From the Chicago Reader (July 21, 2000). My thanks to my editor on this piece, Kitry Krause, for (among many other things) coming up with my title. — J.R.

Time Regained ***

Directed by Raul Ruiz

Written by Gilles Taurand and Ruiz

With Marcello Mazzarella, Catherine Deneuve, Emmanuelle Béart, Vincent Perez, John Malkovich, Pascal Greggory, Marie-France Pisier, Christian Vadim, Arielle Dombasle, Chiara Mastroianni, and the voice of Patrice Chéreau.

[A few years ago], I refused to direct Remembrance of Things Past. I wrote to the woman producer [Nicole Stéphane] that no real filmmaker would allow himself to squeeze the madeleine as though it were a lemon and in my opinion only a film butcher would have the nerve to put Proust through the mincer.

A few weeks later she obtained the agreement of the Verdurin salon, that is to say, René Clement. Come to think of it, is Proust burning in [the book-burning fires of my film] Fahrenheit 451? No, but this omission will soon be corrected.

— François Truffaut, “The Journal of Fahrenheit 451” (1966)

I read Remembrance of Things Past all the way through more than 35 years ago, shortly before Truffaut registered his scorn about the very notion of a film version (Stéphane eventually got the film made in 1984, Volker Schlšndorff’s dispensable Swann in Love). Yet I still remember my encounter with Proust as sharply as if I’d been visiting a foreign country for the first time. It was a complex engagement that made me wiser, because, as Alain de Botton recently demonstrated in How Proust Can Change Your Life, Remembrance of Things Past is the ultimate self-help book, bristling with useful advice and information. It also made me more foolish, because Proust’s neurotic fixations about falling in love and its attendant agonies were so convincing that I probably exaggerated my own when I fell in love for the first time soon afterward.

I read the novel during an extended college break, averaging about 100 pages a day, with Edmund Wilson’s wonderful Proust chapter in Axel’s Castle as my principal guide. Not stretching my reading of the novel over several months undoubtedly enhanced the experience, because Proust’s strategically plotted surprises about his characters, in which people often turn out to be much different from what we suppose, are bound to be less dramatic if we have enough time to forget our first impressions.

In total, I must have spent the equivalent of two days reading. Raul Ruiz’s Time Regained — a brilliant and original 165-minute adaptation playing this week at the Music Box — sensibly tries to limit itself to the last of the novel’s seven sections, Le temps retrouve, referring back to material in previous parts only when necessary. Yet anyone who approaches Time Regained thinking it might capture the essence of the greatest novel of the 20th century in roughly one-17th the time it took me to read it is indulging in an orgy of self-deception. I couldn’t recommend the film to anybody in search of such a digest or as any sort of replacement for the original. For starters, most of the surprises about characters are reduced to footnotes rather than incorporated into the main text. For better and for worse, Ruiz’s version is closer to a game than an adventure — not so much a lesson about life as an elaborate piece of playfulness.

Ruiz, I should add, is a friend, and one thing that’s made me skeptical about his project from the outset — it became an obsession of his years ago — is that compromises of various kinds were virtually inscribed in its conception. The desire to make a star-studded blockbuster has always seemed a bit contrary to his nature and his talent for throwaway invention. Only last month he admitted to me that he had had to cut about 45 minutes prior to the film’s 1999 Cannes premiere — two-thirds of which he accepted without qualm, one-third of which he regretted because it made the film more difficult to follow (he especially regretted the loss of some material relating to the character of Morel). He originally hoped to cast, among others, Michel Piccoli as Charlus and Bernadette Lafont as Francoise, and when at one stage executives tried to impose Gerard Dépardieu as Charlus — blockbuster thinking with a vengeance — he told me that under such conditions he’d rather not make the movie at all.

