From the Chicago Reader (September 19, 1997). — J.R.

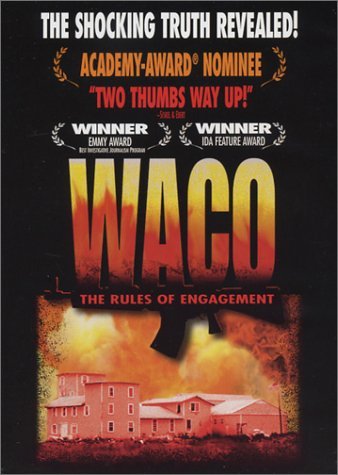

Waco: The Rules of Engagement

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by William Gazecki

Written by Gazecki and Dan Gifford

Narrated by Gifford.

At some point in the middle of Dog Day Afternoon (1975) Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino at his best) — a small-time operator and bisexual who’s taken over a bank to finance his male lover’s sex-change operation — has to step outside to bargain with the police. When it becomes clear that the crowd of bystanders and media that has gathered is more sympathetic to him than to the armed police, he calls out “Attica!” as a gesture of solidarity with the crowd and against the forces of law and order, which wins him more acclamation.

It’s a moment I recalled while thinking about the veiled allusion to the conflagration at Waco made by Timothy McVeigh on the day he was sentenced. This wasn’t because McVeigh, who has none of Wortzik’s charisma, qualifies as any sort of populist hero. It was because the fact that there can be no equivalence between the Waco disaster and the Oklahoma City bombing was apparently lost on McVeigh, just as the fact that there could be no equivalence between the slaughter of Attica prisoners in 1971 and robbing a bank was apparently lost on Wortzik — not to mention the crowd he was addressing.

Even so, it’s hard not to think of other grotesque pseudoparallels to Waco while watching the powerful and upsetting new documentary Waco: The Rules of Engagement, playing this week at Facets Multimedia Center. Stephen Holden wrote in the New York Times that it evoked “newsreels of war-torn Beirut.” I thought more than once of the gulf war, especially toward the end of the film, when one sees a good deal of the burning compound, tanks, and helicopters — and infrared videos shot from the air. I suppose one could go back further and find questionable parallels with all sorts of past incidents involving cultural, religious, political, and economic intolerance that led to the slaughter of innocents.

I think many of us feel compelled to come up with some kind of reference point for Waco because we lack information about the disaster; what we initially got from the media — a hasty and unsatisfying compost of government press releases — proved to consist largely of lies, so the gaps had to be filled with something. Whether this something was mythology about the Branch Davidians or mythology about the federal government, we wound up with a kind of demonology that seemed to make drawing historical parallels necessary to comprehend the horror of the event. The problem is, our knowledge of the historical parallels we choose usually turns out to be approximate at best, also fixed by a few mythological givens. For example, one doesn’t have to be a conspiracy theorist when it comes to the assassination of John F. Kennedy to conclude that cover-ups by city, state, and federal officials of their activities — including incompetence and covert actions — as well as those of organized crime, continue to make the full truth of what happened indecipherable.

Another reason we tend to mythologize is that the media, especially since the O.J. Simpson trials, have tended to do the same thing, concentrating most of their energy on a few subjects, regardless of whether the reporters are qualified to speak authoritatively on them. (The profound isolationism of this country in recent years was only intensified by the suspension of most world news to make room for the O.J. trials — putting us so far behind that the media seem to have given up on catching up.) This is why TV viewers over the Labor Day weekend were pretty much limited to hearing endless repetitions of the same facts about Princess Diana’s death or watching the Jerry Lewis telethon, with its evocations of an older, communal America that no longer exists. Apparently nothing else that was going on in the world had the same kind of mythological potential. (One brief alternative that I caught only proved my point: a CNN “report” about the Telluride film festival highlighting mainstream stars and directors, all of them hyping their work and parenthetically noting that what they liked about Telluride was its absence of hype and other mainstream rituals.)

An hour into Waco one hears a Branch Davidian woman say, “We the people don’t run this government anymore. They do, and they tell all the lies they want.” Given all that we’ve seen and heard up to this point, it’s hard not to agree with her — even if the task of figuring out who “they” are remains just as difficult as it was before the film began.

To its credit, this documentary begins by doing precisely what the media failed to do at the time of the Waco conflagration — explain who David Koresh was and what the Branch Davidians were, factually and not in terms of mythology or demonology. This doesn’t mean that we emerge with a comprehensive understanding, but at least we’re offered a plausible sketch — and one that contains a few surprises. (How many of us knew, for instance, that the Branch Davidians were multiracial and came from all over the world? Or that at least some of the people in Waco who knew Koresh seemed to like and respect him?)

When the film proceeds to the Senate hearings about Waco it’s initially just as lucid, particularly when it throws doubts on the claims of the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms about what happened; they insisted, among other things, that the ATF didn’t alert the press in advance about the attack on the compound, that the government forces didn’t fire first, and that they weren’t responsible for starting the fire that eventually killed at least 70 men, women, and children. But gradually Waco loses this lucidity. The scattershot sound-bite format interrupts some lines of questioning just as they start to become interesting, and the fragmented editing leads to certain confusions. The film only regains some lucidity when at the end it focuses on the confrontation between the government forces and the Branch Davidians. (Another problem is the often obtrusive music of David Hamilton; aren’t the doubts raised by this film about what happened in Waco disturbing enough to obviate any need for this kind of emotional goosing?)

The preview tape I watched increased some of the problems I had with the hearings footage; on the bottom of every frame was stamped PRESS VIEWING ONLY NOT FOR PERSONAL USE, which often covered up the printed identifications of the speakers, making it hard to be sure who was talking. This isn’t a problem that people who see the film at Facets will face, but I mention it because it’s a form of obfuscation that parallels the media obfuscation a film like Waco is designed to combat. And when a documentary about Waco becomes a marketplace object — thereby necessitating an ownership stamp — other forms of interference come into play.

Reviews of the film as it appeared at Sundance describe it as 165 minutes long — one in Variety mentions that this “running time likely will be a commercial handicap.” Sure enough, the version showing here is 30 minutes shorter, which may partially account for the frustrating sound-bite effect. Moreover, a story by Mick LaSalle in the San Francisco Chronicle alludes to director and cowriter William Gazecki’s dissatisfaction with the film’s middle section about the congressional hearings, which Gazecki says producer, cowriter, and narrator Dan Gifford forced him to put in. Does this suggest a conspiracy? No, simply a disagreement. But just as too many government and media agendas have made it difficult to find out what happened in Waco, too many filmmaking agendas — including simple differences of opinion about how to tell a story — can get in the way of the truth.

Gifford worked as a newsman for CNN and the MacNeil/Lehrer News-Hour, and Gazecki worked as a sound mixer on Hollywood features such as The Rose and Who Framed Roger Rabbit — so perhaps differences of perspective are to be expected. I’m sure comparable differences can be found among the employees of the FBI who speak at the hearings in the film — not only different perceptions of what happened, but of how (or whether) to express their positions and opinions. Yet it’s easier to speak — as I do here — about the claims of the FBI and the ATF about what happened, because it’s much easier to target institutions than specific individuals in power, particularly when those individuals prefer to stay hidden, or at least to keep their decision making out of public view. By the same token, I don’t know whether to credit Gifford or Gazecki for what I like and don’t like about Waco: The Rules of Engagement, so I talk about marketplace processes. Like it or not, we’re all stuck in the same mythological fix.