From the Chicago Reader (August 9, 1991). — J.R.

MY FATHER’S GLORY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Yves Robert

Written by Jerome Tonnere, Louis Nucera, and Robert

With Philippe Caubere, Nathalie Roussel, Didier Pain, Julien Ciamaca, Therese Liotard, and Victorien Delmare.

Though I’ve had only limited acquaintance with Marcel Pagnol’s work as a filmmaker, it’s clear to me that he was an important if neglected figure in French independent cinema. He was not only a forerunner of the Italian neorealists and a playwright-turned-filmmaker who set up his own studio in Marseilles in 1933, but also an unusually devoted director of actors. He liked to film his favorites — people like Raimu, Fernandel, Alida Rouffe, and Pierre Fresnay — in static camera setups with lots of dialogue, theoretically ending a shot only when he ran out of film. It may seem a limited aesthetic, but for passionate proactor directors like Jean Renoir (whose 1934 Toni was produced by Pagnol) and Orson Welles it carried the force of a revelation, and the sunny Provencal settings provided a relaxed airiness and earthiness to the extended talk fests.

Pagnol’s output as a writer has become fashionable again, thanks to the popularity of Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring — both based on Pagnol novels and directed by Claude Berri. Regrettably, Pagnol’s special qualities as a filmmaker are still being overlooked — and I’m not even sure that his most distinctive qualities as a writer are highlighted in the Berri films. Jean de Florette and its sequel are cutesy forays into French academic filmmaking and hammy salt-of-the-earth philosophizing informed by a relish for rustic malice. By contrast, a Pagnol play like Topaze (which I know only through Harry D’Arrast’s exquisite American movie with John Barrymore) is characterized by gentleness and sadness — it’s a far cry from the melodramatic revenge-plot mechanics of the Berri films.

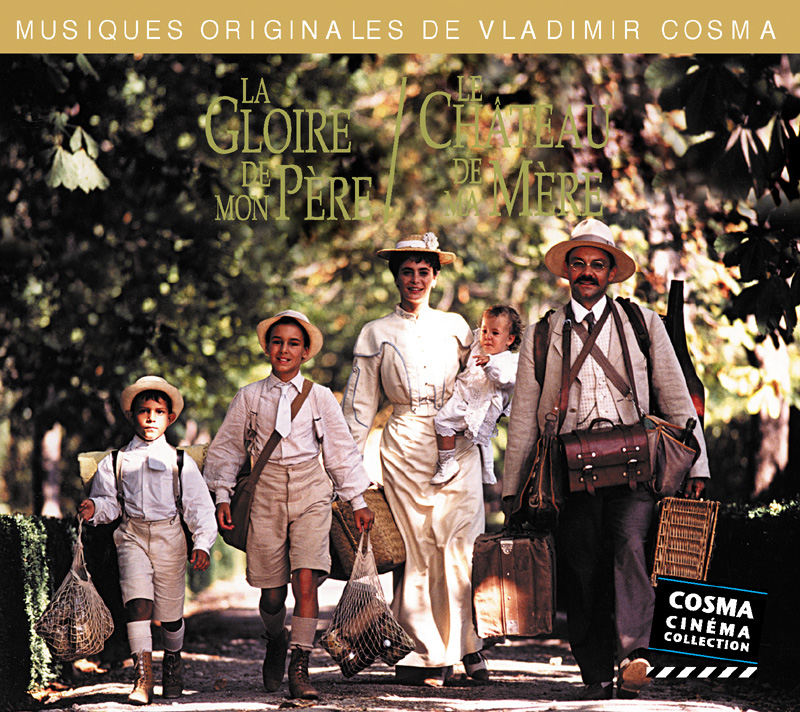

Consequently, I didn’t expect to like Yves Robert’s My Father’s Glory, an adaptation of the first volume of Pagnol’s memoirs. (A sequel, My Mother’s Castle, is scheduled to appear shortly.) I anticipated a straight commercial spin-off of the Berri features. While Robert has staged several Pagnol plays, he’s known in this country mainly as the director of boulevard farces — The Tall Blond Man With One Black Shoe (1972), Pardon mon affaire (1977), and both films’ sequels. On the evidence of My Father’s Glory, he’s almost as much of an academician as Berri and is just as far from the unbuttoned sprawl of Pagnol’s actorly brand of filmmaking (there are times, in fact, when the actors’ movements seem overrehearsed). But this doesn’t prevent his film from having a charm and evocativeness of its own, both of which can be found in the material, the settings, the decision not to use scenery-chewing stars, the Provencal accents, and the sentimental but effective sweep of Vladimir Cosma’s lush score.

