From the Chicago Reader (April 28, 1989). — J.R.

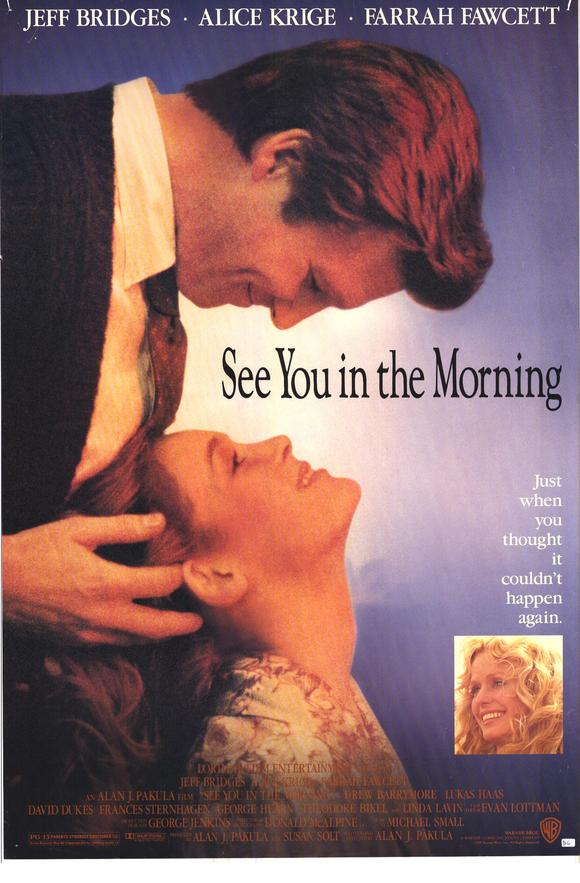

SEE YOU IN THE MORNING

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Alan J. Pakula

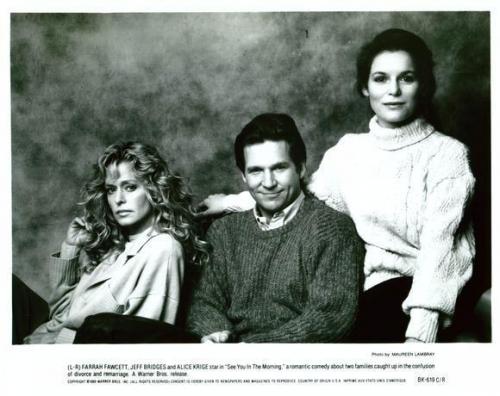

With Jeff Bridges, Alice Krige, Farrah Fawcett, Drew Barrymore, Lukas Haas, David Dukes, Frances Sternhagen, George Hearn, Theodore Bikel, and Linda Lavin.

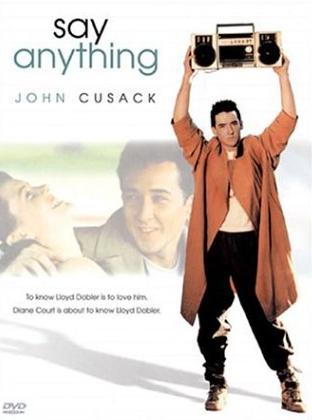

SAY ANYTHING . . .

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Cameron Crowe

With John Cusack, Ione Skye, John Mahoney, Lili Taylor, Amy Brooks, Pamela Segall, and Jason Gould.

Optimistic movies that are halfway believable — that base their hope on plausible characters and events rather than Hollywood magic — have become something of a rarity. These days the only optimism we seem able to abide comes from “inspirational” fantasies such as E.T. and (to cite a more current example) Field of Dreams, which offer little more than the satisfaction of infantile wish fulfillment. So the appearance of two better-than-average movies with optimistic attitudes, both of them personal romantic comedies credited to single writer-directors, is an encouraging sign at a time when the commercial American cinema seems to be teetering on the edge of a faceless, mechanical void.

