From the Chicago Reader (June 30, 1995). — J.R.

Pocahontas

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg

Written by Carl Binder, Susannah Grant, and Pillip LaZebnick

With the voices of Irene Bedard, Judy Kuhn, Mel Gibson, David Ogden Stiers, Linda Hunt, Russel Means, Christian Bale, Billy Connolly, and Joe Baker.

American history without Smith and Pocahontas is hard to imagine. If the void were there, something else — yet something similar — would have to fill it. — Bradford Smith, Captain John Smith: His Life & Legend

I assume we’re still some years away from the abolition of state-supported schools and the gleeful handing over of our entire system of education to the Disney people. But some of the studio’s clever promotions for Pocahontas might make you conclude that some such changes have already taken place.

Consider the “special collector’s issue” of the kids’ magazine Disney Adventures devoted to “Pocahontas: The Movie, The Stars, The Real-Life Story,” complete with ads for some of the spin-off products. It afforded me almost as much food for thought as the two hours I spent in a library reading through historical accounts of what “really” happened in the wilds of Virginia in the early 17th century. The little magazine also plied me with facts, but interpreted them rather differently. Here’s Christine Donnelly in “The Powhatan Way”: “Most of what we know about the Powhatans comes from the Englishmen who colonized Jamestown at the turn of the 17th century. From their accounts, the Powhatans were athletic, liked to eat and sported cool haircuts and tattoos. Kinda sounds like us!”

Of course the romance Disney creates between Pocahontas and John Smith is pure fabrication, but even the details in the movie are often scramblings and distortions of historical records whose truth is itself disputed. The “serious” young Indian Pocahontas’s pop wants her to marry — who winds up getting killed by Thomas, a young protege of John Smith — is named Kocoum. And according to the contemporary account of one William Strachey, Pocahontas was married to an Indian named Kocoum (apparently after Smith returned to England, in 1609, and before she married Englishman John Rolfe, in 1614). “Thomas,” it turns out, is also the name of the son Pocahontas had with John Rolfe in 1615. (She sailed with him to London the following year. There she met the dramatist Ben Jonson — who wrote about her eight years later in his comedy The Staple of News — and attended a court masque he prepared, at which the king and queen were present. Two months later, on her way back to the New World, she became sick, returned to England, and died of unknown causes. Some accounts say it was of a “broken heart,” but if so, it’s hard to trace her heartbreak to Smith; a likelier explanation would be her separation from her family and tribe.)

Whether Pocahontas actually saved John Smith’s life in 1608 is still disputed. Smith failed to mention any such incident in his book A True Relation of…Virginia, written the same year. (The book does mention Pocahontas, but only as a ten-year-old child sent as an ambassador to the white settlement by her father, Chief Powhatan, at some point after Smith’s captivity.) It was apparently only in 1616 that Smith recounted the 1608 life-saving incident, in a letter written to the queen of England that remains the only piece of evidence that the event actually occurred. According to this account, Pocahontas argued to her father that Smith be kept alive but in captivity so that he could manufacture bells and beads for her (a detail understandably omitted in the Disney version). Smith’s delay in telling the story led Henry Adams to conclude that he made it up, but other commentators have pointed out that Smith had nothing to gain by telling the story in 1616, and plenty of reason in 1608 to keep quiet in an all-male settlement about a little girl saving his life.

The most plausible theory seems to be that of John Gould Fletcher, who explains in his 1928 book, John Smith — Also Pocahontas, that such acts of salvation were part of Indian culture. He cites in particular how the life of Spanish explorer Juan Ortiz was saved in the early 16th century when the chief’s daughter intervened in a manner very similar to Pocahontas. Powhatan may even have instructed Pocahontas to do exactly what she did, Fletcher suggests, for political reasons: perhaps he had his own motives for saving Smith’s life, and could deflect the censure of his tribe for this act of mercy by blaming his daughter; the “bells and beads” might have been just part of the cover story.

But whether the incident really occurred is ultimately less important than our wish to believe that it did. The genocide of Native Americans perpetrated by Europeans was and clearly still is in need of some sort of myth to humanize killers and victims alike. In his recent The Conquest of America, Tzvetan Todorov estimates that between 1500 and 1550 the population of the Americas was reduced from about 80 million to 10 million. If we consider that the world population in 1500 was roughly 400 million, this means that somewhere between a fifth and a sixth of the planet’s human population was wiped out during those 50 years. In Mexico alone, in the years between Cortes’s invasion in 1519 and 1600, the population was reduced from 25 million to 1 million. These staggering figures, the immensity of the holocaust, help explain the vast appeal of a story about an Indian girl throwing herself protectively over the body of a conquering Englishman more than twice her age: it makes both of them seem like human beings.

For all the noble (as well as mercenary) intentions behind Disney’s Pocahontas, there’s a certain blandness at its center that interracial romance, multiculturalism, pacifism, and pantheism can’t shake off. If all Disney cartoons are to some extent “art” by committee, this one qualifies to a greater extent than many others.