Back in the 60s, my own ideal casting for Charlus was Peter Sellers, who’d recently starred in Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita, and despite the resourcefulness of John Malkovich in the part, dubbed on occasion by someone else, I miss the comic extravagance of Proust’s character as well as the comic violence sometimes associated with him. The same applies to Marie-France Pisier’s otherwise highly resourceful Madame Verdurin. I’m reminded of Edmund Wilson’s invocation of Dickens in relation to these two characters, in particular “Mme. Verdurin’s dislocating her jaw through laughing at one of Cottard’s jokes” and “the furious smashing by the narrator of Charlus’s hat and the latter’s calm substitution of another hat in its place.” Generally, imperfect casting and the need to prune the text cause virtually all of Proust’s characters to lose some of their richness. (One minor piece of casting is a sly joke — Alain Robbe-Grillet as Goncourt.)

Ruiz, who only recently became a French citizen, remains a footloose Chilean intellectual. His oeuvre has been achieved largely through taking on absurdly grandiose challenges — first to make 100 films (a goal he achieved years ago, at least if videos count as films), then to make more films/videos than all other Chilean filmmakers combined. He has obviously taken on Proust as one more macho dare, and even if he’s met the challenge with more ingenuity and wit than one might have thought possible, one can still question whether it was ever worth thinking about. (Admittedly, Eisenstein dreamed of doing Marx’s Das Kapital, yet that film project never went beyond a few pages of notes, which surely protects its glamour as High Concept.) Ruiz has never been much of a hustler, so it shouldn’t be too surprising that what I regard as his greatest work — his 1985 Portuguese miniseries, Manuel on the Isle of Wonders, which is only 15 minutes shorter than Time Regained — is perhaps the one that’s hardest to see (to the best of my knowledge it survives only in a French-dubbed version that showed with English subtitles on Australian television many years ago), whereas some of his movies that have had the widest American exposure — The Golden Boat (1989) and more recently Shattered Image (1997) — are among his least accomplished and interesting.

Even if it lacks the emotional power of Manuel, Time Regained is a lot closer to Ruiz’s best work than it is to his worst. Yet apart from the personal challenge it represented, I’m not convinced that it’s a film that anyone had to make. It will undoubtedly encourage some people to read or reread the book, but it will also provide many others an excuse for never reading it at all. In any case, is it possible to separate its praiseworthy value from its value as a glossy, high-priced cultural object — the sort of position awarded most Merchant-Ivory productions and comparable upscale consumerist literary adaptations such as The Wings of the Dove? The argument that Ruiz manages to subvert the interior-decoration syndrome represented by these movies is undermined by the fact that it caters to essentially the same crowd, sometimes even in the same way. (A good example of Ruiz exploiting this syndrome with some charm — emblematic of the film’s overall flair for selecting pungent period details — is a passing allusion to the Theatrophone service, which allowed wealthy stay-at-homes to hear live music through a telephone receiver held up during a concert. According to Edmund White’s recent book on Proust in the Penguin Lives series, Proust became a subscriber to this service in 1911 and listened to Wagner and Debussy in this fashion.)

