From Stop Smiling, issue 36, 2008. — J.R.

It’s easy to argue that most of the greatest filmmakers in the history of movies can’t be reduced to single nationalities, and that an uncommon number of them worked as expatriates. “I’m not at home anywhere,” declares Friedrich Munro (Patrick Bauchau), the expatriate director-hero in Wim Wenders’ underrated The State of Things (1982) — shooting an apocalyptic SF film in a remote corner of Portugal until money suddenly runs out and he has to chase down the producer (Allen Garfield) in Hollywood, who appears to be fleeing from the Mafia. This line is actually a quote from a real-life, very great German expatriate director with a similar name, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. And it might be argued that a condition of homelessness has helped more major filmmakers than it’s hurt, maybe because it’s forced them to reinvent themselves — a process that has also often entailed reinventing their cinema.

Some examples of this tendency may not be immediately obvious. Luis Buñuel is usually regarded as quintessentially Spanish, yet he only made three films that fully qualify as Spanish — a short documentary called Land without Bread (1932) and two features, Viridiana (1961) and Tristana (1970). Furthermore, Viridiana created such a scandal in Franco Spain that when it was rejected by the censors there, it was identified exclusively as a Mexican feature, simply because it had a Mexican coproducer and by then all its Spanish credentials on paper had been destroyed (a tale told by one of its two Spanish producers, Catalan filmmaker Pere Portabella). Tristana, on the other hand, stars Catherine Deneuve in the title role, a French actress whose Spanish lines had to be dubbed by someone else. And every other film by the “most Spanish of Spanish directors” is either French or Mexican. A line uttered by the title hero of Nicholas Ray’s western Johnny Guitar (1954), “I’m a stranger here myself,” eventually came to be adopted as a kind of motto by the wandering director himself, regardless of whether he happened to be filming in Hollywood, Canada, or the Sahara. This only helps to underline the fact that being an expatriate is not merely a possible life; it’s also a state of mind — and not just the mind of the expatriate. Charlie Chaplin was an Englishman who made almost all his films in the United States, returning to London to shoot only his last two features (A King in New York and A Countess from Hong Kong). Alfred Hitchcock directed 23 features when he was still in London, and 30 more after he emigrated to Hollywood — following the pattern of many German directors who started out successfully making films in Germany (Fritz Lang, Ernst Lubitsch, and Douglas Sirk– not to mention Murnau and Wenders) before shifting operations to the U.S. and elsewhere. Lang went first to France to make Liliom and much later made films in the Philippines, India, and back in Germany; Murnau, who’d already made excursions to European countries east of Germany for Nosferatu (1922) and The Grand Duke’s Finances (1924), made his last film, Tabu (1930), in the South Seas. Paul Verhoeven’s own career trajectory has led him from the Netherlands to Hollywood and back again.

One also has to consider Hollywood directors like Otto Preminger, Josef von Sternberg, Erich von Stroheim, and Billy Wilder whose artistic personalities were defined by their Viennese backgrounds. Sternberg and Wilder both made single features in Germany, and Sternberg, who made his last feature in Japan, also received part of his schooling in Queens, New York. But unlike Preminger, neither they nor Stroheim ever made a film in Austria, so it’s a matter of interpretation how much these four filmmakers were or remained expatriates as filmmakers.

***

Many important directors have spent portions of their careers globetrotting, including Michelangelo Antonioni (Blow Up, Zabriskie Point, his documentary about China, The Passenger), Bernardo Bertolucci (The Conformist, Last Tango in Paris, The Last Emperor, The Sheltering Sky, Little Buddha), Jean Renoir (films in Hollywood and Rome, The River in India), Roberto Rossellini (Germany Year Zero, Fear, India Matri Bhumi, The Rise of Louis XIV, Socrates), Jacques Tati (who had a multinational family background — Dutch, French, Italian, and Russian — and shot most of his last two features, Trafic and Parade, in Holland and Sweden), and Orson Welles (Othello, Mr. Arkadin, The Trial, The Immortal Story, Chimes at Midnight, and F For Fake). Some leading non-fiction filmmakers, like Joris Ivens and Chris Marker, have chronicled their globetrotting in their films.

A few independent spirits, both living and dead, ranging from Paul Fejos to Jon Jost to Dusan Makavejev to Max Ophüls to Jacques Tourneur, have been so footloose that, in spite of their pronounced national origins (Hungarian, American, Yugoslav, German, and French, respectively), they wind up making their films wherever as well as whenever and however they can. Fejos, an extreme example, went from making experimental films in Hungary to some memorable commercial films in Hollywood (such as Broadway and Lonesome) during the silent and early sound eras; then, walking out on his Hollywood contract, he made early talkies in France, Hungary, Austria, Denmark, and Sweden before switching his interest to ethnography and documentaries and making all his remaining films in Madagascar, Indonesia, Siam, and Peru. Jost, currently living in Seoul, has spent much of his career moving back and forth between the U.S. and Europe; Makavejev became a political exile from Yugoslavia after making his transcontinental masterpiece WR: Mysteries of the Organism, and Ophüls made films in Germany, Italy, France, Holland, and the U.S. (not always in that order), while Tourneur, like his father Maurice, directed films in both France and the U.S., with several excursions elsewhere in Europe and one to Argentina. Carl Dreyer, born illegitimately in rural Sweden, was adopted by a Danish couple in Copenhagen, where he was raised and continued to live for most of his life. Most people simply regarded him as Danish, but he also made features in France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden.

