My “Global Discoveries on DVD” column for the Winter 2015 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

For now the truly shocking thing was the world itself. It was a new world. and he’d just discovered it, just noticed it for the first time.

— Orhan Pamuk, The Black Book

I: Some Conspicuous Absences

As a rule, this column has been preoccupied with what’s available in digital formats, but I’d like to start off this particular quarterly installment with a list of some of the things that aren’t available, at least not yet. This alphabetical checklist is by no means even remotely exhaustive and is entirely personal, based on a few of my recent experiences:

Alain Resnais (two titles): The two most glaring lacunae here are Resnais’ first major film and the last of his features, neither of which can be found yet with English subtitles. Les Statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die, 1953), written by Chris Marker, a remarkable half-hour essay film about African sculpture, also qualifies as his own first major film work –- its beautiful and corrosive text is the first one Marker chose to print in his (still untranslated) two-volume 1967 collection Commentaires. It appears that the film’s unavailability on DVD or Blu-Ray in subtitled form can be attributed to two forms of censorship -– French political censorship when the film first appeared (which lasted for several decades), and North American capitalist censorship (which is apparently still in force). As for Aimer, Boire et Chanter (Life of Riley, 2014) -– which I regard as a sweet postscript to Resnais’ career, but not a major effort like his preceding Vous n’avez encore rien vu (You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet, 2012) — I suspect this is only a matter of time. But if you’re as impatient to see the film as I was, you can forgo the need for subtitles by ordering Life of Riley from Amazon (in Alan Ayckbourn: Plays 5) and Aimer, Boire et Chanter on DVD without subtitles from French Amazon. [2016: This is now available in the U.S. with English subtitles.]

I’m now inclined to view most of Resnais’ career as a whole as a kind of evolution or mutation from “high” literary modernism (as represented by Cayrol, Duras, Marker, Queneau, and Robbe-Grillet) to “lower” boulevard theater and its pop-literary (or “vulgar modernism”) equivalents (as represented by Aykbourne, Bacri and Jaoui, Barde, Bernstein, Feiffer, Gailly, Laborit, Semprun, and Sternberg). I’m not sure where to place Anouilh, Forlani, Gruault, and Mercer in this too-neat configuration, and my placements of Semprun and Sternberg (among others) might also be contested, but it seems clear, in any case, that it was the latter tendency in Resnais’ changing taste that ultimately triumphed over the former.

The Asthenic Syndrome. In my second World Cinema Workshop, given at Béla Tarr’s Film.Factory in Sarajevo last September — my third teaching stint there — one of the most popular things I screened was Kira Miratova’s highly transgressive and visionary post-glasnost masterpiece (1989), which hasn’t dated at all, but I had to depend on a borrowed pirated copy in order to screen it at all with subtitles.

Erich von Stroheim (several titles). Asked by a Czech director in Bologna last June how I might persuade a young person to see a silent film, I replied, “By saying that Stroheim knows more about people than Spielberg does — and more than we do.” So it’s astonishing to me that one of the very greatest of all silent directors is so inadequately represented on DVD and Blu-Ray, unlike (say) Dreyer and Murnau — especially in North America, where the only available titles are Blind Husbands (on DVD from Kino Lorber), Foolish Wives (on Blu-Ray and DVD from Kino Lorber), The Merry Widow (on DVD from the Warner Brothers Archive Collection), and Queen Kelly (on DVD, again from Kino Lorber). Admittedly, this comprises four solid features, but it still leaves out Greed (the most important and, for me, along with Foolish Wives, the best) and The Wedding March (for many others, Stroheim’s greatest), not to mention two partially directed Stroheim features, Merry-Go-Round and Hello, Sister!