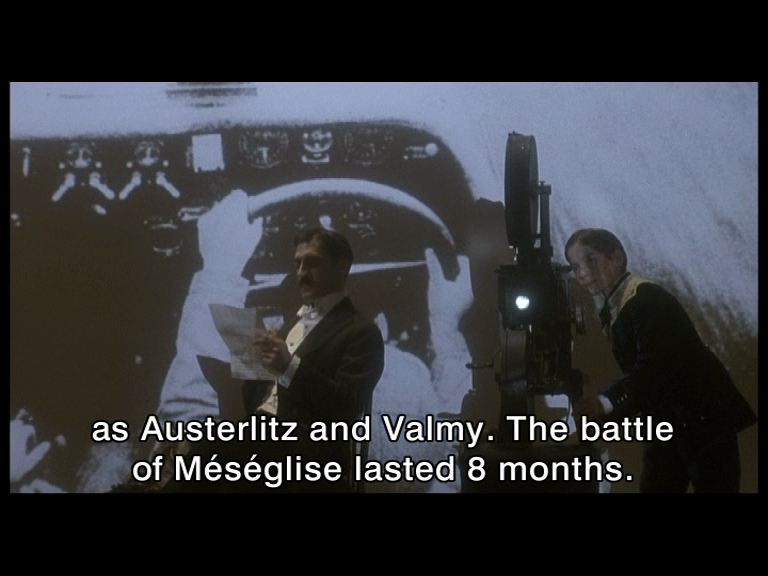

Perhaps the best justification for this movie is the old chestnut that Proust is profoundly cinematic, an idea the film doesn’t so much prove as endlessly play with. Ever since I first became interested in film criticism I’ve been fascinated by a 1946 article by Jacques Bourgeois — published in La revue du cinéma, a postwar precursor of Cahiers du cinéma — arguing that Proust’s novelistic techniques anticipate those of cinema in general and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane in particular. One of Bourgeois’ best ideas is that Proust’s labyrinthine sentences proceed like camera movements — an insight whose truth becomes more apparent if one compares Proust’s long sentences with those of, say, Henry James or William Faulkner, which bear no apparent relation to pans, tracks, or cranes. Welles is of course Ruiz’s avowed master, and a good deal of Time Regained seems to proceed like an extension of Bourgeois’ stylistic comparison, with not only camera movements but the gliding displacements of objects and characters re-creating some of the complex, winding journeys of Proust’s sentences. At a climactic concert at a party, rows of listeners can be seen gliding off in separate directions as if on separate mind journeys, and in a much earlier surreal sequence featuring newsreel war footage in a cafe, the narrator, reading a letter, can be seen rising with his chair like a film director seated on a crane, all the way to the top of the room, where he encounters his own childhood self running a projector — an image that might be traced, like much else, to one of Proust’s extended descriptive passages.

The problem is, even if many of Proust’s long sentences are experienced as “movements” of this kind — and the musical meaning of the term also seems apt — this still doesn’t take one very far into Proust’s theories about the difference between involuntarily reexperiencing an instant of the past (which is what happens when the narrator bites into the madeleine dipped in tea or stubs his toe in Venice) and deliberately exploring the past through memory. Ruiz doesn’t exactly avoid this topic, but he treats it as an occasion for another jokey representation rather than for a serious discussion of the topic — which is no surprise given his cinematic options. It’s at moments like these when the stuffy old professors who insist that movies can never capture the density of literature seem absolutely right; in this case they can’t even capture the same sensual immediacy. And some of the same strictures apply to Proust’s subtle notations of the powerful investments of imagination and emotion in particular places.

When some of this film’s detractors — including Roger Shattuck in his recently published Proust’s Way — complain that people who haven’t read the novel will find it incomprehensible, I can only reply that I regard this partly as a plus. One of the deadliest things about most of this summer’s commercial movies is their absolute legibility and transparency, their total lack of mystery. I’m reminded of Luc Moullet’s spirited defense in Trafic of Ruiz’s 1987 adaptation of Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl, surely one of his greatest films: Moullet passionately avows, “I’ve seen The Blind Owl seven times, and I know a little less about the film with each viewing.” Both times that I saw Time Regained — a year apart, with and without subtitles — I got lost more than once and basically liked the movie more as a consequence. One doesn’t get lost in Proust’s novel, whose overall lucidity is an abiding strength, but obscurity and unsolved mystery are central to what I like most about Ruiz — and about Hedayat’s novel, for that matter, which Ruiz adapts a lot more freely than he does Proust.

