From the Chicago Reader (January 22, 1999). For my earlier take on this film, written when it was released in London, go here. — J.R.

The Mother and the Whore

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Jean Eustache

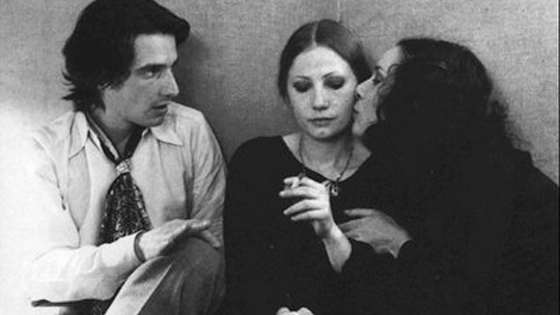

With Jean-Pierre Leaud, Francoise Lebrun, Bernadette Lafont, Isabelle Weingarten, Jacques Renard, Jean Douchet, and Jean-Noel Picq.

I have a friend who had a wonderful idea: he wanted to have his right hand amputated. Very seriously. Went to see a surgeon, said, ‘How much does it cost, I’m ready to pay.’ He wanted to have a porcelain hand made to replace it. And in his home, in a room, in the very center of the room, to place his real hand in formaldehyde, with a plaque reading, ‘My hand, 1940-1972’. And people would come to visit, like they’d go to an exhibit.

— Alexandre in The Mother and the Whore

Is it permissible to disapprove of a masterpiece? I find Jean Eustache’s obsessive, 215-minute black-and- white The Mother and the Whore, playing nine times this week at Facets Multimedia Center, every bit as mesmerizing today as I did when I attended the premiere at Cannes in 1973. I must have seen it four or five times since, the last time in the early 80s.

It’s a historical marker in a way that few other films are — not only the nail in the coffin of the French New Wave and one of the strongest statements about the aftermath of the failed French revolution of May 1968, but also a definitive expression of the closing in of Western culture after the end of the era generally known as the 60s. Yet what spooks me about seeing it today is that it looked like the tail end of something back in 1973 and even in the early 80s, but it registers in 1999 like something we’re still living inside — a Rip van Winkle slumber that’s lasted so long we’re all pretty well convinced that it must be reality. What is that something? A terminal collapse of will and hope and a mistrust of freedom that all too often passes for the human condition. The fact that the film’s writer-director committed suicide in his early 40s, in 1981, seems only to ratify the film’s bleak portrait not just of where we are today but of who we are. That portrait is so bleak I feel obliged to disapprove of, even to despise it. But its power over me is such that I can’t despise it without despising myself in the bargain. So I have to try to make some peace with it, try to come up with an honest account of what the film is saying to us in the 90s.

The movie recounts the activities over a few days of a dandyish French intellectual in his late 20s named Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Leaud), who’s living with and supported by his lover, Marie (Bernadette Lafont); she’s in her mid-30s and runs a small boutique. In the first scene he borrows a neighbor’s car and tracks down a former girlfriend, Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), who’s just started a new semester at the Sorbonne, and tries to persuade her to marry him, only to discover that she’s just agreed to marry someone else. (We and Alexandre briefly glimpse Gilberte with her husband, played by Eustache, toward the end of the film, in the liquor section of a department store.) After hanging out with an equally idle friend (Jacques Renard) at the Deux Magots cafe, Alexandre follows a young woman after she leaves a nearby table, asks for her phone number, and scores; the remainder of the film is devoted to his courting of her.

Her name is Veronika (Francoise Lebrun). She works as a hospital nurse, lives in a small room in the nurses’ quarters, goes to a lot of nightclubs, and is as compulsive about her promiscuity as Alexandre is about his idleness. She’s also compulsive about using the word “maximum” — a term that recurs as often as the phrase “pipe dream” in The Iceman Cometh, though the English subtitles in this newly translated version don’t do it justice — and about drinking. Alexandre is also a compulsive talker, and The Mother and the Whore has to be the ultimate filmic expression of a certain kind of French intellectual jabber — a film even more filled with talk than the works of Eric Rohmer, though in this case the talk isn’t so much circumlocution or exploration as a kind of narcissistic performance, the sort of activity Parisian culture regularly coaxes from its intellectuals. Most of this talk occurs in the Deux Magots and the nearly adjacent Flores; the prestige of these cafes is enhanced by a large newsstand and La Hune, an excellent bookshop specializing in art publications, that stand directly between them.

