From the Chicago Reader (December 20, 1996). — J.R.

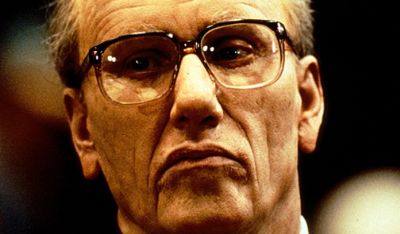

Ghosts of Mississippi

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Rob Reiner

Written by Lewis Colick

With Alec Baldwin, James Woods, Whoopi Goldberg, Diane Ladd, Bonnie Bartlett, Bill Cobbs, William H. Macy, Virginia Madsen, and Michael O’Keefe.

The Crucible

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nicholas Hytner

Written by Arthur Miller

With Daniel Day-Lewis, Winona Ryder, Paul Scofield, Joan Allen, Bruce Davison, Rob Campbell, Jeffrey Jones, Peter Vaughan, and Karron Graves.

“This story is true,” reads the opening title of Ghosts of Mississippi, a movie about the murder of NAACP activist Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi, in June 1963, and the conviction of his murderer, Byron De La Beckwith, which took a little more than 30 years.

“This play is not history in the sense in which the word is used by the academic historian,” Arthur Miller wrote in a note prefacing his 1953 play The Crucible, which depicts events that occurred in 1692, and which has now been turned into a movie adapted by Miller. Miller went on to detail the ways he’d changed history — he sometimes fused many people into one character, and he made a central character, Abigail, older. He went on to say that the characters should be taken as “creations of my own, drawn to the best of my ability in conformity with their known behavior, except as indicated in the commentary I have written for this text.” But, he added, “the fate of each character is exactly that of his historical model, and there is no one in the drama who did not play a similar — and in some cases exactly the same — role in history.”

For all the differences in these prefatory notes and in the stories that follow them, both movies are essentially making the same claim — that the gist of the events being shown is true. This means not that either film is accurate in every historical particular, but that what happens in both derives from an accurate assessment of what originally took place.

Like most viewers — including most reviewers — I have no special knowledge about either the murder of Evers and the conviction of Beckwith or the 1692 witchcraft trials held in Salem, Massachusetts. But like other viewers, I have plenty of feelings, notions, and biases about these events and how they pertain to the present. In the case of Ghosts of Mississippi, for instance, I’m especially grateful to the filmmakers for offering a full corrective to Mississippi Burning and A Time to Kill when it comes to representing everyday life in the deep south and to expressing some sense of civic responsibility in dealing with racist murders. These two virtues are closely connected; if one believes the lurid imaginings of Mississippi Burning and A Time to Kill about normal life in a typical southern town, then the vigilante form of justice celebrated in both those films begins to seem more viable.

The problem is that Ghosts of Mississippi, like The Crucible, is a liberal movie — anything but fashionable these days. Of course The Crucible wasn’t fashionable when it opened in 1953 either. In Robert Warshow’s thoughtful essay attacking it titled “The Liberal Conscience in The Crucible,” “liberal” is as much a dirty word (even though Warshow qualified as a cold-war liberal) as it is in today’s culture. (The essay was recently quoted without much thought by critics as disparate as the Village Voice‘s J. Hoberman and the New Yorker‘s Terrence Rafferty as justification for why we shouldn’t take the movie too seriously.)

Indeed, I can’t recall a single period when Miller’s liberalism has been deemed fashionable by the intellectual left in this country. Even when he defied the House Un-American Activities committee in 1956 by refusing to name names — leading to a conviction of contempt of Congress the following year that was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1958 — Miller was accused of having a martyr complex (like John Proctor, the hero of The Crucible) at least as often as he was praised or supported.

In fact, American intellectuals have always considered Miller something of a square, and the buzz I’ve been hearing from colleagues about Ghosts of Mississippi makes it sound similarly tainted. I’m not just bringing up these objections to dismiss them: though Ghosts of Mississippi is worthy of both praise and defense, it also has a colorless and cliched hero (a noble lawyer played by Alec Baldwin, complete with a conformist wife who leaves him when the going gets tough and a sympathetic, nurturing doctor who replaces her), and it depicts Medgar Evers’s widow (Whoopi Goldberg) as such a Goody Two-shoes that she doesn’t appear to age at all over the 30 years covered by the film. These are common problems for films that purport to represent people who are still alive — though James Woods’s performance as Beckwith and Bill Cobbs’s cameo as Charles Evers, Medgar’s older brother (a local disc jockey who refused to testify at any of the trials), are both so fine that they invalidate this criticism as an across-the-board principle. For that matter, just about all the secondary characters are handled with authenticity, humor, and grit, including some Jackson locals who reenact their own parts, and it is these individuals who are mainly responsible for the film’s rich texture.

Ghosts of Mississippi lacks the pizzazz that made Mississippi Burning and A Time to Kill commercial and their hokum acceptable to many viewers; it’s simple, corny, and decent, but not very exciting — unless you care about details of place and period or believe that long-term justice, the movie’s subject, matters more than the less serious short-term goals of those other movies. There are moments in Reiner’s film that brought tears to my eyes; the only tears I can imagine the other two movies provoking in me are tears of rage. But, hey, this is a square liberal movie, and provigilante sensationalism has always pulled in more customers, starting with The Birth of a Nation.