Greed is commercially available in France and Spain, albeit in less than ideal copies, whereas The Wedding March, to the best of my knowledge, isn’t available anywhere. I wonder if the reasons aren’t at least partially ideological, combined with the fact that some critics seem to pretend to know about Stroheim’s work without having actually seen it. I’ll never forget an evening in 1965, when I was an undergraduate at Bard College; John Simon turned up for a lecture and proceeded to read his forthcoming putdown of the third New York Film Festival, which, for him, offered not a single “first-rate” or “outstanding” film — although it had included Alphaville, Le Petit Soldat, Les Vampires, Gertrud, Not Reconciled, Walkover, and much else that is still valued today, including The Wedding March -– nothing, in short, that even hinted of true greatness, such as Sundays and Cybele (see below), a Simon pick of a couple of years earlier. And The Wedding March, by contrast, was “the first part of one of those mammoth Erich von Stroheim films, reveling in lavish but indiscriminate reaction of [sic] physical details, in Stroheim’s impudent display of himself as a supposedly irresistible seducer, and in an intellectual content straight out of the novelistic kitsch of Central Europe.” (For the concluding two sentences, you can go to Simon’s well-named 1967 collection, Private Screenings.) “One of those”? I raised my hand after Simon’s lecture/reading, asking if he had the same opinion about Greed or any of the other Stroheim features, and he sheepishly admitted he hadn’t seen any of the others. I presume he wouldn’t have had any good reason to hunt them down since then, either. So today must be a happy period for him, digitally speaking: Sundays and Cybele is finally available, as is Alfie (another 60s Simon favourite), and Greed and The Wedding March still aren’t. Long live high culture!

Hou Hsiao-hsien (several titles). A good many of his films, too, remain unavailable in acceptable formats; even The Puppet Master (1993), which I regard as his greatest work to date, can be found subtitled only in a pan-and-scan copy, and the no less important City of Sadness (1989) can’t be found at all — except, apparently, from this Canadian source: http://www.learmedia.ca/product_info.php/products_id/1049. (The unavailability of films by the late Edward Yang, I should add, is perhaps even more flagrant.) When it came to Hou’s lesser-known but seminal half-hour segment in the episodic feature The Sandwich Man — which I screened in my second World Cinema Workshop in Sarajevo, and subsequently introduced at a Hou retrospective held at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria — I had to order the original with Mandarin subtitles from yesasia.com, download the English subtitles for free from the Internet, and burn my own copy. (The remaining two episodes in this portmanteau feature are also well worth seeing, by the way, especially the latter.)

Laughter. Only a couple of weeks before I showed The Asthenic Syndrome in Sarajevo, I began my course and weekly film series “The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S.” at the Gene Siskel Film Series in Chicago with Harry D’Abaddie D’Arrast’s exquisitely bittersweet 1930 classic, which I was fortunately able to screen in 35-millimeter –- the closest cinematic equivalent that I know to the best of F. Scott Fitzgerald (though scripted by d’Arrast, Douglas Z. Doty, Herman J. Mankiewicz, and Donald Ogden Stewart). But you can’t even find the full feature on YouTube, which provides only snippets from a lousy dupe.

One Man’s War and Ordinary Fascism. This was a double feature that I screened in my recent World Cinema Workshop in Sarajevo -– two difficult-to-classify essay films (of a sort) using found footage, both about the Nazi era -– and neither one can be found commercially with English subtitles. The first of these (1982), Edgardo Cozarinsky’s greatest film to date, was produced by and for French television, which may provide a partial explanation for its unavailability. But the second, directed by Mikhail Romm in Russia in 1965, is a staple for many of those who grew up in Eastern Europe -– Béla Tarr recalls having seen it in school as a child -– yet if you order it on Amazon, as I did, under the ridiculous title Trumps Over Violence, you’ll wind up with a copy subtitled only in Mandarin.

Peter von Bagh (all titles). It’s a bitter irony that my main mentor in all things digital — the recently deceased and irreplaceable artistic director of both the Midnight Sun Film Festival in Lapland and Il Cinema Retrovato in Bologna, who first convinced me to purchase my first multiregional VCR in southern California in the early 1980s in order to swap items with him -– was also an important filmmaker who always favored celluloid over everything else. People who want to explore his filmmaking should probably start with Helsinki, Forever (2008) if and when it becomes easily available with English subtitles. (Facets Video has shown some interest, but as of this writing nothing final has been set.)

