This was written in December 2008, after Dana Linssen, the editor-in-chief of the independent Dutch film monthly de Filmkrant, sent out a request early that month for contributions to what she called a “Slow Criticism” dossier, to appear in their special English-language newspaper at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in late January. I revived it in 2011 as my own contribution to the avalanche of journalism that had been appearing about Pauline Kael, capped by Frank Rich’s lengthy piece in the New York Times; it’s also included in my most recent collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, where it concludes the book’s penultimate section, “Films,” just before its final section, “Criticism”. There isn’t a piece about Kael in the final section, but this broadside helps to explain why.

One aspect of recent journalism about Kael that seems to confirm the provinciality of American film criticism in general is the tacit assumption that “the world of film” in the U.S. is somehow (and automatically) coterminous and equivalent to global film culture — unless the assumption is simply that global film culture is too esoteric and inconsequential a subject to be worthy of discussion in the U.S. But it’s worth stressing that outside the English-speaking world, Kael’s critical status was and is pretty limited. And it’s also worth arguing that de Filmkrant‘s “Slow Criticism” is a good indication of the vanguard of a more international form of film criticism in the English language, conceivably more pertinent to that discourse than Kael’s writing has ever been.

Dana described what she wanted as follows: “The SLOW CRITICISM dossier is meant to be an explicit refuge for wayward articles that too seldom find their way to print, because they are too philosophical, personal, political, or poetic. Their focus can be diverse, from neglected directors to ponderings on the metaphysics of cinema. At this point we want to be as open as possible for any brain-wave you might have.

“We reckon most of you must have a cri de coeur like that lingering in the back of your heads (and hearts).

“But we are demanding! We are aiming for texts that are urgent and burning. The world will have to stop turning if they’re not published right now. They have to be dragged from the gates of hell (and heaven alike). They should alter our filmic eyes all over again.”

This was a tall order, and I don’t know at all if the following meets it. But I had just reseen the first two parts of The Godfather after having recently purchased the new DVD box set, which is what led me to propose the following. (I had previously written on Part III for the Chicago Reader, and had originally reviewed Part II a mite skeptically for the Summer 1975 issue of Sight and Sound.) My thanks to Dana for generously allowing me in 2009 to run the piece here a little in advance of its publication in the Slow Criticism dossier. — J.R.

Revisiting The Godfather

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Although I vastly prefer Citizen Kane (1941) to The Godfather (1972), one facet of both films that gives me some pause — especially because I believe this facet has something to do with the current and unquestioned status of both movies as towering masterworks, not simply superb entertainments — is their worship of power, including their capacity to view corruption from a corrupt vantage point. Both movies are melancholy and wistful about their conviction that corruption is an inescapable part of American life in general and The American Dream in particular, and maybe I wouldn’t mind this attitude quite so much if its metaphysics weren’t so glib and absolute in its defeatism.

After all, accepting gangsterism along with its built-in denial as essential and inescapable parts of our condition has a lot to do what made the gangsterism/denial of the Bush era so rampant, everyday, and taken for granted, at least until the possibility of overcoming it was implicitly posed by the Obama campaign. In his book GWTW: The Making of Gone With the Wind — published the year after The Godather’s release, when some commentators were already touting it as that late 30s blockbuster’s natural successor — Gavin Lambert perhaps said it best: “When the most ruthless level of private enterprise becomes widely taken for granted, a film like The Godfather finds there are no questions left to be asked. Its characters exist in a nightmare which they (and the audience) accept as everyday reality.”

What Citizen Kane has that Orson Welles’ other films lack is the contribution of Herman G. Mankiewicz , whose caustic wit is valued by some for its comforting assurances about the inevitability of corruption. The more innocent and ultimately destabilizing view of corruption shared by Welles’ other films — that is to say, their lack of cynicism — surely has something to do with their failure to be fully assimilated into the American mainstream. For the Pauline Kael who viewed Kane as “kitsch redeemed”, the notion that The Godfather could be viewed as a different kind of kitsch rather than as a noble Shakespearean tragedy is never considered, because there are certain ideological givens about American violence and power, even at their most infantile and unreasoning, that are too serious to be scoffed at, especially when they’re bathed in “Rembrandt” lighting. By contrast, consider all the depictions of violence in such otherwise very different films as Renoir’s The Rules of the Game and Jarmusch’s Dead Man, which refuse the very possibility of violence having any kind of dignity whenever or however it occurs. Mythologies about macho power and the pride of wanton blood-spilling are arguably at the roots of what put George W. Bush twice into office, but this is something we’ve generally allowed ourselves to laugh at only after it’s too late to undo most of the damage. This also helps to explain why American reviewers generally showed themselves to be incapable of stepping beyond the critical framework dictated by the pressbook of Oliver Stone’s Nixon and insisted on employing the word “Shakespearean” in their reviews — thereby glamorizing the film and, more implicitly, Nixon’s own skuzzy exploits. (At least Herman Mankiewicz never tried to position himself as a Shakespeare — apparently being content to accept the more modest mantle of, say, a bush-league Thackeray.)