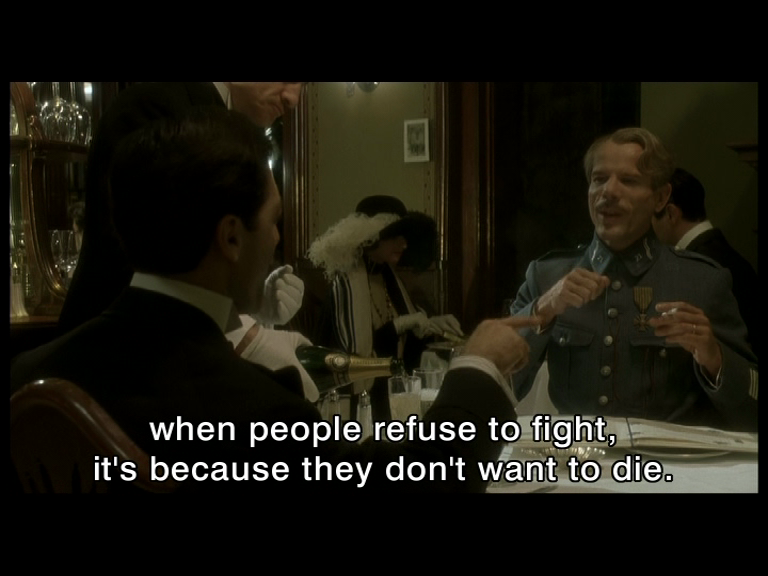

My memories of reading Proust’s novel depend largely on the first two sections — Swann’s Way and Within a Budding Grove — serving as lenses for the final five, and it’s possible that some of my difficulties with the movie stem from its use of the last section as a lens for the preceding six. It’s a logical way to cram in a lot of material, and it has the particular merit of foregrounding the importance of World War I in all the late episodes in the novel — thereby making possible what may be Ruiz’s best realized and most physical single scene, the audible chewing of a steak by Robert de Saint-Loup (Pascal Greggory) in a posh restaurant with Marcel while he’s temporarily back from the trenches. But it’s still a far cry from the experience of reading most of the novel.

One facet of the interior-decoration syndrome that Ruiz seems fully ready to buy into is the presence of Proust himself — not merely “Marcel,” his narrator and perfunctory stand-in — as a high-priced object in the proceedings, reminding me of the most vulgar literary adaptations (e.g., Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man and Mishima, both of which regard artistic work almost exclusively as Freudian symptoms). The film opens with Proust dictating Remembrance of Things Past, not with Marcel visiting Tansonville, which is how the book Time Regained begins. This is where the so-called cinematic properties of the novel start to break down and the rather different dictates of movie spectacle take over. Yet at the same time Ruiz goes to considerable lengths to disembody both Proust and Marcel by creating an ambiguous zone between them that’s inhabited by no less than six actors: Marcello Mazzarella as “Marcel,” André Engel as “old Marcel,” Jean Leger as the actor who dubs Engel, Georges du Fresne (star of the Belgian film My Life in Pink) as “Marcel as a child,” Pierre Mignard as “Marcel as an adolescent,” and finally director and actor Patrice Chereau as “the voice of Marcel Proust.” Maybe most of the character revelations figure as footnotes, but the construction of the characters is still carried out in separate layers — the same way that Marcel Proust’s cork-lined bedroom is introduced to us, displaced objects and all. And by having Proust acquaint us with each of his major characters via photographs seen through a magnifying glass — a method recalling the way we’re introduced to the major characters at the beginning of some of Louis Feuillade’s serials, made just after the war — Ruiz in a way is only capitalizing on the confusing relation of autobiography to fiction that Proust’s novel already has in abundance.

One way to illustrate how close to and how far from the original Ruiz is would be to compare one early paragraph with one early sequence. Here is Proust’s paragraph, as translated by Andreas Mayor. (This was the opening paragraph of Le temps retrouvé when this translation was still called The Past Recaptured, before the French Pleiade editors and Terence Kilmartin’s 1982 Vintage edition put the beginning of the Tansonville episode that formerly appeared at the end of the previous section before it.)

“All day long, in that slightly too countrified house which seemed no more than a place for a rest between walks or during a sudden downpour, one of those houses in which all the sitting-rooms look like arbors and, on the wallpaper in the bedrooms, here the roses from the garden, there the birds from the trees outside join you and keep you company, isolated from the world — for it was old wallpaper on which every rose was so distinct that, had it been alive, you could have picked it, every bird you could have put in a cage and tamed, quite different from those grandiose bedroom decorations of today where, on a silver background, all the apple trees of Normandy display their outlines in the Japanese style to hallucinate the hours you spend in bed — all day long I remained in my room which looked over the fine greenery of the park and the lilacs at the entrance, over the green leaves of the tall trees by the edge of the lake, sparkling in the sun, and the forest of Meseglise. Yet I looked at all this with pleasure only because I said to myself: ‘How nice to be able to see so much greenery from my bedroom window,’ until the moment when, in the vast verdant picture, I recognized, painted in a contrasting dark blue simply because it was further away, the steeple of Combray church. Not a representation of the steeple, but the steeple itself, which, putting in visible form a distance of miles and of years, had come, intruding its discordant tone into the midst of the luminous verdure — a tone so colorless that it seemed little more than a preliminary sketch — and engraved itself upon my windowpane. And if I left my room for a moment, I saw at the end of the corridor, in a little sitting-room which faced in another direction, what seemed to be a band of scarlet — for this room was hung with a plain silk, but a red one, ready to burst into flames if a ray of sun fell upon it.”

