This essay was proposed to Another Gaze, an excellent feminist journal based in the U.K., in June 2020, lightly revised with their helpful suggestions over the next several months after I received a go-ahead from them, and still hadn’t appeared by October 8, 2021. I wished them well, but the editor was no longer responding to my emails, which is why I posted this essay here. P.S. My thanks to Scott Moore for pointing out several typos in the original posting of this piece, now corrected.

P.P.S. (12/16/21): I’m reposting this to celebrate the arrival in my mailbox of the hefty new issue of Another Gaze, including my essay, where I find myself among such fellow contributors as my old pal Lizzie Borden and A.S. Hamrah. My apologies to the editors for my journalistic impatience; it was well worth the wait. — J.R.

,

Long before the Coronavirus pandemic set in and many of us suddenly had more time to explore new modes of online viewing and even canon-building, I had been trying to develop and expand my limited acquaintance with the films of Kira Muratova (1934-2018), initially sparked by my 1989 encounter with her masterpiece The Asthenic Syndrome (1989) at the Toronto film festival, two years after I began my twenty-year stint as the principal film reviewer for the Chicago Reader.

As a subsequent member of the New York Film Festival’s selection committee in 1994-1997 (a committee which had previously rejected The Asthenic Syndrome), I tried and failed to get any of her other films accepted. And ever since I retired from the Reader in 2008, I’ve been trying to see more of Muratova’s work whenever and however I can.

It’s worth considering why Muratova’s cinema is apparently considered beyond the pale by mainstream American arthouse taste. Part of the Western resistance to her films can undoubtedly be traced back to a Cold War ideology that also helped to block appreciation and understanding of radical Soviet-bloc filmmakers such as Věra Chytilová, Miklós Jancsó, and Dušan Makavejev. As I’ve argued elsewhere, films like Chytilová’s Something Different (1963) and Daisies (1966), Jancsó’s Red Psalm (1971), and Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) are far more radical politically as well as formally than, say, Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968), Bernardo Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution (1964), and Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), and yet it was mainly the latter Western European arthouse films that captured the imaginations and interest of Western progressives during the 1960s and 1970s. Apart from the linguistic barriers pertaining to Czech, Hungarian, and Serbo-Croat, a relative lack of familiarity with those societies and cultures perhaps led to the reduced legibility of their films to Western viewers. It seems to me that this was, and still is, a situation shared by Muratova’s films.

An important part of what makes them ‘difficult’ is the unusually aggressive kind of dialogue delivery that Muratova favours, which her English language biographer Nancy Condee traces back to her most influential teacher in film school, Sergei Gerasimov, a former actor with the radically ‘neoexpressionist’ F.E.K.S. (Factory of the Eccentric Actors) in 1920s Leningrad. Yet it’s clear from Vladimir Nepevny’s excellent 48-minute documentary Kira (2003) — available on the same Russian Cinema Council (Ruscico) DVD as Chekhovian Motifs — that many Russians not only tolerate Muratova but adore her. The fact that she habitually works with a team of favourite actors and crew members, just like Ingmar Bergman or John Ford, only adds to her appeal and her legendary status, although, as suggested above, Western audiences have very little sense of this.

Since that first encounter, and writing now as a freelancer, I’ve gradually arrived at the conclusion that any public engagement with Muratova in the West is likelier to come via personal initiatives with the assistance of YouTube and various pirate sites than through capitalist distribution and exhibition or such institutional gatekeepers as the New York Film Festival (or even the Chicago Reader, for that matter). Speaking broadly, the cornucopia of filmic choices now offered on (and by) the Internet has had wildly different effects on individual viewers. Some are frightened (or at least intimidated) by the challenge and retreat conservatively into ever-narrower selections of box office champs and Oscar winners; others are thrilled by the prospect of discovery and adventurous exploration. Given the profusion of available titles, both polarities tend to be increasingly directed by lists, which, of course, have a very long history. (Andrew Sarris’ highly influential volume The American Cinema, essentially a book of ordered lists, already nurtured this tendency in the 1960s and 1970s, as did the preceding French criticism of the 1950s.)