This development can perhaps be traced in part back to Pauline Kael’s use of the adjective “Shakespearean” near the end of the first paragraph of her review of The Godfather, Part II. Her second paragraph — which casually identified its predecessor as “the greatest gangster picture ever made,” immediately after announcing that Part II “enlarges the scope and deepens the meaning” of its predecessor — marked the lamentable suspension of her Orwellian scoffing at pretension that was perhaps the strongest virtue of her early criticism. In terms of her own unapologetic trash aesthetic, a far better candidate for “greatest gangster picture” would surely be the Hawks-Hecht-Hughes Scarface, no less arty than Coppola’s blockbuster but far more exuberant and irresponsible (and far more honest about its own amorality), and in most respects closer to the starkness of Greek tragedy, incest and all, than to any Shakespearean tragedy or historical melodrama.

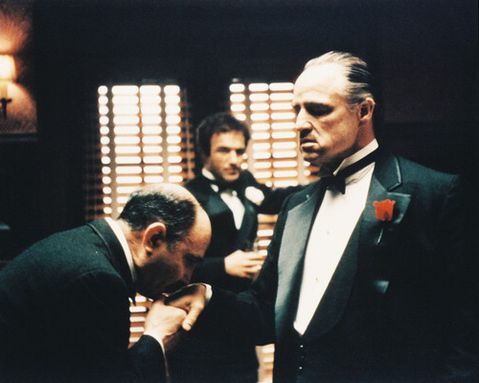

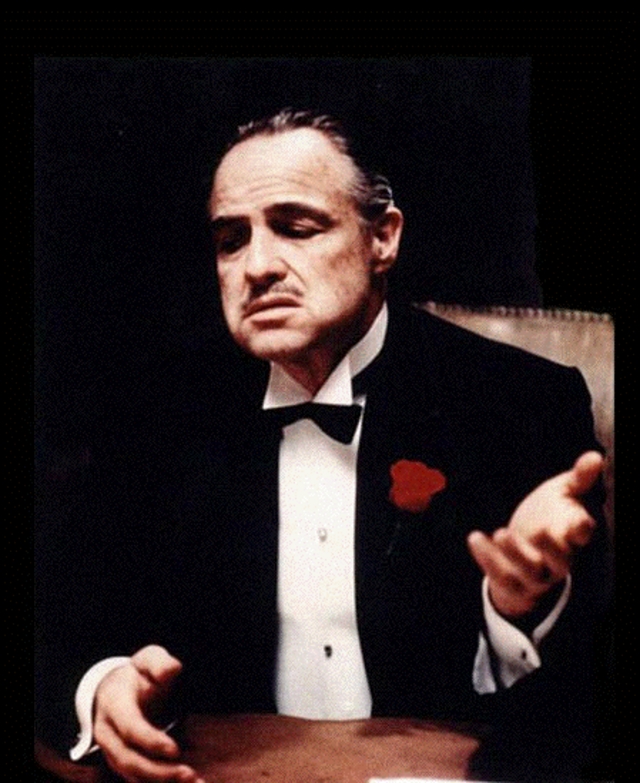

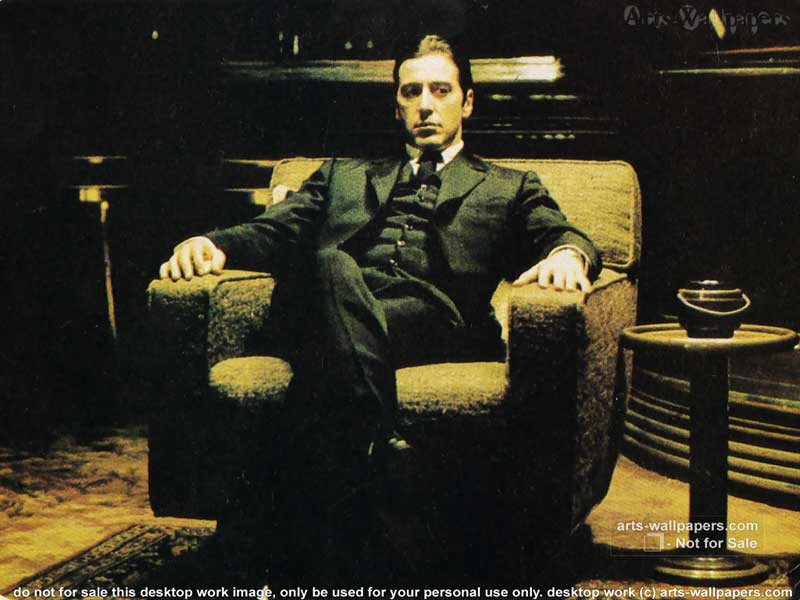

It’s a moot point whether Coppola intended this, but the ethical contrast between Vito Corleone (Brando) as an earthy, charismatic gentleman Mafiosi and his cold-blooded son and successor Michael (Pacino), a Machiavellian who winds up engineering the deaths of family members — a brother-in-law in the first film, a brother in the second — tends to mystify or at least detract from the degree to which both men are killers. If we’re being asked to brood about the moral and stylistic decline of the Corleones, we’re less likely to be attentive to the continuity of violence between the nostalgically depicted past and the more coarsely perceived near-present.

Both Kane and The Godfather (all three parts) qualify as what Manny Farber called White Elephant Art — the sort of studio sucker-punch that Kael was usually able to see through, until she capitulated without qualm to this particular brand of it, inviting her more uncritical fans to follow. (I may be alone in finding campy rather than profound the incongruous and multiple recurrences of Nino Rota’s omnipresent Godfather theme in Part II — performed on a church organ at the communion of Michael Corleone’s son at the beginning, and later sung as a folk ballad with guitar accompaniment in Little Italy almost half a century earlier, just before the Intermission.) If what Kael called “the Promothean spark in [Mario Puzo’s] trash” was really and truly ignited by the movie version, the Stalinist grandiosity and monumentality that made it all possible seemed to fly by her shit-detector without registering so much as a blip. And one possible reason for this, I would submit, is that she bought into its ideological underpinnings, perhaps unconsciously.

