From the Chicago Reader (May 29, 1992). . — J.R.

A TALE OF THE WIND

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan

Written by Loridan, Ivens, and Elisabeth D.

With Ivens, Loridan, Han Zenxiang, Liu Zhuang, Wang Delong, Wang Hong, Fu Dalin, Liu Guillian, Chen Zhijian, Zou Qiaoyu, and Paul Sergent.

The Old Man, the hero of this tale, was born at the end of the last century, in a country where man has always striven to tame the sea and harness the wind. Camera in hand, he has traversed the 20th century in the midst of the stormy history of our time. In the evening of his life, at age 90, having survived the various wars and struggles that he filmed, the old filmmaker sets off for China. He has embarked on a mad project: to capture the invisible image of the wind.”

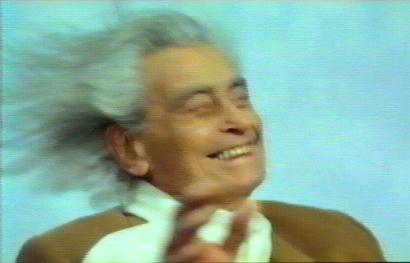

That’s my translation of the French opening title of A Tale of the Wind. It follows the credits, which accompany shots of a plane flying through the clouds and Michel Portal’s primitive-modern jazz score for woodwinds and percussion. After the opening passage the giant blades of a Dutch windmill fill the screen, followed by shots of a little boy in an aviator suit on a windswept lawn, apparently preparing to fly away on a small plane to China, calling to his mother. Finally we see the filmmaker, Joris Ivens, at age 90, sitting on a simple wooden chair in the middle of a vast Chinese desert, with a Chinese film and sound crew close at hand, waiting for the wind to arrive.

It’s been four years since this prophetic and poetic masterwork was made, and it’s just arriving in Chicago. But I wonder if we’re ready for it even now. For starters, what do we know about Joris Ivens? Although he’s generally considered to be one of only a handful of truly great documentary filmmakers, history and politics have conspired to make most of his work unavailable and unknown in this country. I suppose some would argue that this was partly Ivens’s fault — because he had the bad taste to become a communist filmmaker, and to work for much of his life in communist countries as opposed to the “free world.” Unfortunately, the freedoms granted in our “free world” haven’t yet included the opportunity to see most of Ivens’s work. He’s made more than 60 films, including antifascist work, work supporting Indonesian independence (which led to the withdrawal of his Dutch passport), and work in collaboration with Ernest Hemingway, Jacques Prevert, Gerard Philipe, Lewis Milestone, Frank Capra, Jean-Luc Godard, William Klein, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda (the last five worked with him on the 1967 sketch film Far From Vietnam). He died during the early summer of 1989, just before most of the communist world in the West collapsed.

As critic David Thomson once put it, Ivens “is like one of those long-serving suitcases held together by the labels of a lifetime’s travel,” and his lifetime’s travel virtually constitutes a 20th-century history of socialist aspirations. Born in 1898 to a Dutch family heavily involved in still photography, he fought in World War I, became a student radical in Germany, managed his father’s camera shops in Amsterdam, and made his first professional films, The Bridge and Rain, around the age of 30. Judging by the international reputation of these two films and of Philips-Radio (1931) — the last, his first sound film, is the only early Ivens work I’ve seen — he comes from that heroic period in filmmaking when radical leftism, avant-gardism, abstraction, and formalism were wholly compatible and even complementary traits.