Yet one should also consider the alternative paths chosen in composing canonical lists. When Penelope Houston and Peter Wollen jointly launched the Cinema One book series at the British Film Institute in the 1960s — an influential line of volumes that would include Richard Roud’s early monographs on Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Marie Straub (the latter then defined as a solo artist, before his partner Danièle Huillet was credited as an equally important participant in the filmmaking), Wollen’s own Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, and separate studies of, among others, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Rouben Mamoulian, Luchino Visconti, and Orson Welles — one striking difference between the books commissioned and edited by Houston and those overseen by Wollen was that the former routinely and conventionally dealt with films in chronological order whereas the latter expressly forbade this method of organization, requiring the author to come up with a different structure and different rationale for that configuration. An obvious advantage to following one’s own desires and predilections rather than a conventional academic syllabus, whether the focus is on Muratova or any other film-related interest, is that in the course of ferreting out and defining one’s chosen subject and predilections one is obliged to become an active (and not merely reactive) critic and canon-builder.

Bearing this difference in mind, one distinct disadvantage for me in attempting to tackle Muratova’s films chronologically is the fact that her first films are either unavailable to me (her codirected features with her first husband, Aleksandr Muratov, By the Steep Ravine [1961] and Our Honest Bread [1964], and her codocumentary with Theodore Holcomb, Russia[1972]) or of lesser interest to me. Her first two solo features, Brief Encounters (1967) and The Long Farewell (1971), both in black and white, which she has ironically labeled ‘provincial melodramas,’ seemingly have few of the transgressive qualities that have attracted me to her other films, even though the first of these had only marginal exposure prior to glasnost and the latter, for reasons that are far from immediately apparent, was originally banned altogether. Consequently, the main source of interest for me about these films is my curiosity about what was once perceived to be transgressive about them, and this curiosity may be better satisfied by Nancy Condee’s chapter on Muratova in her The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) —specifically, by what Condee calls the ‘fragmented characters’ in Muratova’s work, which for me reflects her separate Romanian, Jewish, Russian, and Ukrainian identities — than by wrestling with the films themselves. And I would defend this attitude on a practical rather than an intellectual basis, readily admitting that the shortcuts and potential misunderstandings that it entails are the inevitable side-product of the exploratory bricolage that I’m employing and espousing here.

Rather than adopt either Houston’s chronologies or Wollen’s structural principal of organization exclusively, I propose to combine portions of both approaches by tracing the use of repetition through a few of Muratova’s features, some (but not all) of which are considered in chronological order. This is only one way of illustrating the disarming lesson that what is most provocative and sometimes pleasurable in both art and life can also sometimes be most maddening and sometimes aggravating. Her films, in short, have a disconcerting way of flirting with us and slamming various doors in our faces, sometimes doing so simultaneously, and I’ve tried here to come to terms with that duality by emulating and reproducing it in a mimetic fashion. I’d like to suggest that a double-edged attitude of love/hatred towards both repetition and various institutions promoting an overall sense of continuity and coherence, including family and the state, lies at the heart of Muratova’s cinema, and may even help to account for much of its bipolar energy.

While the ultimate effects of the Covid-19 crisis on both viewing habits and the construction and maintenace of various film canons is still unclear, I would like this essay to serve as an exploration of some of the possibilities arising from this set of conditions., which have only intensified certain tendencies already provoked by digital viewing and access to the Inteenet. More generally, I will offer these samplings of my own haphazard discoveries and notations not as models for others to follow but as examples of the sort of viewing and analysis available to individuals using the resources of the Internet (as well as other materials) to match their own inclinations. And for those who object to online viewing as an asocial activity that undermines the communal aspect of filmgoing, I would counter that (1) online viewing reconfigures the social aspects of cinema without necessarily eliminating them (so that blogging and articles such as this one become part of the reconfiguration) and (2) the social and communal aspects of public filmgoing have already been thoroughly undermined by the film industry itself via targeting and other ways of subdividing audiences, as well as by the asocial aspects of mobile phones and the oxymoronic characteristics of ‘social media’ when they overtake public spaces.

Starting my discussion with Muratova’s third solo feature, Getting to Know the Big Wide World (1978), her first in colour, my main textual reference points are Jane Taubman’s six pages in her 2005 monograph on Muratova (London/New York: I.B. Taurus, 2005), Veronika Ferdman’s 2013 essay (http://www.lolajournal.com/4/world.html), and my 2005 capsule review for the Chicago Reader, written when I initially saw the film at a Muratova retrospective:

“Kira Muratova’s flaky 1978 feature, said to be her favorite, also goes by the title Understanding Life, but as often happens with her movies, appreciation ultimately triumphs over understanding. A loosely plotted comedy about a romantic triangle, set in and around a rural wasteland, it alternates between silence and sound, stopping and starting, with the cheekiness of 60s Godard. The relative chaos of the construction-site location, like the ones in Alexander Dovzhenko’s Ivan and Aerograd, is what Muratova seems to like most about this. As usual with her movies, the actors—including regulars Nina Ruslanova and Sergei Popov—are wonderful.”

