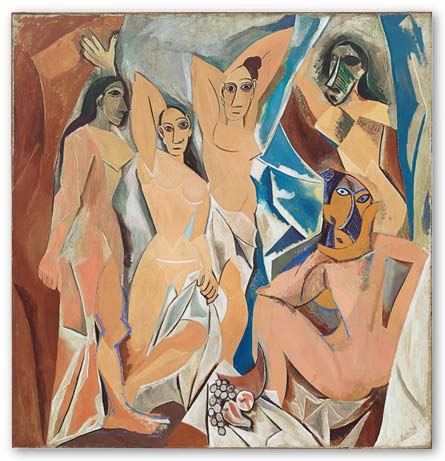

But once the original owner of the diamond, the 101-year-old Rose (Gloria Stuart, a Hollywood veteran best known for her work with John Ford, Busby Berkeley, and James Whale), enters the picture and proceeds to narrate the 1912 story in flashbacks, much of the eeriness in confronting the past is lost. For one thing, Cameron insists on having everyone speak 90s dialogue; he clearly doesn’t know how to make his characters speak 1912 dialogue without alienating the audience. And he makes the ludicrous decision to give the 1912 Rose a recently acquired collection of paintings ranging from Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon and one of Monet’s water lily canvases to familiar pieces by Degas and Cézanne, all of which presumably sank to the bottom of the ocean. Cameron can’t resist referencing works we know to show us how prescient Rose was, making her in effect the soul sister of Gertrude Stein. (She’s also hip to Freud, we learn in a scene that seems equally forced and improbable — though it also makes her seem progressive.) Still, a sense of awe about the mysteriousness of the past lingers, and the film’s poignancy would be severely curtailed without it.

Of course it’s one thing to evoke a sense of wonder about history and another to be historical — and I suspect this movie succeeds more with the former than with the latter. (At the second screening I attended, a Titanic survivor was in the audience, and I would love to hear her take on the matter.) Given the stark outlines and simple moralistic thrust of the story Cameron wants to recount, he understandably can’t find room to tell us that 65 minutes after the iceberg struck, the Titanic made the first SOS call in history. Prior to this, CQD was the traditional distress signal, but an international convention had just decided to substitute SOS — “easy for the rankest amateur to pick up,” Lord explains (in its own condensed legibility, Cameron’s movie is to Lord’s A Night to Remember what SOS is to CQD).

The movie also tells us nothing about chief baker Charles Joughlin, who spent his last two hours on the Titanic getting plastered on whiskey when he wasn’t throwing reluctant women into rescue boats and tossing 50 deck chairs overboard. When he finally entered the freezing water along with the ship’s stern, which was directly under his feet, Joughlin paddled around for two hours until a kitchen mate pulled him alongside an overturned boat. This might have served as a wonderful comic subplot, but not in the story Cameron’s telling.

Not even Lord bothers to tell us that one of the first-class passengers on the Titanic who perished was a famous author (and one of the favorite mystery writers of my youth), Jacques Futrelle, who wrote stories about a sleuth called the Thinking Machine — even though Mrs. Jacques Futrelle, who survived, is one of Lord’s acknowledged sources. My point is that anyone hoping to make something out of the sinking of the Titanic, fictional or nonfictional, has to have an agenda, and Cameron’s fictional agenda, despite its lack of shading, is clearly predicated on class divisions that actually existed and had real consequences in terms of who lived and who died. (Readers who don’t want part of the ending disclosed should check out here.)

Nouveau riche Texas millionaire Mrs. J.J. Brown — later immortalized as the Unsinkable Molly Brown, and deftly played in the film by Kathy Bates (though I wish Cameron had used her more) — is shown in the movie to be the only one in her rescue boat who wants to turn back and save more people, but according to Lord, two other women on the boat felt the same way and also pleaded in vain with the quartermaster. (Many of the rescue boats were far from full when they set off, and Cameron is as attentive to this fact as Lord.) According to Rose’s narration, “Fifteen hundred went into the sea; 20 boats floating by, and only one came back.” Only six, including Rose, were saved by this returning boat. According to Lord, “Of 1,600 people who went down on the Titanic, only 13 were picked up by the 18 boats that hovered nearby.” Either way, it’s a chilling percentage, and the film knows how to make the most of it. Rose’s narration continues, “Seven hundred people in boats had to wait: wait to live, wait to die, wait for an absolution that would never come.”

Given the religious overtones of this last phrase — reinforced when Rose adds a little later, speaking of Jack Dawson, “He saved me, in every way that a person can be saved” — it stands to reason that everything leading up to this grim conclusion would impart the same basic lesson. According to the press book, 32 percent of the Titanic’s passengers and crew survived, and out of this number 60 percent (199 people) were first-class passengers and 25 percent (125 people) were third class. (The press book also tailors its facts, excluding the second-class passengers, and where the crew fits into this arithmetic is anyone’s guess.)

Cameron is no Cecil B. De Mille — as spectacle the sinking of the Titanic lacks the power of the toppled temple in Samson and Delilah or the train wreck in The Greatest Show on Earth — and he’s at best a fledgling pupil of Kubrick and Spielberg when it comes to evoking vast spiritual reaches. But the ghostly, luminous images he creates of starlit boats with flashlights rowing through floating corpses are arguably worthy of Griffith in terms of beauty as well as conviction.

Maybe it’s true that, even short of its advertising costs and without allowing for inflation, Titanic the movie cost about 27 times as much as Titanic the ship, but figures don’t tell you everything. And maybe it’s true that the fictional Rose might have kept the fictional Jack alive by getting him out of the freezing water and sustaining him with some old-fashioned body warmth. I suspect that what keeps Jack freezing in the water is an old-fashioned view of courtly and self-sacrificing love that Cameron shares with Griffith (cf Broken Blossoms) — even if this doesn’t jibe too well with Rose and Jack having had sex (not “making out,” as the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane has it in a fit of Griffith-like prudery) earlier in a car inside the ship’s cargo hold. As a screenwriter Cameron clearly has plenty to learn. But Titanic is still one hell of a movie.