There’s nothing really startling about either Say Anything. . . , Cameron Crowe’s first feature, or See You in the Morning, Alan J. Pakula’s 12th, except that neither one is a bore, an insult to the intelligence, or a remake of something else; and both have fairly large groups of well-defined characters and a central love story that is at once believable and positive.

Say Anything, which opened two weeks ago to favorable press and good word-of-mouth, in spite of its very unbeckoning title (which I’m not alone in not understanding), will probably be around for some time. See You in the Morning, which opened last week, is in some ways more ambitious; it seems to have less of a chance of acquiring an instant reputation and audience, so I’d recommend going to see it first — before it disappears to await resurrection in the video graveyard.

See You in the Morning deals with the diverse emotional adjustments and complications that ensue when a divorced psychiatrist and a widowed photographer, who each have two children, fall in love and get married. It has the unusual distinction of successfully delineating at least a dozen important characters in about two hours, not one of whom is a stock figure, but this pleasure is secondary to the revelation of seeing what Jeff Bridges, who plays the psychiatrist, Larry Livingston, can do when he is working full throttle and with the right kind of material.

While Bridges has always been reliable in intelligent, nice-guy performances, his range and density as an actor have been gradually diminishing into predictable typecasting. Last year’s Tucker represented the apogee of this tendency, flattening Bridges’s cheerful persona into a kind of one-dimensional icon (which served the movie’s preoccupation with promotional images) while freezing his shit-eating grin into what almost amounted to a death’s-head rictus. Perhaps attributable in part to executive producer George Lucas’s concern for image and design over substance, the characterization served fair warning that Bridges’s ability to represent something more complex than a magazine illustration — the kind of depth that he brought to his part in Cutter’s Way, for example — was in danger of evaporating.

Pakula’s part for him in See You in the Morning is clearly the kind of role he’s been needing, although interestingly enough it builds upon rather than departs from the frozen rictus image. Early on in the movie, his character is identified deceptively as a relatively flighty and nonserious sort of fellow. Eventually, though, when we see him working as a psychiatrist, we realize that his compulsive levity is a serious part of his professional equipment — his bedside manner, so to speak. And still later, when we come to understand better the insecurity and even despair that lurk behind this cheerfulness, his behavior comes across not simply as a false cover but as an active tool of negotiation between warring impulses.

The brilliance of Bridges’s performance here, which deserves the much-abused adjective “Brechtian,” is that as it illustrates Larry’s feelings and his diverse ploys for dealing with the world, it comments on them as well. Like André Dussollier’s performance as the lawyer in Eric Rohmer’s Le beau mariage, it allows us to see the wheels of calculation that turn behind every tactful gesture, as well as the wavering uncertainties, the barely perceptible cracks that are never quite papered over. The movie’s title refers to a popular ditty that Larry likes to sing to himself, and in a way this song functions for him just as his habitual smile does — it’s an expression that is sincere, yet also somehow willed rather than natural.

None of this would be very meaningful if it weren’t for the elasticity of Pakula’s script and direction and the caliber of the other performers that Bridges plays against — a wide-ranging group that includes the effective Alice Krige (a South African whose American accent is flawless) as Beth Goodwin, the photographer; Farrah Fawcett as Larry’s first wife; Lukas Haas and Drew Barrymore as his stepchildren; and even an emotional family dog. All of these actors (and several others) furnish Bridges with various behavorial tests, just as their characters present various challenges to Larry; much of what’s interesting about the movie is the degrees of ingenuity with which Bridges fields their different appeals.

The movie’s milieu is surprisingly close to that of certain Woody Allen films such as Hannah and Her Sisters and Another Woman — that is, the world of the educated upper crust of American society. Even the use of songs like “When I Fall in Love” (sung by Nat “King” Cole), “Embraceable You” (played by Clifford Brown), and “Our Love Is Here to Stay” (performed by jazz violinist Paul Peabody) conjures up a comparable ambience. But the difference between Pakula’s and Allen’s approaches to the same privileged world is telling.

