The September 16, 2005 issue of the Chicago Reader ran a somewhat different edit of this piece. I’ve opted for restoring much of my original submitted draft in the first section, as well as my original title. –J.R.

Lord of War

*** (A must see)

Directed and written by Andrew Niccol

With Nicolas Cage, Ethan Hawke, Bridget Moynahan, Jared Leto, and Ian Holm

Winter Soldier

*** (A must see)

Directed by the Winter Film Collective

“Memory believes before knowing remembers,” begins the sixth chapter of my favorite novel, William Faulkner’s Light in August. This odd but accurate observation perfectly describes my misremembering of Winter Soldiers —- an account of the Winter Soldier investigation held by Vietnam Veterans Against the War in Detroit in 1971. I saw it in Cannes shortly after it was made, in 1972, and haven’t seen it since until recently.

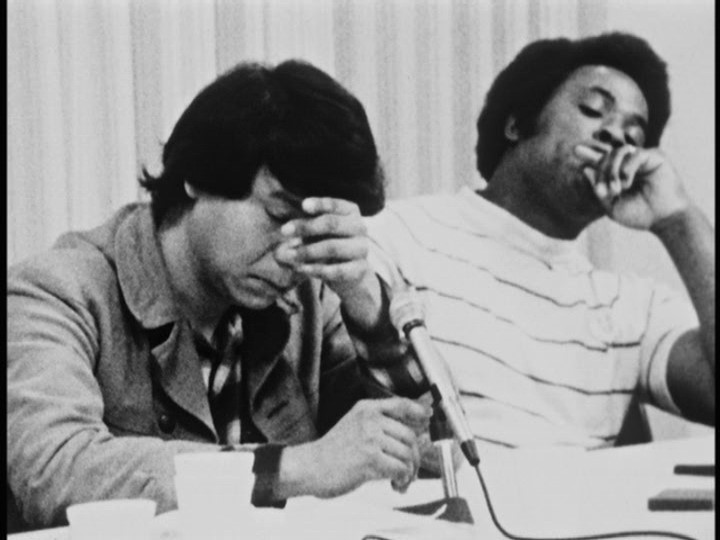

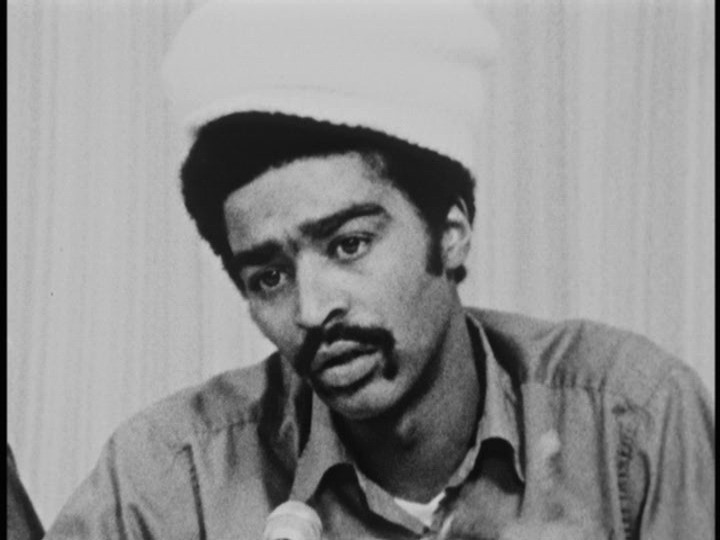

It’s almost as potent today as it was when I first saw it. But I recalled it being full of emotional breakdowns from the participants when in fact, apart from one Native American fighting back tears (who receives a standing ovation from many of the others), most of the soldiers’ testimonies are calm, thoughtful, and measured, in spite of the horrors they’re recounting. It was mainly my own silent tears, both real and imagined, that I was remembering.