The multiple pleasures — indeed, the joys — of Getting to Know the Big Wide World are largely a matter of sensual repetitions and echoes involving noise and quiet (intervals of silence on the soundtrack become as visceral as abrasive mechanical sounds or patches of solo piano), motion and stasis, melody and speech, rhymes of colour and visual patterning, interplays of sight and sound, action and reaction, montage and performance art in which a splash becomes a giggle, a screaming argument morphs into an automotive rumble or a song. As in Boris Barnet’s By the Bluest of Seas, one feels at times that the erotic-romantic triangle becomes musical, the diverse voicings and blendings of three human instruments.

Appreciation becomes a mode of understanding — appreciating life — as one poetic speech about the value of love is given twice: first heard as a disembodied, anonymous woman’s voice against a backdrop of silence, it is repeated as an amplified, celebratory announcement by Lyuba at a wedding, and finally recalled in a conversation she has with Misha. Elsewhere, a shot that traces the movement of someone walking is reprised and continued by the forward drive of a truck. Even the liquid names of the three leads—Lyuba, Misha, Kolya—become parts of the film’s musical refrains, along with their separate emotional timbres (yearning, gentle, macho-aggressive), while the twin girls of the building crew and the strategic employments of mirrors in the mise en scène suggest other forms of repetition.But If all this adds up to the standard Soviet socialist realist charge of formalism, it’s arguably formalism with socialist-realist as well as hedonistic aims and consequences — and why do these separate values habitually have to be seen, at least in the West, as being in conflict? (Muratova’s parents, one should note in passing, were both highly ranked Communist Party members.) Sometimes the sound carries the image and sometimes these priorities are reversed. Either way, the exuberance becomes shared, collectivized. And almost all of it takes place in a muddy field.

It’s impossible for me to be a completist about Muratova’s filmography when some titles (e.g., Sentimental Policeman [1992]) haven’t yet been subtitled in English, but it appears that her ‘discovery’ of verbal repetition in Getting To Know the Big Wide World had major repercussions on the remainder of her career and perhaps most consequentially on her final feature, Eternal Redemption: The Casting (2012). Much as Elaine May chose in her mid-80s to play an elderly woman losing her memory in her 2018 Broadway stage performance in Kenneth Lonergen’s The Waverly Gallery, presumably in order to stare down her own personal fears about senility by illustrating and embodying them in a black comedy, Muratova’s last film mostly consists of the same scene endlessly repeated with different actors, settings, and mises en scène before we belatedly discover that the film’s (fictional) director died in the midst of shooting and that its producers and editors are still trying to decide what to do with this intractable footage. It seems logical that Muratova’s final work would concern the difficulties the ‘normal’ world might continue to have with her transgressive cinema, this film included.

***

I’ve decided to skip over Muratova’s next feature, Among the Gray Stones (1983)—even though I enjoyed most of it after downloading it without subtitles from YouTube and finding English subtitles for it elsewhere—because she disowned it and even took her name off it after she lost control over its editing, crediting the film pseudonymously to ‘Ivan Sidorov’. Her following feature, Change of Fortune (1987), also sometimes known as Change of Fate or Change of Destiny—Muratova’s idiosyncratic adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s story ‘The Letter,’ about a British wife in Singapore who shoots her lover (which served as the basis for Maugham’s 1927 play and William Wyler’s 1940 film, neither of which Muratova was familiar with)—begins with a scene and dialogue between the adulterous couple inside a huge greenhouse full of trees and other vegetation, a scene that is immediately repeated aurally and with the same actors, but not cinematographically. We eventually learn that this repetition corresponds on some level to the woman revising and rehearsing her prepared testimony at her murder trial. Her original claim that the murder was in self-defense after an attempted rape (seen in the first version) has to be altered after a passionate letter she sent to her lover emerges as part of the trial evidence.