Alexandre’s courting of Veronika is carried out with Marie’s full knowledge; though he lies to her on occasion, he’s generally frank about his interest in other women. Still, he maintains a double standard, exhibiting rage whenever Marie plans to see a man she claims to have no sexual interest in but whom Alexandre perceives as a romantic rival. Eventually Alexandre, Marie, and Veronika make a couple of abortive stabs at sharing the same bed, until Marie rebels by attempting suicide. The film culminates in a long, tearful monologue from Veronika about the misery of loveless sex, then Alexandre accompanies her back to her room, where she rebuffs him with disgust, explaining that she may be pregnant with his child; he leaves, then runs back and proposes; she accepts, vomits into a basin, and Alexandre collapses on the floor against her refrigerator.

All the compulsive and obsessional behavior framed by the two marriage proposals relates to the film’s status as confessional art: the carefully scripted dialogue, according to the most authoritative accounts, was a compulsive effort to reproduce conversations that actually took place. Apparently everything Alexandre says and does in the film comes straight from Eustache’s life (though he isn’t a filmmaker), and Lebrun, who’d never acted in a film before, reenacts a part she played in life as Eustache’s lover. As Eustache described the project, “I wrote this script because I loved a woman who left me. I wanted her to act in a film I had written. I never had the occasion, during the years that we spent together, to have her act in my films, because at that time I didn’t make fiction films and it didn’t even occur to me that she could act. I wrote this film for her and for Leaud; if they had refused to play in it, I wouldn’t have written it.”

Though the film is devoted to reproducing real characters and events and lasts over three and a half hours, it isn’t an undisciplined or unselective ramble. Rigorously structured and shot in 16-millimeter that was blown up to 35, it deliberately aims for a documentary look while qualifying as a particular reading and interpretation of certain events; as Pauline Kael noted back in 1974, “It took three months of editing to make this film seem unedited.” Each sequence begins with a fade-in and ends with a fade-out, creating a ghostly overall texture that seems inseparable from the film’s complex relation to nostalgia.

This nostalgia comes in several layers, all of them tinged with irony. Perhaps the most important layer relates to the 40s: Alexandre’s unnamed friend has a fetish for Nazi paraphernalia, such as a book about the SS and a record of Zarah Leander songs, which prompts Alexandre to lament being born after the time when girls swooned over soldiers (“The prestige of the uniform,” he sighs). The same friend capriciously steals someone’s wheelchair (“probably a paralytic”) with all the amused amorality of a Gestapo thug; and a climactic shot focuses on a bereft Marie as she listens to a lovely Edith Piaf song, “Les amants de Paris,” recorded in 1948.

Then there’s a more ambiguous kind of nostalgia tied to the New Wave and its aftermath, evoked by the naturally lit black-and-white cinematography and the casting of Leaud, Lafont, and even Weingarten (whom Robert Bresson introduced in his 1972 feature Four Nights of a Dreamer, in which she also rejects the hero for another man). Finally, and still more ambiguously, there’s an implied nostalgia for the dreams of May 1968 that curiously links them to memories of the Nazi occupation. When Alexandre reproaches Gilberte for forgetting their love and resigning herself to “mediocrity,” he says, “After crises one must forget everything quickly. Erase everything. Like France after the occupation, like France after May ’68. You recover like France after May ’68.” And in subsequent evocations of that time he says, “There was the Cultural Revolution, May ’68, the Rolling Stones, long hair, the Black Panthers, the Palestinians, the underground. And for the past two or three years, nothing anymore.” Later, “In May ’68 a whole cafe was crying. It was beautiful. A tear-gas bomb had exploded…a crack in reality opened up.”

One can’t claim that the dreams of May ’68 and those of the North American counterculture were identical. Hallucinogenic drugs play no role in the lives of Eustache’s characters, perhaps because French Catholicism had already had a long tradition of linking drugs and rebellion, as found in the work of writers like Baudelaire. And the impact of feminism on French life was so slight in 1973 — and remains slight in 1999 — that Alexandre can blithely reduce women’s lib to the issue of whether a wife should serve her husband breakfast in bed. In more ways than one, Catholic notions about gender and procreation are too operative in The Mother and the Whore — just look at the film’s title — for feminist alternatives to do anything more than occasionally graze the consciousness of the characters. (If you want a triumphantly feminist and in other respects much more positive closure to the New Wave, I warmly recommend Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating, which was made shortly before Eustache’s epic and is finally available here on video — a film in which patriarchal power exists not only to be challenged but ultimately to be joyously toppled. But though Rivette’s film enjoyed some commercial success when it came out in Paris, it had no status whatsoever as a statement about the zeitgeist; perhaps because it was expressed in terms of fantasy, no one at the time took it as a reflection of any social reality.)