Pocahontas and Smith are sexier than most Disney cartoon characters, but their distance from their historical counterparts remains troubling. Preaching tolerance is a halfhearted enterprise if accuracy is barely heeded. (According to Bradford Smith, quoted at the beginning of this review, when Pocahontas saved Smith’s life she “was just past the age when Indian girls went about naked with only a bit of moss at their thighs. Her costume for this historic event consisted of a leather apron and perhaps a few beads.” Yet in the movie she and Smith appear to be the same age.)

And much as I regret saying this, the more racist Disney cartoon features (like Dumbo and Aladdin) tend to have greater personality and energy than the less racist ones, perhaps because they have a deeper mythological resonance. In The Return of the Vanishing American, critic Leslie A. Fiedler remarks that many of the sentimental literary and dramatic adaptations of this story make Pocahontas lighter-skinned than her “evil papa” — a kind of mythical emphasis I’m happy to report this Pocahontas omits, though such an omission makes the story less melodramatic. (Those preferring racist melodrama can readily find it in the Pocahontas pop-up book or in one of the other new Disney Pocahontas books available, which clearly make the father darker than the daughter, while some make Kocoum darker than she is.)

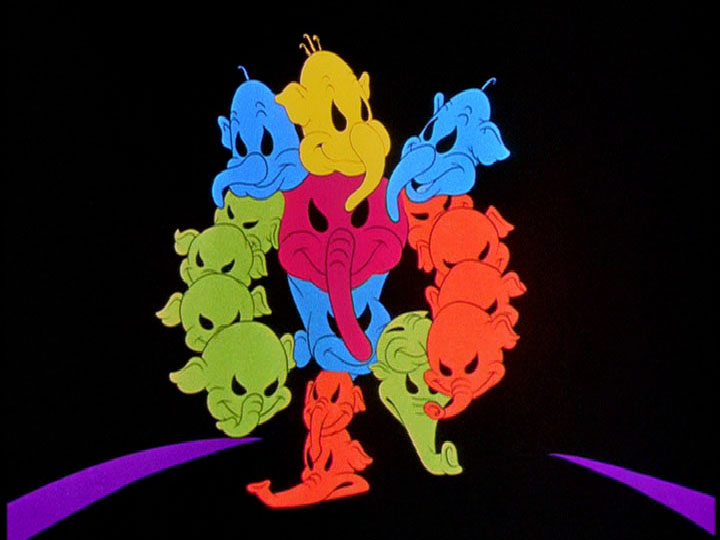

The movie may also lack energy because the easy transformations of landscapes and settings typical of Disney animated features no longer carry the same dreamlike or dramatic charge. (Consider how intoxicating “The Dance of the Pink Elephants” must have been when Dumbo first came out, over half a century ago.) Thanks to the pervasive influence of music videos, when Governor Ratcliffe (a standard Disney gay villain) shifts suddenly from a production number on the muddy Virginia coast to an appearance in a gold costume in an outsize Cinderella palace, it seems merely business as usual, not a wondrous form of magic. By the same token, most of the wit in Pocahontas derives from animated approximations of tried-and-true gags; when Grandmother Willow Tree wisecracks, “My bark is worse than my bite,” the reaction shot in which one weary owl dubiously eyes another is a veritable model of TV sitcom.

Though this movie struggles to be politically correct, mainly by juxtaposing greedy Englishmen with nature-loving Native Americans, that effort founders on the film’s handling of language, and virtually from the outset — clarifying how central such Eurocentric manipulations have always been to our westerns and third-world adventure films. The first time we encounter Pocahontas, even before she meets Smith, for instance, she’s speaking like a Valley girl. The filmmakers try to suggest that the Indians speak something other than English by inserting a few Native American words, then have them switch back to English, a process yielding a slew of ungainly non sequiturs when Smith and Pocahontas converse the first time. (Miraculously, they find they can communicate perfectly within a matter of seconds, but since Powhatan, Grandmother Willow, and the other Native Americans already speak English, the fact that the couple have any trouble at all is weirdly illogical.)

As usually happens in Disney cartoons, the filmmakers seem more at home with animals than with humans, especially in this case because the animals don’t have to communicate in spoken language at all. The three central exhibits are Ratcliffe’s pampered English bulldog and a raccoon and hummingbird, Pocahontas’s mascots. Repeatedly cutting away from the human leads, treated (often stiffly) as Romeo and Juliet, to the low-comedy animal antics, the writers and animators seem to breathe easier, basking in comic relief — and the relief is frequently ours as well. Though some version of class warfare is clearly played out in the confrontations between the poor raccoon and the wealthy canine — ghetto rodent versus top dog (or is it slum landlord?) — racial and cultural differences are not at stake in the obvious fashion they are in the rest of the film, and the moviemakers find it easier to relax and play around without them.