Then a third, partially whispered version of this dialogue is heard over another set of images moving into a cavelike setting, followed by a scene with the woman washing herself with the help of a male servant inside her prison cell before we return to the adulterous couple repeating portions of their dialogue yet again, apparently inside the same greenhouse, but this time in amorous close-up. Finally, a warden enters the heroine’s cell and delivers a racist monologue about the superiority of ‘white’ people, who need to ‘stick together’. Next, he introduces her to three people who will provide her with some ‘light entertainment’. `

Without harping too much on the naturalistic pretexts for repeating the opening dialogue several times, I suspect Muratova’s taste for repetition has more to do with her own activity as a filmmaker than it does with her heroine’s deliberations. From Taubman’s account of this film, we learn that the trio providing ‘light entertainment’ (one makes faces, a second performs sleight-of-hand magic, a third chews glass) are introduced simply because Muratova liked them and because they had previously been cut out of Among the Gray Stones—a capricious form of impulsiveness, seemingly like the racist speech, that suggests another parallel with 1960s Godard, the determination that one can insert anything and everything into a film. Condee notes that Muratova’s ‘most beloved eccentrics are those who, as she does, produce their own private art –most characteristically, bad art with no value other than its psychotropic effect’, which gives her work a certain kinship with early John Waters as well.

At this point, I’ve described — and in fact seen — only the first seventeen minutes of Change of Fortune, omitting from my account the heroine’s periodic crocheting because I couldn’t find a way of incorporating it. Rather than watch or attempt to synopsize any more of the film now, I’d rather save the eighty-odd remaining minutes for some rainy day when I could use some ‘light entertainment’ and good/bad/psychotropic art of my own, rather than when I need to think about finishing this article. And inspired by Muratova’s transgressive example in shirking my ‘commercial’ duties (and exercising an irresponsible and perhaps irritating option that would be unthinkable if I were attending a theatrical Muratova retrospective), I’d like to leapfrog over her 1989 masterpiece The Asthenic Syndrome (which I’ve written about elsewhere), the aforementioned Sentimental Policeman, her relatively popular 1994 Passions (apparently her only film that’s currently available on an American DVD), her Three Stories (the feature of hers that I tried and failed to get into the New York Film Festival in 1997), and her Second Class Citizens (2001), which I recently had the pleasure of discovering on YouTube, to conclude my abbreviated survey with what must be the craziest of all her black-and-white features, Chekhov’s Motives (2002, also known as Chekhovian Motifs), where her incantatory uses of repetition are especially evident. It’s also something that fascinated me at the time, and as I’m not afraid of repeating myself either, here is my Chicago Reader capsule review:

“Members of a farming family incessantly repeat the same lines of dialogue while a student prepares to leave home for school; guests at an interminable wedding cackle maniacally while the ghost of the groom’s lover interferes with the ceremony. Born in 1934, the great Russian filmmaker Kira Muratova (The Asthenic Syndrome) seems to get wilder and more transgressive with every passing year. This updated merging of two early Anton Chekhov texts (the short play Tatiana Repina and the story ‘Difficult People’) veers closer to the mad lucidity of Gogol than to the wry realism of The Cherry Orchard. I found the extreme stylization mesmerizing, hilarious, and ultimately closer to hyperrealism than to absurdism, though if you enter this without any warning you might wind up fleeing in terror.”

The aforementioned ‘merging’ has the student eventually hitching a ride with someone driving to a rural wedding rather than to his school in Moscow. Shorn of its repetitions, ‘Difficult People’ (1886), readily available in a Constance Garnett translation (www.online-literature.com/anton_chekhov/1185/), has basically the same settings, plot, and characters as Muratova’s adaptation, at least until the son leaves home, but its mood and style are drastically different. (In Chekhov’s story, the son returns home to berate his father for his selfishness before leaving again — something he does in this film as well, but only after he attends the wedding.)

At the protracted family meal that dominates the first sequence, multiple repeated phrases seem to function as weapons, as assertions of identity, as tantrums and other forms of delirium, whether these are the student’s requests for money from his father, the father’s lists of his expenses, the mother’s requests to the father to buy the student a sweater (or her affectionate addresses to a kitten), or two of the youngest boys’ assertions, begun in an earlier sequence, that a barn and not a pet food shop — or a pet food shop and not a barn — is being built in the muddy farmyard (to cite only five examples of repeated phrases). And because the fictional worlds of Chekhov are full of commonplace statements, Muratova’s insistence on turning them into manic mantras (that is, mantras that are anything but meditative, and delivered passionately rather than mechanically) seems at least partially a function of considering how strange they might sound or become — and how they might reduce, elevate, or at least level out a family meal by being treated as a strident form of music, a roundelay of refrains — a relation that is even acknowledged in this film’s title. (We even see an infant nodding rhythmically and sleepily to one of the father’s tirades, as if being ‘conducted’ by it.) This description hardly does justice to the complex construction of this sequence — including the calming effect that a film of a ballerina, seen on television when a teenage daughter turns it on and composed of lap dissolves, has on the mother, which literalizes the musical aspects of the preceding quarrels by substituting another kind of music and motion. Needless to say, this segment is entirely Muratova’s invention and has no counterpart in Chekhov. But the following shots of carpentry, pigs, geese, and chickens accompanied by an offscreen lieder sung by a male voice (in fact, a song previously composed for and heard in Getting to Know the Big Wide World), then shots of a turkey rooster and horses accompanied by the sound of sawing, differs from the Chekhov story only in the addition of the lieder, which carries over some of the lyrical and meditative feeling of the ballet.