So in some respects it might be argued that France’s version of the counterculture and what it eventually produced was a few steps behind what was happening in North America — and maybe even more than a few steps when it comes to women’s rights. However, French student radicals came much closer to joining forces with workers and immobilizing their government than their stateside counterparts ever did. And for better and for worse, Parisian culture’s response to casual sex and living arrangements like that of Alexandre and Marie places the ethical choices of these characters in a somewhat different realm from those made by hippies in Haight-Ashbury. I was living in Paris when the film was shot and first released. My closest friend there was a sculptor and draft dodger from Watts who was supported by the older French woman he lived with, and he cheated on her even more than Alexandre cheats on Marie. However much one might disapprove of this sort of arrangement, it was tolerated and even sanctioned by Parisian culture in much the same way that the intellectual jabber was — less encumbered by puritanism and feminism and ultimately protected by a profound belief in pleasure motored by male entitlement.

Despite these differences, the behavior and illusions of Alexandre, Marie, and Veronika are so thoroughly unpacked that they become universal expressions of how men and women were trying to relate to one another in the early 70s, at least in the Western world. (One reference to this analysis is the book Alexandre is seen reading and carrying around in a few early scenes, The Captive, the fifth and in some ways darkest volume of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past.) If the abject failure of the experiments undertaken by all three characters constitutes much of what seems defeatist and masochistic about both the film and the zeitgeist it announced — the era of hopelessness about social change and human possibility we’re still living through — Eustache is intelligent and poetic enough to show us these people in the round, and even to allow us to propose solutions to their problems that are different from their own. Yet I can’t say that he encourages us to do this. In the final analysis, The Mother and the Whore is in love with the idea of defeat; that is its reactionary strength, and most of what I cherish as well as mistrust about the film derives from this fact.

From a mainstream point of view, Eustache was a minor figure of the French New Wave who somehow managed to make one major feature. I recall this was the position of critic Andrew Sarris when we discussed the film shortly after its premiere, and it has been my tentative position as well. But it is not a position generally shared by younger critics who have managed to see Eustache’s other work; many of them consider him a major figure, and some even prefer different works, including his subsequent feature, Mes petites amoureuses (1974), an autobiographical film about his childhood in a small town. Many of these critics link Eustache to John Cassavetes, Philippe Garrel, and Maurice Pialat — three other highly personal, confessional, and gifted filmmakers who work in a mode that might be described as touchy-feely in that they smack of encounter groups and a hunger for emotional catharsis. My own generation, however, links Eustache more with Rivette (with whom Eustache worked as editor on a French TV series about Jean Renoir), Eric Rohmer, Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard (who furnished Eustache with leftover film stock from Masculine-Feminine in the mid-60s, enabling him to make Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes), and Luc Moullet (who coproduced Eustache’s Le cochon with Francoise Lebrun). The difference between these two traditions isn’t merely academic; though Eustache can obviously be seen as a filmmaker who straddles both, where one decides to place him has a great deal to do with how one ultimately interprets and judges his work, historically as well as ideologically.

I’ve seen six of Eustache’s dozen films, all of them made between 1963 and 1980: the 47-minute, autobiographical Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes (1966), also starring Leaud (and the only other Eustache film, to my knowledge, that has ever been distributed in the U.S.); Le cochon (1970), a 50-minute documentary about the slaughter and dismemberment of a pig by farmers; The Mother and the Whore; Mes petites amoureuses; Une sale histoire (1977), an odd experiment consisting of a 16-millimeter documentary of Jean-Noel Picq telling four women (including Lebrun) a scabrous anecdote about peeking through a hole into a ladies’ room in a cafe and a 35-millimeter “remake” of this documentary with actors (including Michael Lonsdale as the storyteller); and Les photos d’Alix (1980), an 18-minute experimental documentary. The fact that even the “fictional” films in this list are based on some form of actuality combined with the fact that Mes petites amoureuses is Eustache’s only standard-length feature (at 123 minutes) helps explain what has kept most of his work marginal even in France. It’s been well over 30 years since I’ve seen Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes, so I don’t feel I can assess it today. But it clearly was an important reference point for Eustache when he made The Mother and the Whore; when Alexandre alludes at one point to having once dressed up as Santa Claus, it’s Eustache’s way of linking Leaud’s roles in the two films.