We like to read certain Russian and Eastern European dramas of the cold war as allegorical statements about government oppression, but we tend to be less alert to the handful of American works that made comparable allegorical protests. Johnny Guitar (1954) and Sweet Smell of Success (1957) remain popular cult items, but neither is commonly read as an allegory about the anticommunist witch-hunts. The Crucible, one of the few exceptions to this rule, is often castigated rather than praised for its political allegory, and in their recent objections to it, critics have been appropriating chunks from the Warshow essay without considering its historical context: (1) Communists, unlike witches, existed; therefore the Salem victims “were hanged because of a metaphysical error.” (2) “The Salem trials were not political and had nothing to do with civil rights.” (3) “Abigail Williams, one of the chief accusers in the trials, was about 11 years old in 1692; Miller makes her a young woman of 18 or 19 and invents an adulterous relation between her and John Proctor in order to motivate her denunciation of John and his wife Elizabeth.”

Some reviewers have dismissed The Crucible for more contemporary reasons. Siskel and Ebert recently agreed on their TV show that Miller’s play may have had relevance during the cold war, but it no longer does. And according to Rafferty, the “themes that come through most clearly” in the movie are “fear of women and hatred of youth.”

I’ll take each of these objections in turn. (1) Warshow’s literalism misses a crucial poetic truth — that a good many communists, fellow travelers, and liberals who refused to rat on their colleagues were destroyed because of a “metaphysical error” — the demonizing of them as serious threats to national security. Moreover, as Miller has recently pointed out, “In the 17th century…the existence of witches was never questioned by the loftiest minds in Europe and America.” (He added, “The irony is that klatches of Luciferians exist all over the country; there may be even more of them now than there are Communists.”)

(2) Warshow had a good deal more confidence than I do about what was or wasn’t political in the Salem trials. It’s also worth pondering his own political motive in 1953; seeing his objections to The Crucible in tandem with his rather sick essay about the Rosenbergs, published the same year, makes his cold-war politics look a lot more dubious today than Miller’s, even if he’s a better polemicist.

(3) Late last October, in an issue of the New Yorker, Miller referred to the real Abigail Williams [Winona Ryder in the film] as a teenager in 1692 — an assertion that has to be weighed against Warshow’s claim that she was “about 11” and Rafferty’s in the New Yorker this month that she was 11 and Proctor [Daniel Day-Lewis] was 60. Who’s telling the truth — and who, for that matter, is doing the New Yorker‘s fact checking? Even if Miller — who probably did more research than Warshow or Rafferty — is wrong, does this preclude the possibility of a sexual relationship or flirtation between her and Proctor? (Miller also reported in the New Yorker that his treatment of Proctor’s adultery with Abigail was informed by the dynamics of his own failing marriage at the time, which only adds to the uncertainty.)

Siskel and Ebert: The fact that we’re no longer in the midst of an anticommunist witch-hunt certainly doesn’t render the topic devoid of contemporary relevance. Americans don’t currently have kings as rulers; does this make Shakespeare irrelevant? Besides, insisting that The Crucible stand or fall only on the basis of its allegorical treatment of the witch-hunt rules out other fruitful parallels. To quote Miller’s recent article again, “For some, the play seems to be about the dilemma of relying on the testimony of small children accusing adults of sexual abuse, something I’d not have dreamed of 40 years ago. For others, it may simply be a fascination with the outbreak of paranoia that suffuses the play — the blind panic that, in our age, often seems to sit at the dim edges of consciousness.”

Rafferty: Even if one accepts his charges of misogyny and “hatred of youth” — and I find it difficult to dismiss them entirely — it’s surely blinkered to say that these nonliberal themes are the ones “that come through most clearly in the film.”

All these quibbles also fail to explain why the play has been produced repeatedly all over the world for 40-odd years. (Somehow I doubt that its impact in China and South America depends on its direct relevance to Joseph McCarthy or its alleged brief against teenage girls.) I’m not saying that this necessarily makes it good, but it does place the past and recent carping in a different perspective. And on the level of basic dramaturgy, I would argue, the play works, Miller’s adaptation successfully translates its most salient qualities to the screen, and Nicholas Hytner’s direction is taut and effective — especially in its use of Massachusetts locations and its wide-angle, deep-focus framing of period interiors, but also in its energetic performances. (I especially liked Paul Scofield as Judge Danforth.)

How do we deal with the hysteria of so many people who believed in the existence of witches? Carl Dreyer — who shot Day of Wrath in Nazi-occupied Denmark, though he set his witch trials almost 70 years earlier than Miller’s — scrupulously stuck to the terms of 1623, without introducing any 20th-century ironies. But that doesn’t mean that his film lacks a political meaning for 1943 — or 1996, for that matter. His proposition appears to be that witches do exist, and that the persecution and repression of women and female sexuality produces them.

This proposition isn’t as much at loggerheads with The Crucible as many commentators would have you believe — even if Miller’s story ends with the principled martyrdom of a man who refuses to name names. The virtue of this play and the film of this play is that many readings and meanings are possible. The same can’t be said for the propositions of its detractors, who merely want to sweep an enduring and potent form of liberal protest under the carpet.

A liberal protest against what? The hanging of witches or alleged witches. It must be comforting to assume this no longer happens.