I haven’t been able to read Tatiana Repina (1889) — a one-act play written by Chekhov in one sitting as a private joke for his friend Alexy Suvorin, conceived as a sequel to Suvorin’s four-act comedy of the same title, and intended neither for publication nor for performance. Yet Muratova’s version of it, running for 70-odd minutes, seems to be every bit as faithful or as unfaithful as her 40-odd-minute rendition of ‘Difficult People’, at least in terms of its more obvious details of character, action, and setting rather than its language, which I can’t comment on directly. (I can, however, note with amusement that Taubman reports that Muratova retained most of Chekhov’s dialogue ‘word for word’ while Condee insists that ‘the original texts are barely discernible in Muratova’s renditions’—a perfect illustration of how much subjectivity Muratova can provoke in her commentators, myself included.)

As indicated in my capsule, most of the film’s second section consists of a complete and interminable church wedding, and the maniacal cackling or giggling of various attending guests periodically calls to mind Eugene O’Neill’s virtually unproduced and unproducible 1925 Lazarus Laughed: A Play for Imaginative Theatre, which requires over a hundred masked actors and the almost continuous laughter of its title character. Otherwise, the degree to which repetitions are already an integral part of Russian Orthodox wedding services means that Muratova doesn’t need to add any, as she does to speeches in ‘Difficult People’; as in certain films of Luis Buñuel, one is made to feel at times that Christianity might be regarded as the ultimate surrealism. Once the ceremony is over, the groom tells a friend three times in a row that now is the time for them to go to the cemetery, presumably in order to make sure that his suicided mistress, whose ghost he saw at the wedding, is dead and buried there. While striding out with his friend and bride into the sunlight, he bellows out the same lieder that we heard in the farmyard to the strains of an offscreen piano. Then we and the farmer’s son listen to idle chitchat from the priests, and the hooded ghost reappears, only she proves to be not a ghost at all but the daughter of one of the priests who wanted to disrupt his wedding service. (In Chekhov’s play, Taubman informs us, she was a friend of the dead mistress.)

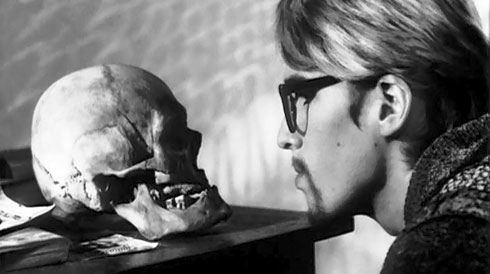

Back at the farm, after the son’s berating of his father devolves into a screaming match in front of his mother, we see him contemplating a human skull in his bedroom like Hamlet, collapsing on his bed, and cradling the family’s kitten. After the clock strikes five, he saddles a horse and says goodbye to his family, including his father. In interviews, Muratova maintained that the reason why she made Chekhov’s Motives was to support love and family values—and, unlikely as it sounds, there is reason to believe she was being sincere about this. The film ends conventionally, in spite of all its preceding violations of conventions, and bearing in mind that The Asthenic Syndrome begins at least allegorically with the grief, rage, and despair (rather than any sense of liberation) aroused by the death of Stalin, one could indeed argue that conservative and reactionary sentiments are every bit as operative and as relevant in Muratova’s oeuvre as radical and rebellious impulses. One might even conclude that the conflicts between these feelings and reflexes are what keep her works alive and challenging, so that reaching back towards the Communist dreams of building a future in Getting to Know the Big Wide World or towards the humanist values of Chekhov in Chekhov’s Motives ultimately means testing them against the horrible uncertainties of the present, and letting the chips fall and scatter where they may. Within this framework, rejecting or embracing one’s family or one’s state may ultimately and tragicomically prove to be two alternate versions of the same maniacal process. Such, in any case, is my current presumption in an investigation that is still fully in progress.