Thanks to the impact of his early work, Ivens was invited by Vsevolod Pudovkin to make films in the Soviet Union, where he was the house guest of Sergei Eisenstein. That wasn’t the only country Ivens was to work in, however; his subsequent subjects in the 30s included Belgian coal miners (Borinage), the Spanish Civil War (The Spanish Earth), and the Japanese invasion of China (The 400 Million); then came bouts of work in the U.S. (1936, 1939-’42, 1944-’45), Canada (1942-’43), and Australia (1945-’46). After the House Un-American Activities Committee identified him as a communist during the witch-hunts, he was no longer welcome to live or work in the States and made his documentaries in Prague, Warsaw, Berlin, and Paris; then came work in China (1958), Italy (1959), Mali (1960), Cuba (1961), Chile (1962-’64), the Netherlands (1964), and Vietnam and Laos (1965, 1967-’69). His longest stint in one place was probably in China between 1971 and 1976, when he codirected the 12-hour, 14-part How Yukong Moved the Mountains with French filmmaker Marceline Loridan; otherwise, it appears that his main home bases in Europe were Paris and, more briefly (1979-’83), Florence.

Loridan, 30 years his junior and a Jew who spent most of her teens working for the French Resistance, was his collaborator and companion from 1963 on. She is perhaps best known for her appearance as one of the key characters and documentary subjects in Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer, filmed in Paris in 1959-’60. Unlike Ivens, she makes only a fleeting appearance in A Tale of the Wind (in a satirical section about Chinese government bureaucracy), but she is credited as codirector (with Ivens) and cowriter (with Ivens and a young Parisian identified in the credits only as “Elisabeth D”). Judging from a lengthy conversation I had with her at the Rotterdam film festival in 1989, I think there is reason to believe she may have scripted most of the film. (Ivens himself stated in an interview that “Marceline was the one who found the wind theme.”) The fact that the film is essentially collaborative, in any case, is only part of the means by which it confounds many received ideas we have about artistic process and genre. Simultaneously a documentary and a fantasy for all 78 minutes of its running time, A Tale of the Wind is also a sublime auteurist statement starring its auteur, largely created, it would seem, by his lover.

When the earth breathes, one calls it the wind. –Chinese proverb

At the end of the 20th century, I believe in magic. It isn’t only science that works wonders. –Joris Ivens, A Tale of the Wind

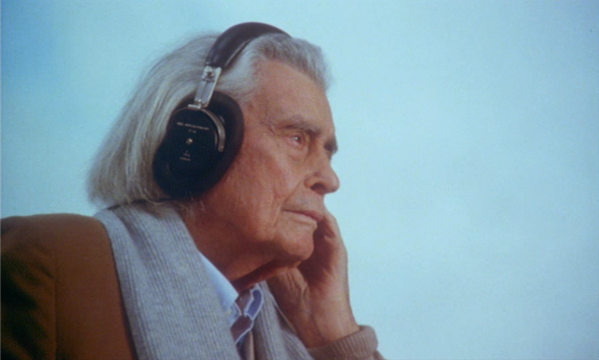

Early in the film, we learn that Ivens suffers from asthma and has only one lung. Indeed, changes in his health while the film was being made became part of its texture and substance, and in some respects Ivens’s project to film the wind, which forms the principal narrative thread, is a search for the wellsprings of life itself.

It is also a route into the riddle of China, and Ivens explores this riddle in terms of the past and the future as well as the present. Like Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Horse Thief, A Tale of the Wind is a film made for the 21st century, and Ivens and Loridan implicitly seem to be saying that if the 20th century fundamentally belonged to the West, the 21st century already seems to belong to the East. This is not a message likely to flatter the egos of jingoistic Westerners — which probably helps to explain why, in spite of its major importance, A Tale of the Wind has not fared especially well in the Western world (it has yet to acquire a distributor in either this country or England, for instance) — but I happen to find the message quite persuasive. It even serves to account for why, in spite of this movie’s monumentality and importance as a statement, it is light rather than heavy, playfully modest and charming in its overall address rather than pretentious and ponderous. (Some of the loveliest two-tiered compositions in the film, which juxtapose technology in the foreground with timeless nature in the background, recall certain comic and utopian deep-focus shots of Raul Ruiz.) To put it crudely, the oedipal and Faustian neuroses that have so much to do with the West’s tortured, ego-infested notions of cultural achievement find little room for expression here. The film is clearly addressed to the West and not to China (Ivens, incidentally, speaks to the Chinese in French and English, and they mainly respond in Mandarin), and the overall message is to listen to all that China has to say.

