From the Chicago Reader (December 7, 1990). — J.R.

MISERY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Rob Reiner

Written by William Goldman

With James Caan, Kathy Bates, Richard Farnsworth, Frances Sternhagen, and Lauren Bacall.

Although it didn’t impress me too much when I first saw it, The King of Comedy has gradually come to seem the most important and resonant of Martin Scorsese’s features, largely because of all it has to say about the values we place on both stars and fans in contemporary society. Part of what makes it so pungent is the casting: by all rights, talk-show star Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) should be the “hero” and his crazed kidnapper-fans Rupert and Masha (Robert De Niro and Sandra Bernhard) the “villains”; but De Niro after all is a charismatic star in his own right, while Lewis has long been someone Americans love to hate. The same kind of twist on stereotypes occurs in the story: Rupert is an obnoxious loser and Masha a borderline psycho, but Langford’s offstage persona is so morose and unpleasant that next to him they seem like models of humanity. To make matters even more disturbing, Masha clearly regards Langford as a substitute for her own neglectful parents, and Rupert’s climactic stand-up comedy debut, won as a ransom for kidnapping Langford, largely consists of contemptuously trashing his own family and background. Implicit throughout Paul D. Zimmerman’s suggestive screenplay is the notion that our adoration of celebrities has a great deal to do with self-hatred, while the frequent aversion of stars toward their fans is similarly founded on self-hatred.

Misery, a psychological horror thriller adapted by William Goldman from a Stephen King novel and directed by Rob Reiner, lacks the scope, nuance, and self-awareness of The King of Comedy. But most of what makes it interesting, beyond its relative success as a pared-down genre exercise, is its exploitation of similar feelings about stars and fans. The fact that King’s own fiction often seems motored on self-hatred — particularly when his heroes are writers, as in The Shining and here — probably helps to seal this connection, and suggests as well that King’s self-hatred, like Woody Allen’s, has a lot to do with his popularity. King’s writers and Allen’s heroes are typically frustrated, twisted, and self-deprecating about their talents in spite of their self-absorption. (It was only when Allen owned up to his hatred for his own fans as well as himself, in Stardust Memories, that he risked losing his audience.)

While Misery’s plot, like that in The King of Comedy, centers on a crazed fan capturing a star, there are certain significant differences. The star in this case is a best-selling novelist named Paul Sheldon (James Caan), but the fan, Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates), a former nurse with a troubled, ambiguous background, has no desire to become a famous writer. Furthermore, Misery, unlike The King of Comedy, depends on a popular form of misogyny — that focuses on strong-willed, domineering, maternal, sexually unattractive women — for many of its effects. (Admittedly, The King of Comedy uses misogynist elements in a climactic candlelit scene between Masha and Langford — a scene that has a precise counterpart in Misery, even down to the male victim pretending to have some sexual and romantic interest in his female captor in order to gain an edge in the struggle. But it isn’t a consistent strategy in The King of Comedy, as it is here.)

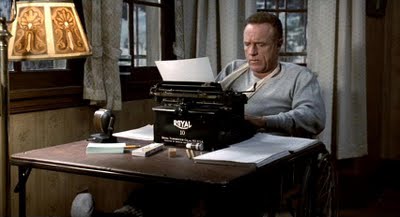

Sheldon’s fame rests on a series of period romance novels featuring a heroine named Misery — a series that he deeply despises and that the lowbrow Wilkes adores. He has just polished off his heroine for good — in a book that has not yet come out — in order to write a “serious,” quasi-autobiographical novel in his Colorado retreat. Triumphantly finishing his new work, he gets in the car with it to head for New York just as a blizzard is getting under way. Shortly into his trip he skids off the road and suffers a nearly fatal accident. Coming to the rescue, Wilkes carries his fractured, unconscious body off to her remote house and nurses him slowly back to health, keeping him locked in his room. Disgusted by the profanity in his new novel, she forces him to burn it; when the final Misery novel comes out, she is horrified to learn that Sheldon killed her off, and makes him promise to revive Misery in a new novel.

In counterpoint to this claustrophobic plot, we periodically cut away to the efforts of Sheldon’s New York agent (Lauren Bacall) to locate him, mainly through the services of a local sheriff and chief of police in Colorado (Richard Farnsworth). There’s a lot of pleasant homespun humor in the sarcastic, affectionate repartee between the sheriff and his wife (Frances Sternhagen) — a couple who don’t exist in King’s novel — and their function here appears to be to provide some relief from the main story and to present an upbeat model of male-female relations. (There may also be a certain carryover here from the footage of elderly married couples recalling their initial courtships in Rob Reiner’s previous directorial effort, When Harry Met Sally . . .)

