Written for FIPRESCI, specifically for their web site,from Seattle. –J.R.

The Undermining of Intimacy: Home and Everyone Else

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

As different as they are in other respects, one interesting facet shared by two tragicomic European features included in the New Directors Showcase at the Seattle International Film Festival, Ursula Meier’s Home (2008) and Maren Ade’s Alle Anderen (Everyone Else, 2009), is that they both show the gradual deterioration of intimate relationships that starts to occur between or among individuals in isolation from “everyone else”, after they start to become less isolated. In both cases, contact with the outside world seems to operate as a kind of contamination, although the possibility is posed in each case that the

sickness is already present from the outset, but needs the objectification provided by the outside world in order to become fully evident.

Meier’s Home, a second feature, introduces us to an eccentric but lovingly and happily close-knit family living in the country next to an unfinished superhighway — mother (Isabelle Huppert), father (Olivier Gourmet), older daughter (Adéläide Leroux), younger daughter (Madeleine Budd), and son (Kacey Mottet Klein) — who are gradually driven bonkers by the sound, pollution, and lack of privacy brought by passing vehicles once the superhighway opens. More precisely, all of the family members seem to go to pieces except for the older daughter, who manages to escape relatively early.

One could perhaps criticize Home for being a bit too simplistic and even programmatic in charting this family’s deterioration (characteristically, the older daughter’s disappearance is never explained clearly in terms of motivation and is basically introduced like a theorem), but there are none the less various ambiguities about the characters and their interrelationships that are difficult to resolve. The older daughter, who seems relatively detached and aloof, may be “saner” than her parents and siblings, but it takes us most of the duration of the film to discover this fact, highlighting the degree to which sanity is a relative rather than absolute quality, a quality determined by context.

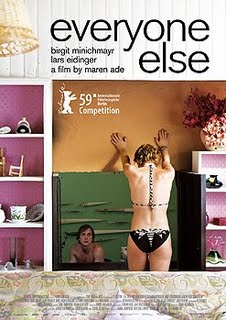

Ade’s Everyone Else, a second feature, has a much smaller cast of characters — mainly a single couple, Gitti (Birgit Minichmayr) and Chris (Lars Eidinger), who are vacationing in Chris’s mother’s house in Sardinia — but, here again, their deterioration, at least as a couple, seems brought about largely through their contacts with the outside world, principally with a second couple. The film’s overall dramatic trajectory, including the gradual alienation of Gitti from Chris, can be traced between two occasions when Gitti falls into a swimming pool and “plays dead” — initially as a comic performance given to Chris’s young niece, and subsequently as a prank-like incident precipitated by the other couple. In this case, the overall psychological development, far from being simplistic or programmatic, is characterized by a great deal of ambiguity regarding the identities and feelings of both Gitti and Chris. A major issue here appears to be how much Gitti and/or Chris are making up their own rules, in flight from bourgeois conventions, and how much they’re merely pretending to do so. As in Home, our inability to pass final judgment on the characters becomes the basis of what makes them interesting.