For 33 years, I’ve persisted in thinking that this is the most important film document we have about this country’s tragic involvement in Vietnam. I still hold that opinion, adding that the scarcity of this film from public view can partly be explained by the fact that much of what it imparts about wartime atrocities and their sources in government policies is very hard to face and process. It’s even harder in some ways than photographs of tortures in the Abu Ghraib prison, because these are the subjective impressions and personal experiences of ordinary American soldiers and therefore easier to identify with. (At the time, the fact that many of them had let their hair grow long “disqualified” their statements for some reviewers —- an early example of what Times columnist Frank Rich has called “Swift Boating”.)

The soldiers also describe their fears, their grief at the loss of friends, their frustration at not having been able to understand the languages they heard or distinguish friend from foe. None of this justifies tossing prisoners out of planes, raping and murdering civilians, or randomly burning villages. But it does offer a context in which these and other criminal acts become comprehensible. It also had a clear therapeutic value for many of the speakers.

During the last presidential campaign, John Kerry’s supporters and opponents both alluded to the film and used clips from it, though not in a way that did any justice to the force and conviction of the testimony. As it happens, Kerry appears only briefly, asking a question near the beginning, and he’s only one of 30 vets seen over the course of the 95-minute film.

Winter Soldier isn’t the most informative American documentary about Vietnam from the viewpoint of the Vietnamese, a distinction that belongs to Emile de Antonio’s 1968 In the Year of the Pig. Instead it’s a kind of toxic potion made by and for Americans, its title derived from Thomas Paine’s 1776 statement “These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

I couldn’t call this film a masterpiece, only indispensable. It was directed by a collective of 19 people — some of whom, such as Barbara Kopple, have since become much better known and even celebrated — and the filmmaking is rather crude and perfunctory. But ultimately this is of little importance. What counts are the soldiers themselves and what they say. Their simple reality exposes the well-made, Oscar-winning, racist fantasies of The Deer Hunter as unconscionable acts of self-justification and self-deception.

Near the other end of the production-values spectrum is Andrew Niccol’s Lord of War, a caustic satire masquerading as an action adventure. Or maybe it’s Hollywood escapism masquerading as satire, but to the extent that it’s this it’s less satisfying. It stars Nicolas Cage — who coproduced and, according to Niccol, made the film possible — as Yuri, a Ukrainian arms dealer whose family fled to New York’s Little Odessa in 1980, pretending to be Jewish.

When the Soviet Union begins to fall apart in the 80s, Yuri takes advantage of the chaos to steal weapons and sell them to developing countries, especially in Africa — according to the press notes, between 1982 and ’92 over $32 billion in arms were stolen from Ukraine alone. Needing help, he hires his brother, Vitaly (Jared Leto), a coke addict who periodically has to be sent back to rehab, then starts doing business with dictators in places such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, insisting that he’s simply a middleman and has no moral responsibility for anything that happens.

Yuri tells the story in flashback — a wry, jocular, offscreen narration, well written by Niccol, that quickly becomes the heart of the film. Far from making him likable, it serves to demonstrate how adept he is at rationalizing his crimes. The film deals honestly with his denial and with his business, but everything else is generic Hollywood fantasy — entertaining lies. Smitten with a Miss World model (Bridget Moynahan), Yuri woos her by secretly renting an entire resort hotel, arranging to have the two of them be the only guests, and then meeting her “by accident” in the restaurant. Her discovery of what he does for a living after years of marriage has roughly the same degree of verisimilitude. His sexual trysts at weapons fairs and in the third world are no less fanciful soft-core fantasies, and the good-guy Interpol agent (Ethan Hawke) who relentlessly pursues him could have stepped out of a comic book version of Les miserables.

Some of this might be parody; when one African dictator asks to buy the gun used in Rambo, Yuri asks him which Rambo film. But basically Niccol is guilty of the same sort of contradictions he’s attacking: he recently told a Chicago audience that he bought 3,000 AK-47 rifles from a dealer to use as props and later had to sell them back to the same dealer at a loss.

On the other hand, in Yuri’s climactic speech he declares that the biggest arms dealer in the world is the president of the United States, rivaled only by the heads of the other permanent members of the UN Security Council. This thought isn’t new, but one doesn’t expect to hear it in a commercial action picture.