While Allen’s movies are hyperbolically and self-consciously set in Manhattan, Pakula’s movie is incidentally and unobtrusively set in Manhattan. Where Allen’s characters are usually earmarked as either Jewish or WASP, Pakula’s could just as easily be one or the other. In contrast to Allen’s characters’ compulsion to analyze and discuss their psychic conditions at laborious length, Pakula’s characters simply act theirs out. Finally, and most important, while Allen is crippled by his slavish dependency on Bergman and Fellini as stylistic reference points — as a friend recently pointed out, even his delightful episode in New York Stories can be traced back to the Fellini episode in Boccaccio ’70 — Pakula seems here to rely more on personal experience to block out his story. The net result is that while Allen’s material remains semitheoretical — a sketch for a movie rather than the movie itself — Pakula manages to bring the same sort of material to life: life as it is lived, not as it is theorized about.

Part of the appeal of Say Anything is its refreshing freedom from most of the cliches and conventions found in so many other recent teen movies. Interestingly enough, the project grew out of conversations between Cameron Crowe and executive producer James L. Brooks about an intense father-daughter relationship, with the teen romance for the daughter only developing later. In the finished product, the father-daughter story is background and the romance comes to the fore.

Diane (Ione Skye) is a brilliant biochemistry student who wins a fellowship to study in England; her devoted, divorced, and well-to-do father (John Mahoney), with whom she has an intense and open rapport, manages a nursing home. Lloyd (John Cusack) — a year or two older than Diane but less ambitious and accomplished — is an Army brat; his parents live overseas and he lives modestly with his older sister (Joan Cusack, John’s sister in real life) and young nephew (Glenn Walker Harris Jr.). Lloyd’s only apparent interests are kickboxing — a form of boxing that incorporates kicking — and dating Diane. He and Diane are an unlikely match, and at first neither Diane’s father nor Lloyd’s friends Corey (Lili Taylor) and D.C. (Amy Brooks) think it has any chance of working.

Apart from some dubious information about the way Internal Revenue Service officials operate, and some overly neat and symmetrical business with a fountain pen, Crowe’s script is as fresh and insightful as his direction. Much of the credit for the film’s overall assurance is undoubtedly also due to the producer, Polly Platt (who collaborated on most of the best Peter Bogdanovich films, mainly as production designer, as well as on James L. Brooks’s Terms of Endearment and Broadcast News), and to the sensitivity of Cusack, Skye, and Mahoney.

If I’ve avoided saying anything much about the plots of either See You in the Morning or Say Anything, it’s because they’re relatively meaningless without the actors’ performances to tell us what they mean, emotionally and intellectually. In the case of Say Anything, which a friend has rightly compared to the early films of Truffaut, it’s the sheer delight in people that registers more than the specific events that occasion this delight — details like the irrepressible giggles of Diane (or the equally energetic and ecstatic cries of Lloyd’s nephew when he kickboxes with his uncle), or the wordless understandings that occasionally crop up between Lloyd and his friend Corey (as well as between Diane and her father). The love story is a central part of this delight, but far from the whole enchilada.

In See You in the Morning, on the other hand, the director’s emotional interest gravitates around Beth and Larry. It’s not that the others — their former spouses, Larry’s mother-in-law (Frances Sternhagen), Beth’s kids, Larry and Beth’s mutual friend Sidney (Linda Lavin), the dog, and even the houses that the families live in — aren’t accorded a lot of care and attention by Pakula. It’s that the film is a love story first and foremost, and it is basically the effect that these people and these houses and this dog have on Beth and Larry that determines the curve of the plot.

Whether a crowded love story of this kind is something of a contradiction in terms is an open question that the movie as a whole seems to be implicitly raising — how much, for instance, Larry’s success as a father and stepfather is or isn’t a part of his relationship with Beth. It’s a middle-aged issue in contrast to the more youthful perspective of Say Anything, and the emotional registers that are explored are every bit as nuanced.