The film presents us with many interlocking and interfacing histories, including the history of cinema and Ivens’s own life. The film includes clips from two early Ivens works — The Breakers (identified by Ivens as “my first love story, in 1930”) and The 400 Million — and from Georges Méliès’s Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon, 1902), made and released when Ivens was four years old, which means when he and the cinema were both in their infancy. The brief sequence we see from the Méliès film ends with a rocket from earth hitting the Man in the Moon in the eye; the moon’s mouth opens, and out of it, to our amazement, comes Ivens himself, strolling across the moon’s black-and-white surface and encountering a Chinese woman — the legendary Ch’ang E., who fled to the moon after stealing her husband’s pills of immortality. Descending from her crescent-shaped perch in the sky, she asks Ivens, “Aren’t you sad to see your white hair?” This comes not long after the film pays its own separate tributes to Chinese poetry and to Méliès. The first is metaphorical: Ivens listens on earphones to Chinese reports of storms and tornadoes in France, Great Britain, Texas, Japan, New Zealand, and Mexico followed by temperate Chinese weather reports. The second comes when the film makes beautiful use of a Mélièsian tableau to illustrate (in color) a Chinese legend point by point: “Ten suns were threatening to burn the earth and his majesty sent Hou Yi to fire nine arrows; nine suns died: the earth and mankind were saved.”

The history of China includes everything from sweeping helicopter vistas of the Great Wall to a semisatirical depiction of the Cultural Revolution as a series of circus acts and scenes of village life staged inside a film studio that Ivens casually strolls through; he witnesses everything from acrobatics to a political harangue to a little girls’ glee club intoning bloodthirsty propaganda in treacly tones. An impish Chinese demon and dancer in white greasepaint, at once benign and mischievous — periodically crossing Ivens’s path shedding banana peels and unfurling a picture of a dragon — seems to represent another aspect of Chinese history, and when Ivens is seen leaving the film studio, the impish mask he’s wearing reveals that he has briefly become the clownish monkey himself. The filmmakers’ exquisite sense of wonder is conveyed to us shot by shot and incident by incident, in an unbroken series of epiphanies, and the handsome, elfin, white-haired Ivens becomes the string that holds it all together.

Both poetic essay and meditative fiction, A Tale of the Wind has certain affinities with movies as different as Jean Cocteau’s The Testament of Orpheus, Chris Marker’s Sans soleil, and Souleymane Cissé’s Brightness, but it is too proud to owe its vision to any source beyond Ivens’s own far-reaching experience and research. Part of the film’s inspired thesis appears to be that cinema and history, fantasy and documentary, have a lot to teach each other.

Ivens’s travels along the Great Wall — “built 200 years before Christ by the Emperor Qin Shi Huang,” reads a printed title — eventually lead him to the site of the army of 7,000 clay warriors that guard that emperor’s tomb. After he and Loridan seek in vain for eight days to receive official permission to film this site however they see fit (“I’m fighting for my art and for my freedom of expression,” Ivens declares to the authorities) and are told they can only film for a total of ten minutes from eight approved camera angles, Ivens finally gives up, purchases models of the warrior statues, and winds up creating yet another Melies sequence of his own — one of the most stunning, magical, and beautiful in the film.

Still later, trekking across mountains and desert with his camera and sound crew in search of the elusive wind, he is told by a Chinese peasant woman, perhaps a witch, that she can draw a magic figure in the sand that will beckon the wind out of hiding. She needs, however, two electric fans, and these are promptly sent for and delivered to the site by a camel, leading to the ecstatic miracle that forms the film’s climax. Like the Meliesian warrior sequence, it is yet another instance of folklore and technology, archaeology and fantasy being brought into a sublime proximity, even a communication with each another. It is Joris Ivens’s message to — or is it from? — the 21st century, if only we are brave and alert enough to listen.