The film’s corresponding sequence, which lasts only a few seconds, gives us both the roses and the birds on the wallpaper — the former magically interfacing with the latter — before moving slowly toward the half-open window in Marcel’s bedroom, where the trees in the garden seem to advance as well as retreat, until the blue Combray church steeple in the distance suddenly intrudes in the middle of the pan, playing still further with our confused sense of perspective by conveying some abstract sense of miles, though no sense of years. Meanwhile, the narrator’s voice says, “All day long, in that slightly too countrified house which seemed no more than a place for a rest between walks or during a sudden downpour […] where, on a silver background, all the apple trees of Normandy display their outlines in the Japanese style to hallucinate the hours you spend in bed — all day long I remained in my room which looked over the fine greenery of the park and the lilacs at the entrance, over the green leaves of the tall trees by the edge of the lake, sparkling in the sun, and the forest of Meseglise. Yet I looked at all this with pleasure only because I said to myself: ‘How nice to be able to see so much greenery from my bedroom window,’ until the moment when, in the vast verdant picture, I recognized, painted in a contrasting dark blue simply because it was further away, the steeple of Combray church.”

The original passage in Proust reeks of the narrator’s sickbed and the swooning sensations of the outside world that only intensify his labored breathing and his vertigo. By contrast, the sequence in Ruiz is like a box of toys without a child to play with them — it feels virtually uninhabited, moving in effect from an experiment in optics (two merging kinds of wallpaper) to a detail in a pop-up book (the Combray church steeple) to a traverse of a green space resembling part of a model train set (a recurring motif in many earlier Ruiz films, including Manuel). A great deal of Proust’s prose gets recited — some of it conjuring up images that complement rather than echo the images we see — but the sinuous musical experience of reading has been replaced by the more clustered and playful effects of shifting lights and perspectives, with the narrator serving more as a vehicle for the effects than as a character.

In short, Ruiz offers both a beautiful reduction and a translation that substantially shifts the meaning and emphasis of the original. It deals adroitly with those aspects of reading Proust that are like taking an exquisite theme-park ride, but can’t do much with elements that elude that experience. And characteristically, Ruiz’s taste for surrealism is allowed to overtake the novel’s depictions of shaped experience in many of the film’s most striking images, such as a crowd of upturned top hats covering the floor of an ornate antechamber.

Another recent, idiosyncratic “reading” of Proust, in no sense toylike, is Chantal Akerman’s La captive, which premiered in Cannes in May and which I managed to see last month at the Pesaro film festival. It’s not clear when we can hope to see it in the U.S., because it seems most American critics at Cannes didn’t like it. But it has a purity and maturity matched by few of Akerman’s other fiction films, apart from Jeanne Dielman, and its ambiguous handling of period — which sets all its action in the present while suggesting the opulent past throughout — evokes Robert Bresson’s Les dames du Bois de Boulogne. Inspired by rather than adapted from the story of Marcel and Albertine that comprises the novel’s fifth and sixth sections, La prisonnière (The Captive) and Albertine disparue (The Fugitive), it critiques the original by giving us much more of Albertine’s view of Marcel’s jealousy than Proust did. In this respect, Proust is Akerman’s launching pad but not her destination.

It’s questionable whether Ruiz achieves any of the same independence from his source. But unlike Joseph Strick’s almost completely (and deservedly) forgotten 1967 film adaptation of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Time Regained can’t be accused of simple reductiveness; it doesn’t sentimentalize any of the material or insult the viewer, and it can’t be accused of turning the novel into a simple object. It’s a complex reduction and a playful one — inviting the spectator who knows Proust to engage in a dialogue with it and the uninitiated spectator to get lost in the swirling patterns of an enchanting and highly entertaining trailer.