Even though Lee Strasberg’s performance as Hyman Roth in Part II represents a triumph of what Farber called Termite Art — especially in relation to the White Elephant Oscar-mongering of Brando’s cheek-stuffing masquerade, to which Strasberg offers a kind of lesson in Method simplicity and understatement — I’d still single out the original Godfather as the one worthier of its classic status. Yet it’s still always been tainted for me by the response of the New York audience to the final scene, the first time I saw this movie, at a huge theater just north of Times Square: when Michael Corleone lies to his wife Kay (Diane Keaton) about ordering the killing of his brother-in-law, they applauded and cheered. At the time I thought they were bring crass; today I’m more apt to think that they may have understood the movie better than Kael or perhaps even Coppola did.

Broadly speaking, the first Godfather is a generic gangster film with arthouse trimmings and the second is an arthouse film with generic gangster trimmings, but both blockbusters encompass masterful American adaptations and appropriations of recent Italian cinema. The first and best sequence in the first film, built around a wedding, is indebted to the remarkable, protracted ball in Visconti’s The Leopard (1963) while the stylish, nostalgic handling of period décor in the second appears to owe something to Bertolucci’s The Comformist (1971); and both would of course be diminished considerably without the catchy music drawn from Fellini’s habitual composer. The outsized success of both Godfathers helped to mark the eclipse of foreign film distribution in the U.S. for the sake of glossy American art movies, a little bit before Woody Allen’s (and Martin Scorsese’s and Paul Schrader’s) mining of similar fields started to take hold.

I’m certainly not claiming that Godfathers I and II lack moral ambiguity and nuance and that cherished hits necessarily lack such qualities. Lambert made a very good case for those qualities in Gone with the Wind, though I think he went overboard when he claimed — after conceding that “Thirty years will have to pass before we can know if The Godfather’s appeal is momentary or lasting” — that, unlike its predecessor [Gone with the Wind], “the involvement [that The Godfather] demands never rises above the level of sensation, since its impact lies in showing the organization of violence, painstakingly detailed.” Surely the complex irony milked out of the interfacing of family values, capitalism, and remorseless murder — a kind of irony shared with the much greater Monsieur Verdoux and Psycho — also has a great deal to do with the dynamic impact of the first two Godfathers. But I don’t think Chaplin’s film or Hitchcock’s encourages any of the same complacency, which in the case of Coppola’s films amounts to a kind of political defeatism: in both Godfathers, Michael can’t break away from his awful family heritage of obligation, vengeance, and crime, including murder. Presumably neither can we when we accept his resignation. But there’s nothing remotely noble about this resignation, Shakespearean or otherwise; it’s a cowardly form of pathos, and one which Americans have been living with on an intimate basis for the past eight years.