From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 2004).

On February 12, 2018, Ken Jacobs sent me the following email:

— J.R.

Star Spangled to Death

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Ken Jacobs

With Jack Smith, Jerry Sims, Cecilia Swan, Gib Taylor, Bill Carpenter, Laurie Taylor, Reese Haire, Bob Fleischner, Jim Enterline, and Jacobs.

Young man, you’ve got a lot of explaining to do. — opening intertitle of Star Spangled to Death

Ken Jacobs’s 1969 Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son — a 115-minute visual analysis of a 1905 short film with the same title, probably directed by D.W. Griffith cameraman Billy Bitzer — introduced me to the modernist appreciation of so-called primitive cinema, teaching me with its seven swarming tableau-like shots that these films were rich and complex and in no way deserving of the term “primitive.” When I saw his 1978 short The Doctor’s Dream, which intricately re-edits a trite educational narrative with sound, it too knocked my socks off. The only other Jacobs works I’ve seen are a couple of “film-performance” pieces that use early documentaries projected in 3-D, and Little Stabs at Happiness (1960) and Blonde Cobra (1963), shorts devoted to the cavortings of performer and future filmmaker Jack Smith and a few of his cohorts in run-down Manhattan locations. I like these two pieces less than Smith’s own films, Scotch Tape (1962) and Flaming Creatures (1963). Scotch Tape is derived from one of the shooting sessions for Jacobs’s magnum opus, Star Spangled to Death, and Jacobs’s beautiful compositions and the way they incorporate surrounding debris probably influenced Smith.

Jacobs’s oeuvre is much larger than these few films, so I have only a limited sense of his work as a processor and juggler of other people’s material and as a generator of his own. Now 70, he has been an influential teacher of critics, programmers, and other filmmakers — including Steve Anker, Alan Berliner, Dan Eisenberg, Amy Halpern, Richard Herskowitz, Jim Hoberman, Ken Ross, Renee Shafransky, and Phil Solomon (to cite the list compiled by critic Scott MacDonald).

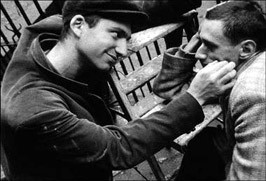

Jacobs was the focus of a retrospective at the Rotterdam film festival last month, but I couldn’t find time to attend, and I knew I had a tape waiting for me at home of the work I was most interested in seeing — his six-and-a-half-hour video “completion” of Star Spangled to Death, most of which was collected or shot between 1957 and ’59 and has been shown in various shorter versions on film ever since. It’s showing in two parts this Saturday and Sunday and next at Chicago Filmmakers, each part slated to run about three and a half hours, including an intermission. “The original was meant to test human tolerance,” Jacobs once said, referring to one or more of the early versions. Yet the materials on view are neither physically nor conceptually hard to watch, nor are they uncharacteristic of Jacobs’s work. Apart from some pointed intertitles, they consist mainly of scenes of Jack Smith and his friend Jerry Sims maniacally clowning around in various low-rent costumes and long portions of hokey artifacts — a racist, pseudoethnographic documentary about the kindness of an enlightened American couple toward quaint African savages, racist extracts from Hollywood cartoons and musicals, a documentary about conditioning monkeys using artificial mothers, Richard Nixon’s infamous Checkers speech, and a film promoting Nelson Rockefeller’s reelection as governor of New York.

What do these ingredients add up to? A history lesson of sorts and a satire on white American entitlement, something that’s also encapsulated in the title. In the program notes Jacobs describes the film as “an antic collage combining found-films with my own more-or-less staged filming (I once said directing Jack and Jerry was like directing the wind). It is a social critique picturing a stolen and dangerously sold out America, allowing examples of popular culture to self-indict. Race and religion and monopolization of wealth and the purposeful dumbing down of citizens and addiction to war become props for clowning. In whimsy we trusted….[Jack Smith’s] character, The Spirit Not of Life But of Living, celebrates Suffering, personified by poor, rattled, fierce Jerry Sims, as an inextricable essence of living.”

I find it puzzling that Jacobs chose to include the documentaries nearly in their entirety, altered only by things such as TV interference, occasional cutaways to other material, or seemingly disconnected voice-overs by Smith and Sims — as if everything these films had to say about his theme and their power “to self-indict” was self-evident. This is a dangerous and potentially solipsistic supposition, though it’s perhaps understandable given that Jacobs was in his mid-20s, poor, angry, alienated, and ambitious. (Smith was older by a year, Sims by roughly a decade.) But what does it mean for us to encounter this material today?

I must also confess that sometimes I’m bewildered by what Jacobs included. It’s easy to understand his disgusted fascination with Al Jolson in blackface arriving on a mule at an all-black Heaven in a slick, lavish production number from the uncredited 1934 Wonder Bar. But is he disgusted with or merely fascinated by a subsequent segment, from Oscar Micheaux’s 1937 black independent feature God’s Step Children (credited), in which the straitlaced black hero says to the black heroine, “The Negro hates to think. He’s a stranger to planning”? Jim Hoberman has written (to my mind somewhat dubiously) about Micheaux as an unconsciously experimental filmmaker, but it’s by no means apparent that Jacobs shares this position. And what about the subsequent section — a 1994 speech by Khalid Muhammad praising Long Island Railroad killer Colin Ferguson for shooting whites and comparing him to Nat Turner, heard in voice-over while Jacobs’s camera follows a beautiful white cat walking next to a fire escape? Clearly multiple ironies are at play here, but what precisely are they?

