From the July 1982 issue of Omni; reprinted in Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues (2018). As with all the other commissioned pieces I wrote for the Arts section of that magazine, this originally ran without a title; I’ve also done a light edit on this version. Another version of this article appeared in Cahiers du Cinema, with a different title (if memory serves, this was called “Beware of Imitations”).

While I was living in Europe in the 70s, I managed to watch portions of the shooting of films by Robert Bresson (Four Nights of a Dreamer), Alain Resnais (Stavisky…), and Jacques Rivette (Duelle and Noroit), but my trip to Alaska and British Columbia in December 1981 to watch a little bit of the shooting of John Carpenter’s The Thing was surely my most elaborate on-location visit, even though what I actually saw was much briefer in this case — hardly any more than an hour or two at most. And I didn’t even get to speak to Carpenter during my visit; absurdly enough, by arrangement with the film’s publicist, the interview in this piece was conducted over the phone several days later, with Carpenter calling me from Hollywood, after I returned to Hoboken, making the cassette recorder I had carried on my trip completely unnecessary and some portions of this piece necessarily deceitful. I received this assignment almost immediately after I was fired from my only steady source of income at the time — a weekly stint of reviewing movies and books for the Soho News — which somehow added to my overall sense of incongruity about the entire experience. — J.R.

We all know what the Klondike is: a remote frontier, raging with blizzards, where W.C. Fields can look out the door of his log cabin, dryly remark, “T’ain’t a fit night out for man nor beast,” and then get a fistful of snow dutifully thrown at his kisser. Such, at any rate, was the image conjured up in my own mind when I discovered that I was flying all the way up to Hyder, Alaska last December, to watch one of the final days of exterior location shooting on John Carpenter’s The Thing — a remake of a 1951 science fiction chiller — set somewhere in the vicinity of the Arctic Circle and budgeted at $11.5 million. [2020: Barry Moore, a reader from Austin, has pointed out that the story’s location is actually Antarctica.]

Simply in order to get to this spot, I had to fly from New York City to Seattle for a night’s stopover, continue on Alaskan Airlines up to Katchikan, and then proceed in a private, amphibian, four-seater plane — 6,000 feet over narrow, forbidding valleys edged with snowy peaks, for an hour of spectacular vertigo — which eventually docked in Hyder. From there, it was another hour up a twisting, one-way mountain road to the ultrascenic location — an Air Force compound where Carpenter, his all-male cast, and his crew had set up camp.

For all those familiar with the scary, low-budget original — produced and supervised by the late Howard Hawks and directed by his sometime editor Christian Nyby — the movie is a model of talky, fast-paced, macho group interaction, bearing all the earmarks of Hawks’s own films as a director, such as Only Angels Have Wings and His Girl Friday. Critic Manny Farber described it at the time as a “well-cast story, as raw and ferocious as Hawk’s Scarface, about a battle of wits near the North Pole between a screaming banshee of a vegetable and an air-force crew that jabbers away as sharply and sporadically as Jimmy Cagney moves.” Carpenter is a devoted Hawks fan in his own right. He included clips of the original film version of The Thing (shown on a TV screen) in his hit Halloween, and he was already featuring lengthy tributes to Hawks’s Rio Bravo in his earlier Assault on Precinct 13. It would seem you’d have a faithful adaptation on your hands. (The script is by Bill Lancaster, son of Burt, whose principal previous credit is The Bad News Bears.) Yet the funny thing about Carpenter’s remake is that it is faithful, but not to Hawks. Carpenter’s object of fidelity is the 1938 story that the Hawks movie was loosely based on — “Who Goes There?”, by John W. Campbell, Jr. — which Hawks, Nyby, and veteran scriptwriter Charles Lederer overhauled without any compunction.

“The original movie has always been one of my favorites,” Carpenter confessed to me at one point. For a lot of reasons, like its mood and style. And at the time it came out, it was very powerful — at least for me, as a young kid — and very frightening. In Halloween, I felt that the way the shape was portrayed was somewhat like the way the monster from outer space in The Thing was portrayed. You don’t really see it too clearly.

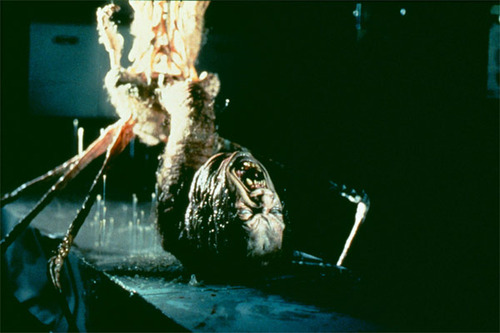

“In terms of remaking the film, that’s a different issue,” Carpenter continued. “In addition, I’ve always admired the story that The Thing came from. It’s an entirely different animal, and I’ve always wanted to remake — or, actually, make — that short story basically the way it was written.” Unlike the Frankenstein monsterlike, self-regenerating, eight-foot-tall vegetable in the 1951 movie, played by James Arness, the monster in Campbell’s version sports three eyes, “four tentaclelike arms” (each of which has a “seven- tentacled hand”), blazing blue hair “crawling like worms,” and rubbery flesh, and it’s only four feet tall. Its true horror, though, is less its appearance than its endless capacity to consume and duplicate living matter of all kinds, thereby threatening to conquer the whole planet.

A “problem” story of the sort that John Campbell was famous for developing (as an editor of Astounding Stories), “Who Goes There?” shares with the Hawks film a strong sense of human interaction. According to another celebrated science-fiction writer, the late C.M. Kornbluth, it isn’t a “monster story” at all, but “a story about maintaining integrity, working together, using brains and courage to solve the problems of survival in an indifferent world.”