Pagnol (speaking in the voice of the adult Jean-Pierre Darras) begins by recounting his own birth in 1895, rather like Tristram Shandy, then starts off the commentary with a metaphysical paradox: “My father was 25 years older than me and always remained that way. But my mother and I were the same age because my mother was me, and I thought as a child that we were born together.” His father, Joseph (Philippe Caubere), is a schoolteacher in Aubagne whose classes are held next door to his house; Marcel is often deposited in the classroom when his mother Augustine (Nathalie Roussel) has to go out, and he causes a certain amount of consternation when he reveals at the age of five that he’s able to read a sentence off the blackboard.

In a way, the whole progress of Marcel’s development as it’s casually charted in the film is from simple solipsism to thoughts and feelings in which the outside world matters more and more, in which other members of his family and his physical surroundings play an increasing role. The family moves to Marseilles when Joseph gets promoted, Augustine’s sister Rose (Therese Liotard) meets and marries a portly fellow named Jules (Didier Pain), and Augustine gives birth to another son and then a daughter.

All this comprises roughly the first half of the movie and the first 11 years of Marcel’s life; the remainder is devoted to a single summer holiday — “the happiest days of my life” — at a rented villa near a remote village in the hills called La Treille, where all seven members of the family go. Marcel befriends a poor boy from the village named Lili (Joris Molinas), but most of the drama that’s reflected in the retrospective narration hinges on Marcel’s troubled identification with his father; he fears his father will be regarded disparagingly by the villagers and will be outclassed by his Uncle Jules in such rural activities as hunting.

Interestingly enough, the interactions of the family during the two lengthy sequences that conclude the summer holiday — when Marcel becomes fixated on the idea of accompanying Joseph and Jules on a daylong hunting trip, and when he plots to run away and live in a cave rather than return to the city — depend largely on subtle and calculated forms of reticence, particularly on the part of the adults. The net effect is to suggest that Marcel’s life virtually begins in language (as he retrospectively narrates his own birth and charts his precocious reading habits), but that his true education begins when he starts to understand and appreciate what his parents’ silences mean. (In one sense, of course, these silences constitute another kind of language, and the film takes care to show us that Marcel is reading Robinson Crusoe in La Treille — so perhaps it would be more accurate to say the development is from oral recitation to more grown-up forms of silent reading.)

Part of the enchantment of My Father’s Glory is the language (lines in the narration like “The Rs rolled off his tongue like a river along its bed”) as well as the absence of language (such as the sounds of cicadas in the hills around La Treille). Another part of it is the period ambience and nostalgia. As Serge Toubiana writes in Cahiers du Cinema, “Pagnol describes a France in all its simplicity — before mass media, before modern times. There is no menace. It’s the opposite of what people see today in their lives: drugs, AIDS, violence. It’s the inviolable myth of France, the family, the children; Pagnol is harmony and unity.”

Sentimental, old-fashioned stuff to be sure — but the simplicity and physicality of Robert’s film is effective mainly because it serves to put across this questionable vision. (Only a selective censorship and simplification of the past — such as that represented by Main Street, USA, in Disneyland, where every brick and shingle and gas lamp is five-eighths the original size to make it more toylike and containable — can make it wholly unproblematical and simple in relationship to the present.) This vision harks back to a feeling of affection and tenderness toward the past and what might be called a “faith in the image” that used to be commonplace in many of the most routine American kitsch movies of the 40s and 50s — not the authentic classics like The Magnificent Ambersons and Meet Me in St. Louis but sillier movies like Cheaper by the Dozen, Centennial Summer, On Moonlight Bay, Summer Holiday, and Take Me Out to the Ball Game, among many others.

Seeing My Father’s Glory only a few days after seeing such current MTV-style “nostalgia trips” as Mobsters and the forthcoming Barton Fink, I was deeply saddened to think that such routinely reverent examples of period evocation as my 40s and 50s examples may no longer be possible in American movies, simply because not enough of the past is available to us anymore — and because no amount of money and production design can bring it back to us if we no longer remember it clearly. Believing more in effects than in images, more in limited currency than in endurance, our movies about the past can summon up only postmodernist patchworks, jumbled and unfixed impressions modeled on scrambled foreshortenings, naive anachronisms, and slender conceits that are finally about as evocative of the past as TV commercials. Faced with such trendy flatness, I find the allure of a European film that can still summon up the past with some assurance hard to resist.