Casting proves to be as crucial in Misery as it was in The King of Comedy, although the emotional overtones are quite different. James Caan — an interesting actor in the 60s (Red Line 7000, El Dorado, Countdown, The Rain People) whose talents started to dim as narcissism began to overtake his screen personality (The Godfather, The Gambler, Rollerball) — hasn’t been very visible in movies over the past decade, and seeing him here may produce a slight shock. Even before his character becomes an invalid, he comes across as a middle-aged jock, not as a writer at all. His features seethe with weary resentment, which may have led to his getting the part, but it remains pretty hard to believe in him as someone who’s physically incapacitated. While Sheldon is obviously the character we’re supposed to identify with — and for long stretches becomes the only one we can identify with — I mainly took him to be a rather supercilious creep, leaking hypocrisy from every pore, and found it difficult to determine how much of this was the filmmakers’ intention.

The much less well-known Kathy Bates, on the other hand — a stage actress who plays James Spader’s lesbian boss in White Palace and also had parts in Men Don’t Leave and Arthur 2 — gives a remarkably charismatic and kaleidoscopic performance; she has the uncanny knack of making the different characters she plays from one moment to the next plausibly add up to a single schizophrenic. While the script and story clearly make Annie Wilkes out to be a horrific monster (with occasional if trifling sympathetic shadings), Bates often makes her into a creature of touching humanity. Her acts may be monstrous, but thanks to Bates we feel an ongoing curiosity about her; Sheldon, by contrast, is interesting only insofar as we’re forced to identify with him.

Considering the dim-witted dialogue and horrific action Bates’s character has been saddled with, her success in giving this pasteboard construction some life and intelligence is little short of extraordinary. Her performance is basically what allows the movie to periodically veer in the direction of The King of Comedy, making the roles of celebrity and fan occasionally ambiguous. But in the final analysis she’s fighting a losing battle. Her efforts are at odds with the movie’s relentless misogyny, and the endless series of genre cliches the movie keeps tossing her way — everything from lightning illuminating her menacing features to her obligatory resurrection in the film’s climactic struggle — ultimately proves to be more than even she can transcend.

This is not to suggest that Sheldon’s character is any richer than hers. Indeed, he comes across so thinly that it’s hard to believe his “serious” novel could be any good, although this fact may be irrelevant; he represents stardom, not necessarily talent. “You may have just won next year’s American Book Award, my friend,” he muses to himself after completing this book in the King novel, shortly after we’re told that he greeted the death of Misery in his previous book with “hysterical laughter.” (Twenty pages later, we learn that he’s grown to hate his heroine so much that four years ago, for April Fools’ Day, he had written and printed for the benefit of a few friends a booklet in which she spends a “cheerful country weekend” screwing an Irish setter.) In the final scene of the movie, we learn that another “serious” novel of his has just been greeted with rave reviews in the New York Times, Newsweek, and Time, with literary prizes waiting in the wings. He tells his agent that he doesn’t care about that stuff because he wrote this book for himself, but he’s so shallow that it’s difficult to believe him. In the two-dimensional world this movie constructs, public validation is the only value and genre reflex the only reality.

Indeed, the major point of both novel and film seems to be that Sheldon is a “winner” and Wilkes is a “loser,” and that their status as winner or loser determines whether or not we like them. (This cynical worldview is surprisingly close to Woody Allen’s.) Therefore we’re expected to laugh at and feel superior to Wilkes’s treasured collection of Liberace records, her use of Spam in meat loaf, and her mispronunciation of “Dom Perignon,” while we’re supposed to be solemn and respectful about Sheldon’s cornball ritual of smoking one cigarette and drinking a glass of champagne after the completion of each book, which the movie presents as hip and suave, the way stars are supposed to behave. And presumably Wilkes’s crime in loving the Misery books can’t be equated with Sheldon’s crime in writing them, because at least he makes money for what he does. In short, the snobbish impulses that this movie repeatedly relies on are never allowed to apply to Sheldon, even though the novel — which I’ve only sampled — at least intermittently suggests that there may be more of Sheldon’s “true self” in the Misery books than he cares to admit.

Both the book and the movie are principally motored on the “Oh my God” style of writers like Richard Matheson in the 50s, a style that generates suspense through the unrelieved agony of the hero over endless stretches. (In the novel, Sheldon’s predicament is worsened by his addiction to the painkillers Wilkes gives him.) In prose, this kind of agony generally takes a stream-of-consciousness form, with many passages written in italics; in movies, this kind of excess usually gets stripped down into straight-ahead, subjectively shaped action, which tends to make it somewhat more palatable. But since “success” in a genre movie mainly boils down to successful counterfeiting — e.g., the periodic evocation of Bernard Herrmann’s music for Hitchcock in Marc Shaiman’s score — it’s something of a Pyrrhic victory at best.

Published in the Chicago Reader a week later:

To the editors:

May I correct a gaffe that crept into the last sentence of my review of Misery [December 7]? While I originally concluded that “‘success’ in a movie of this kind mainly boils down to successful counterfeiting,” the phrase now reads, “‘success’ in a genre movie mainly boils down to successful counterfeiting” — an inadvertent charge that takes in musicals, westerns, and anything else that might be considered a genre movie. Actually, I was only referring to movies like Misery — psychological horror movies derived from Psycho — not genre movies in general.

Jonathan Rosenbaum