“That’s somewhat right,” Carpenter said to me when I read him this quotation. “We emphasize another aspect of it: A group of people are confronted with this problem –that one, or more, or all of them could be the same, that is, be taken over by the Thing — and we concentrate on the amount of paranoia this produces between them. It’s about losing your identity.”

Losing your identity in the snowy wilds of Alaska seems like a simple matter as soon as you realize what you have to wear in order to get around in it, which tends to make you resemble everyone else — an insulated, bulky snowperson. (My own badge was a briefcase holding my cassette recorder, which made me feel almost as doltish as Scotty, the hapless journalist who tags along with the Air Force in the 1951 movie.) Such elaborate apparel becomes necessary, though, only when you’re up on the remote mountain where Carpenter is shooting about 4,000 feet above sea level, not far from copper and gold mines and right next to a big glacier.

Back down the mountain, in the small border town of Hyder, one proves one’s mettle otherwise, in more interior pursuits. At the Glacier Inn, you can get yourself Hyderized with Everclear, 190-proof corn liquor — free if you can down it in one gulp, the cost of staking everyone in the house to a drink if you can’t. Rather than elect for either option, I content myself with coffee laced with 100-proof Yukon Jack. “A taste born of hoary nights, when lonely men struggled to keep their fires lit and cabins warm,” says the label, although the stuff is bottled in Connecticut.

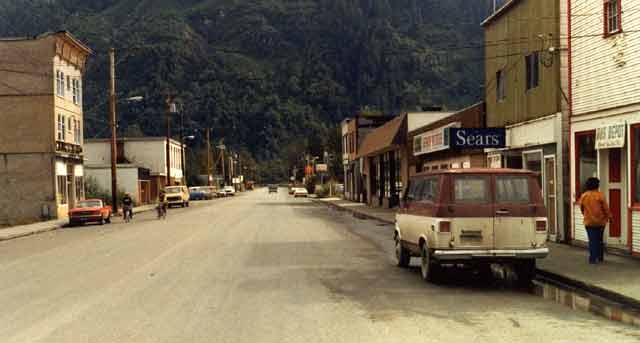

Right across the border from Hyder is the town of Stewart, in British Columbia, where I’m staying along with a goodly portion of the cast and crew. A town of about 2,500 inhabitants that was much larger during the gold-rush days, Stewart had other traffic with film units before Carpenter’s entourage arrived. Back in the early Twenties newsreel producer R.J. Surratt filmed an old-time dance at the schoolhouse and local mining activity, and much more recently Donald Sutherland, Vanessa Redgrave, and Richard Widmark came to town for location shooting on Bear Island (1979).

Now the stars are less plentiful. Only Kurt Russell, a veteran of the Disney studios who also played Snake, the lead in Carpenter’s Escape from New York, is likely to be familiar to many filmgoers. A considerable portion of The Thing‘s budget is being given over instead to elaborate special effects. Most of these have been created at Universal City Studios by an impressive team headed by Roy Arbogast (who did special mechanical effects on Close Encounters of the Third Kind), including Rob Bottin (designer of the special makeup effects in The Howling) and Oscar-winner Albert Whitlock (of Earthquake fame).

On location between takes, the publicist describes such fancy effects created there as a fireball racing down a corridor and a spinning floor inside the same snowbound compound. Here in Alaska, the main order of the day is getting Macready (Russell) to use a blowtorch to set fire to an apparently mad biologist named Blair (Wilford Brimley), then blow up Blair’s shack and a storage hut with TNT.

Featured On Photobucket

“I prefer working on a soundstage,” Carpenter admits, standing standing outside the compound exterior, a facade lined with glittering icicles, under a string of eerie blue lights. He also confesses that he misses some of the challenges inherent in low-budget shooting, where there’s less of a “tyranny of money,” and it’s clear that effects work isn’t his favorite part of filmmaking: “I didn’t like it on Dark Star, when I had sixty thousand dollars, and this is just as difficult.”

Location shooting has its worries, too. In June 1981, while doing second-unit work on the Juneau ice field, he and his crew briefly found themselves snowbound; again, while en route down the mountains in a helicopter, he got caught in a snowstorm and experienced a white-out. “I’m not enjoying myself on this location; it’s probably the hardest shoot I ever had. But so far the results have been really astonishing. They open the film up.”

In the night sequences that are filmed next, which understandably have to be done in single takes, stuntman Tony Cecere, ignited by a blowtorch, crashes through a compound wall and window and into the snow, where he staggers for several feet before dropping. Cecere is a specialist in getting roasted under see-through insulation for different movies, and this is his twenty-eighth burn in half as many months, but there’s still a nurse from Stewart on hand just in case something goes wrong. Then Macready blows Blair’s shack to bits with some dynamite — a blast loud enough to make me and much of the crew jump.

Finally the set gets cleared for the explosion of the storage hut — filmed by two cameras at 30 frames per second — which we watch from a distance, blossoming like a livid smear against the dark sky. It’s a calm evening otherwise, but you’d never know it in the scenes being shot, which are all equipped with Ritter wind machines and plastic snowflakes spilled in front of them, to ensure proper blizzard ambience.

Somewhat later Carpenter will respond to one of my queries — “Is this version of The Thing pro-science like Campbell’s story, or anti-science like Hawks’s movie?” — by asserting that he’s trying to make his version “pro-human”. “It’s better to be a human being than an imitation, or let ourselves be taken over by this creature who’s not necessarily evil, but whose nature it is to simply imitate, like a chameleon.” But as I reflect on my icy ride back down the mountain, if the characters inside the compound are experiencing an identity crisis, the same might be said of the snowflakes outside.