From Filmmaker, Fall 1993 (vol. 2, #1). – J.R.

One reason why quieter, less obviously trendy North American festivals like those in Denver, Honolulu, and Vancouver attract me more as a critic than the hit-making events held in Sundance and Telluride is that they offer a genuine alternative to the feeding frenzies that accompany most current movie launchings — an atmosphere conducive to looking at movies without the usual starstruck distractions . By the same token, one advantage of Locarno over bigger and better publicized competitive European festivals like Cannes, Berlin and Venice is that it takes place in a more relaxed ambience, a space to think in.

Held in a lakeside resort town in the Italian speaking part of Switzerland in early August, where nightly outdoor screenings in the Grand Piazza for up to 7,000 spectators are the main public events, the festival also boasts exhaustive retrospectives, a Critics Week devoted to documentaries, an annual assortment of films about film, and many other sidebars and special events. One of the many specialty items this year was a series of clever, elaborate commercials for Bris Soap made by Ingmar Bergman in the early 50s. Another was the screening in the Grand Piazza of Forty Guns (1957) -– Sam Fuller’s delirious avant-garde western, shot in only ten days – to honor Fuller himself, the festival’s guest of honor, robustly celebrating his 82nd birthday.

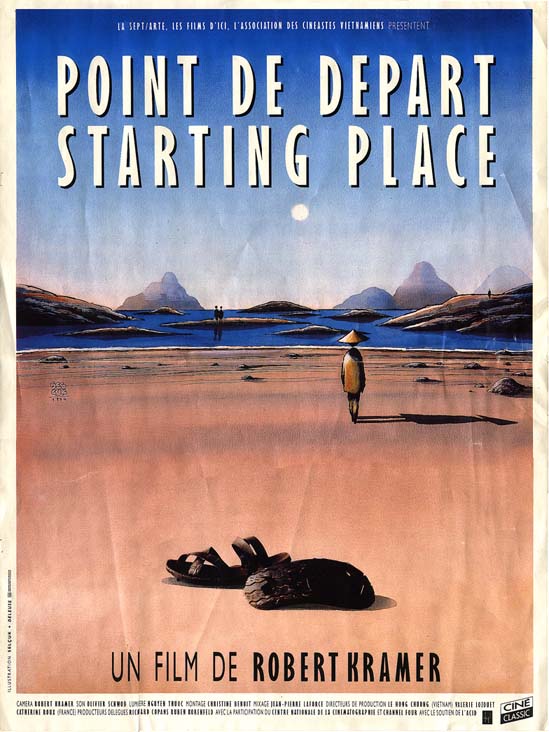

Under the new and informed directorship of Marco Müller, who started last year, the festival has been making a special effort to show world premieres of films by relatively new directors in competition -– a strategy that often tends to make these selections less exciting than many of the others. In fact, my two favorite films at Locarno this year, Chantal Akerman’s D’est and Robert Kramer’s Starting Place, were both shown out of competition -– the first as a special event, the second in the Critics Week. Both are very contemporary personal essays that invite and reward a certain amount of reflection, which made their appearance in Locarno especially welcome.

Akerman’s highly formal feature, one of her toughest and most severe (as well as gloomiest) stems from a trip taken over several months (from late summer through mid-winter) from East Germany to Moscow, and largely consists of tracking shots past landscapes and people. Akerman’s powerful painterly sense, which seems to be perpetually looking for Edward Hopper in Eastern Europe, combines with a feeling for intimate detail that allows these locations and faces to seep into our very bones.

If the absence of any narration or commentary in D’est seems central to the film’s overall effect, Kramer’s own highly personal narration to Starting Place — chronicling his return to Vietnam 23 years after he shot The People’s War in Hanoi — is equally crucial. Beautifully and evocatively edited with a grace that recalls Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, this is a thoughtful, provocative, and moving engagement with a subject that still represents an enforced blank spot in this country’s consciousness — a void only made more obvious, I should add, by such ersatz “Vietnam” movies as Casualties of War and Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. A 60s American radical who has been based in Paris since the 70s, Kramer, unlike most of his compatriots, has managed to maintain a complex, multifaceted continuity with his earlier concerns, and for this reason alone, I hope some U.S. distributor will pick this film up; within the present climate, it has the force of a revelation.

Among the three American independent features shown in competition, I warmed most readily to Sara Driver’s When Pigs Fly — by all counts the least fashionable of the trio (the others were Beth B’s Two Small Bodies and Rick Linklater’s Dazed and Confused) in terms of ambition (modest) and delivery (slow), but the one that left me with the most residue.

As sweet and as goofy as Driver’s earlier Sleepwalk, but with a much more legible plot, this ghost comedy with a rather English sense of character focuses on an inactive and nearly narcoleptic jazz musician named Marty (Alfred Molina) in an industrial port town who gradually gets roused out of his stupor by two ghosts: a woman (Marianne Faithful) and a little girl (Rachel Bella). As a story, the movie remains determinedly slight, and at times the whimsical reminders of Topper (one of Driver’s avowed models) come too close for comfort; but the poetry of the people and place leaves a bracing aftertaste.

Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, which gives us 18 hours in the lives of several 1976 teenagers just after their spring semester ends, is a semiplotless chronicle of boredom, cruelty, and drift that interestingly bears more than a passing resemblance to Zhang Yuan’s independent mainland Chinese feature Beijing Bastards, which was also shown in competition. While sound arguments could be made for Dazed and Confused as satire and for Beijing Bastards as a free-form evocation of Beijing’s punk scene, both movies seem letdowns after the more adventurous and more tightly budgeted independent features that preceded them — Linklater’s Slacker and Zhang’s Mama. Prevailing wisdom to the contrary, it seems that if you throw more money at no-budget independents, the work that emerges is not necessarily going to be bigger and better; it may simply look more like everything else in the homogeneous mainstream.