Reflecting on the multiple forms of racism exposed in Jacobs’s found footage, I was reminded of a recent protest in France about the editing of a DVD release of 63 Tex Avery cartoons made for MGM in the 40s and 50s that cut racist details involving Japanese people and blacks. (Curiously and perhaps significantly, the dumb-Indian caricatures in the 1944 Big Heel-Watha on this four-disc set are left intact.) It seems lamentable that this airbrushing of the historical record may make the originals more enticing to some people, yet I’m not sure I’m more comfortable knowing that Jacobs, simply because he’s an experimental artist, probably could have gotten away with including all of Avery’s 1947 Uncle Tom’s Cabana if he’d wanted to (the French DVD doesn’t include any of it). And I doubt that Jacobs will get away with an anti-Islamic intertitle in Star Spangled to Death, since there’s no evidence of irony and he doesn’t appear to be quoting anyone.

Everything in this video winds up being tiresome at one point or another, which seems part of its design. But complicating this formula are present-day reflections in the form of intertitles, many of them quite moving. They historicize the project, explain how the concept developed, and add the context of George W. Bush and his team (“Forget ‘far-right ideologues.’ They’re crooks”) and the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Some of these intertitles evoke the poetic cadences of similar punctuations in Jonas Mekas’s diary films; others are more prosaic. Appearing over a freeze-frame of Jacobs and Smith is the statement: “We expected Cinder Planet. / We didn’t expect the Sixties. / It was a mixed bag, to be sure / but it shook the owners. / It looked for a while / like the real New Deal.”

One way of justifying the unwieldy length of Star Spangled to Death would be to see it as a way of expressing the congealed no-exit feeling of the late Eisenhower years — the sense of uniformity stretching into infinity, marked by semicomatose complacencies such as the TV shows of Perry Como and Ed Sullivan as well as Your Hit Parade and I’ve Got a Secret. For all their adolescent and even infantile mugging, Smith and Sims are often clearly decrying the way their urban playpens resemble prisons — a point often underscored by Jacobs’s decor and mise en scene — before collapsing into abject despair. “The Future decides this is no place for The Future,” reads one intertitle, which is soon followed by “Another day without a future, but what the hell, another day.”

Within such a morose context, Jacobs looks back nostalgically to the 30s — to the deprivations, the kitsch, the crazed dreams of plenitude — and sees a kind of paradise. And within the same context, the frenzied yet bored dress-up games of Smith and Sims seem like stabs at transcendence. By the 50s, Jacobs writes in the program notes, “Hollywood with some few exceptions had gone numb, frantic and numb in this time of fascist ascendance and cultural impoverishment. The enemy had switched from Right to Left at the end of World War II and the owners had returned with a vengeance. Their message was simple: ‘Shut up and do what you’re told.’ War had done the trick of loosening industry from its Depression fix and war would now be America’s raison d’etre.” One might even say that Jacobs’s inability to finish Star Spangled to Death in its own era — the lab costs were prohibitive — is yet another symptom of the frustration and inertia the work as a whole is describing.

At the heart of this project in its final form is a conceptual complication that Jacobs hasn’t addressed. It’s one thing to be trapped in the late 50s, and quite another to be making a film in a subsequent era about being trapped back then. We’re given a mix of Jacobs in his 20s and an older and wiser Jacobs looking back at his earlier self. The young Jacobs seems relatively unaware of the efforts at resistance that were appearing around him, most notably in the work of beat writers such as Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs. The older Jacobs can see himself as a contemporary of that movement and says so in his program notes.

More generally, context changes everything, a fact illustrated with striking clarity by another bohemian Manhattan-based film that was started in 1957 and later substantially reworked — John Cassavetes’s Shadows. The original print was lost in the early 60s, but Cassavetes specialist Ray Carney recently tracked it down. In 1960 critic Jonas Mekas, writing in the Village Voice, celebrated the first version of the film as a major aesthetic breakthrough but denounced its successor, the version everyone knows, as a commercial sellout. Was he right? The original turned up at the Rotterdam film festival in January, so one might think this question could finally be answered. But the ground under our feet has shifted so much over the past four decades that the answer is neither easy nor simple. Most people in both eras would probably consider the later, reworked version superior. Yet much of what looked new and transgressive back then now looks old and familiar, and parts that no one, including Mekas, paid any attention to — such as the original version of Charles Mingus’s score — now look genuinely fresh and experimental.

Not having seen the earlier versions of Star Spangled to Death, I can’t compare them. But I can say that Jacobs’s current marathon undoubtedly benefits as well as suffers from its lack of definition. The advantage is that by eluding and even confounding all generic categories, it fulfills the traditional aspiration of the antibourgeois avant-garde to shatter certainties. But it also takes on a recognizable shape and purpose once it belatedly manages to define its political focus, and that makes the earlier sections look a bit like waffling. Though I’m touched by Jacobs’s evocation of 50s angst, I’m even more moved by his crystal-clear anger about America today — and by his refusal to succumb to despair.