The casting of Leaud, Lafont, and Lebrun in The Mother and the Whore has some bearing on how different generations are apt to read this film. The first two actors were early Truffaut discoveries who helped launch the New Wave — Lafont starring in Truffaut’s first major short, The Mischief Makers (1958), and Leaud starring in his first feature, The 400 Blows (1959) — and those of us who grew up with these actors and saw most of their major films in sequential order find it difficult to separate Marie and Alexandre from the cumulative iconography of these earlier parts, even if Eustache puts a different spin on their personas. This iconography isn’t likely to matter as much to younger viewers who saw these films in scrambled order.

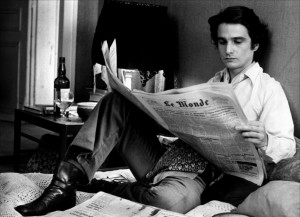

Indeed, Leaud is as central to the New Wave as John Wayne is to the western, from The 400 Blows, Love at Twenty (1962), Masculine-Feminine (1966), Made in USA and La chinoise (1967) to Stolen Kisses and Le gai savoir (1968), Bed and Board (1970), Two English Girls (1971), and even Last Tango in Paris (1972), where his quasi-parodic recapitulation of his previous parts struck some viewers as overkill. Despite all the variations in his characters, he conjured up a sensitive, neurotically frantic, and yearning romantic youth scrambling for acceptance and, with few exceptions (e.g., the middle-class assimilation of Bed and Board), never quite achieving it. Then, shortly before The Mother and the Whore, his persona began to take on signs of frenetic paranoia and extreme isolation, suggesting a form of impending madness, especially in Moullet’s 1970 Une aventure de Billy le Kid (A Girl Is a Gun) and both versions of Rivette’s Out 1 (1971 and 1972), and to a lesser degree in Truffaut’s Day for Night (1973). Within this overall development, Alexandre represents the moment when this persona finally achieves its apotheosis — Saint Narcissus of the New Wave, a beloved insider at last — and then begins to come apart, revealing his exalted state is only a desperate self-construction.

If Alexandre and Colin in Out 1 represent the high point of Leaud’s career to date — these two characters comprising his richest and most troubled performances — this is because they combine and then reverse the vectors of all his previous New Wave parts. (This deconstruction is partially echoed by subtle but radical shifts in the film’s narrative viewpoint. Our last look at Marie, when she’s listening to Piaf, is the first time the film shows us something Alexandre doesn’t see, and a brief moment with Veronika alone in her room shortly afterward is the second. The moment Alexandre loses his omnipotence as implicit narrator, he loses part of his status as hero as well.) If Leaud seems to understand Alexandre down to his very bones, perhaps it’s because he was supported and nurtured by the same cultural matrix that yielded his and Eustache’s fictional counterpart, who winds up brutalizing the two women who care about him the most.

Lafont’s Marie entails a comparable and compatible reversal. The sassy working-class woman who typically never took shit from anyone in her early films for Chabrol (Le beau Serge, Leda, Les bonnes femmes, Les godelureaux), the spitefully avenging heroine in Nelly Kaplan’s feminist comedy A Very Curious Girl, and the unrepentant murderer who hoodwinks a dim sociologist in Truffaut’s Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me finally winds up an exploited and victimized older woman in The Mother and the Whore. She’s still angry and spiteful, but Eustache places her, like Alexandre, at the end of a long road where she seemingly has nowhere left to turn. (The film is dedicated to her real-life counterpart, who wound up killing herself.)

In partial contrast to these icons, Lebrun winds up embodying the scarred soul of the film, becoming its main documentary element, free of the cumulative associations of 15 years of New Wave filmmaking and therefore able to forge a somewhat fresher image of damnation and doom. She’s as good a reason as any to see the film — her character’s climactic monologue is the emotional high point, and her authentic outburst after Alexandre flippantly disparages every possible form of political engagement or emotional commitment is the film’s only measure of truth. Her torrent of self-pity may not amount to much — and neither does ours, but given our pessimism about the imperfections of human nature, which easily slides into an alibi for inertia, it’s the best we can come up with in the 90s. And it’s certainly to the credit of this searing masterpiece that it makes us care deeply about what we’ve lost.