What about those blacklisted American filmmakers who wound up exiled in Europe from the 50s onward — John Berry, Jules Dassin, Cy Endfield, Joseph Losey — or other American leftist filmmakers such as William Klein and Robert Kramer who wound up as permanent Paris expatriates for what appear to be somewhat related reasons? Or Stanley Kubrick, who managed to continue his career as a Hollywood director by making eight of his 13 features in England?

***

I think all the filmmakers cited above have either benefited or at least haven’t been serious handicapped by working in other countries as expatriates. But there are others who haven’t fared so well, maybe because the meaning of their work is so firmly bound up with the cultures of their native countries. I’m thinking especially of Mohsen Makhmalbaf (Iran), Samuel Fuller (the U.S.), and Andrei Tarkovsky (Russia), and it’s possible that the same strictures might have applied to such Japanese directors as Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasuijro Ozu if they’d ever made any of their films abroad.

Makhmalbaf was raised in Tehran as a working-class fundamentalist. He was arrested at the age of 17 as a terrorist against the shah’s regime when he stabbed a policeman (an event re-enacted by some of the original participants in Makhmalbaf’s celebrated 1996 A Moment of Innocence), and he emerged from prison only five years later, during the 1979 revolution. He was still a fundamentalist when he started making films, but his steady evolution away from Islamic orthodoxy since the mid-1980s led to increasing problems with Iranian censors, some early work abroad (like his 1991 Time of Love, about adultery, shot in Turkey), and finally, after more censorship battles, exile, along with his filmmaking family. (In the mid-90s,he founded Makhmalbaf Film House — a radical film school whose main students were his own wife and children, and whose collective activities are charted in detail at www.makhmalbaf.com — and he has subsequently collaborated in diverse capacities on such major Iranian features as The Apple by his daughter Samira and The Day I Became a Woman by his wife Marziyeh Meshkini.) Initially he and his family concentrated on making films in Afghanistan (most notably, Kandahar in 2001); more recently, he’s made Sex & Philosophy (2005) in Tajikistan and Scream of the Ants (2006) in India, and it’s no pleasure to report that these and Kandahar are decidedly inferior to such Iranian features as The Peddler (1987), Marriage of the Blessed (1989), Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992), Salaam Cinema (1995), Gabbeh (1996), and The Silence (1998), all of which qualify in different ways as critical dialogues with Iranian society.

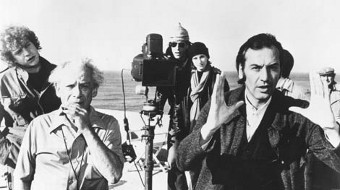

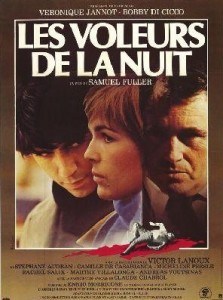

I think something comparable happened to Samuel Fuller when he moved to Paris from Los Angeles in the early 1980s, after the refusal of Paramount to release White Dog (another form of censorship) — which I consider his last great film — before he returned to Los Angeles in the mid-90s, shortly before his death. In his case there were also practical considerations, such as the fact that he was better known in Europe and thus could find more acting and directing jobs there. The inferiority of Fuller’s Thieves After Dark (1983), Street of No Return (1989), and The Madonna and the Dragon (1990) to his The Steel Helmet (1951), Pickup on South Street (1953), and White Dog (1984) stems from the unavoidable fact that America was his key subject, and its absence in his films left a gaping hole. This is most evident in Street of No Return — a David Goodis adaptation in which Lisbon has to double for a large American city where a race riot occurs. The issue isn’t whether or not a race riot can be imagined in Lisbon — it’s whether a Sam Fuller race riot can be imagined there. (White Dog, his clearest and strongest statement about and against racism, was later barred from prime-time TV because NBC deemed it “inappropriate”. “‘Inappropriate’?” Fuller once declared to me, indignantly recalling this judgment. “That’s turning up at a funeral in a jock strap.”)

I suppose stronger cases could be made for Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (shot in Italy, 1983) and The Sacrifice (shot in Sweden, 1986) than for either Scream of the Ants or Thieves After Dark — but not that these two features could be regarded as equal or superior in any way to Andrei Rublev (1966) or Stalker (1979). Indeed, it might even be said that Tarkovsky’s last two features are in many fundamental ways films about exile — which is a far cry from the existential alienation found in his Russian films.

***

Speaking as someone who lived for almost eight years as an American expatriate in Paris and London, I’d argue that my appreciation of American movies — and of America more generally — was broadened and deepened as much by what I saw and read in those two cities as what I encountered back home. This suggests that becoming an expatriate can sometimes be a single step in a much longer process of repatriation. Standing outside one’s own country makes a fresher perspective possible, and if I find Stroheim’s take on San Francisco in Greed (1924) a lot more stimulating than his take on Vienna in The Wedding March (1928), this isn’t necessarily or simply a matter of valuing his location shooting in the former over his studio recreations in the latter.

More generally, I find some of the freshest views of the U.S. to be found in movies coming from foreign visitors or expatriates — Jacques Demy’s in The Model Shop (1969), Emir Kusturica’s in Arizona Dream (1993) — even Paul Verhoeven’s in Showgirls (1995), especially if one reads Las Vegas as Hollywood. Or consider the view of San Francisco in Petulia (1968) that so enraged onetime Berkeley resident Pauline Kael — a movie directed by an American (Richard Lester) who’d become an English expatriate. What Kael found simply incorrect I found exhilarating as a fresh perspective. And if this perspective proves to be fantasy-driven, isn’t that what movies are sometimes supposed to be?