Spring in a Small Town. I’m speaking here of Fei Mu’s remarkable 1948 original -– by common consent, at least within the Chinese-speaking world, the greatest of all Chinese films — not Tian Zhuangzhuang’s interesting if questionable 2002 remake, Springtime in a Small Town. The original is commercially available with English subtitles, but in such a lousy copy that I’m reluctant to guide you to it. The better copy that I screened last fall for my Film.Factory MA students was acquired from a Chinese film scholar who uses it in classes herself, and I hope some enterprising distributor can find some way of making it more widely accessible. [2016: This is now available from the BFI.]

Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) and Orderly or Disorderly (1981). My two favourite shorts by Abbas Kiarostami haven’t yet appeared with English subtitles on commercial DVDs -– mainly, it would appear, because Kiarostami himself doesn’t like them. (As he once put it to me about the latter and better of these, it was made before he regarded himself as a “serious” (i.e., artistic) filmmaker.) On two separate occasions, I tried to persuade my contacts at Criterion and the Cohen Media Group to include either or both of these Kanun shorts as extras on their editions of Close-up or The Wind Will Carry Us, but apparently either the price was too costly or Kiarostami was unwilling.

II: Items Likely (or at least Possibly) to be Overlooked

Aguirre Wrath of God (BFI, Blu-Ray). The last time I looked, two of my favourite Werner Herzog films, Aguirre (1972) and Fata Morgana (1971), were both available in North America, but on separate discs and at exorbitant prices. This edition from the U.K. includes both films (and both in English as well as German versions, with optional Herzog audio commentaries), along with three Herzog shorts from the 60s. When I caught the premiere of Aguirre at Cannes in ’73, in the Directors’ Fortnight, I got off to a bad start with it because of the lousy English dubbing (I vaguely recall some Brooklyn or Bronx accents) and Herzog’s fearless admission in the q and a that the surviving monk’s diary allegedly used as the story’s basis was his own invention. Since then, I’ve become accustomed to Herzog’s wily way with facts, and it’s my impression, after spot-checking, that the original English-dubbed version has been improved or replaced.

All That Heaven Allows (Criterion, dual format). Given Douglas Sirk’s high stock these days, you aren’t likely to overlook this 1955 feature of his, one of his most celebrated. But there’s an off-chance that you might bypass Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992), Mark Rappaport’s major essay film about the male star, which is one of this release’s plentiful extras (along with some fascinating interview material with Sirk), and you shouldn’t.

Battle in Heaven (Carlos Reygadas, 2005, Palisades Tartan DVD). My belated catching up with Reygadas’s second feature — enhanced by an interview with him and his lead actress, Anapola Mushkadiz, included as an extra — confirms his interest in doing things that haven’t been done in cinema before and doing them in a way that sustains their own internal logic, without professional actors. In this case, it involves an improbable if not impossible tale about a portly middle-aged chauffeur to a Mexican general (Marcos Hernández), his 20-something daughter (Mushkadiz), who secretly works at a ritzy bordello (like Deneuve in Belle de jour), the chauffeur’s portly family and their botched kidnapping that results in the offscreen death of a kidnapped infant, and lots of religion. The fact that it all may seem implausible or even unbelievable is why some people dismiss it, but the fact that Reygadas puts it all on-screen and holds my interest is good enough for me. Although I can’t quite figure out everything that happens here, even with the assistance of the helpful interview, Reygadas’s respect for all his characters kept the proceedings afloat and meanwhile kept me entranced. Béla Tarr once suggested to me that this may be Reygadas’s best picture, and I wonder now if the beautifully choreographed camera movements have something to do with his preference.

Big History (Lionsgate, DVD). But probably the biggest revelation for me of the past quarter (aside from Locke: see below) is the 17-episode, over seven-hours-long 2013 TV series Big History (with an additional half-hour or so of bonus footage), available from U.S. Amazon for $19.98 and compulsively watchable -– I went through the whole package in only a day or so. My curiosity was instigated by an article by Andrew Ross Sorkin in the New York Times Magazine about billionaire Bill Gates discovering this package — a college course taught by Australian professor David Christian — while working out in his private gym, and then deciding to use this TV series as the basis for a project to try to revolutionize the teaching of history in both American high schools and colleges. Combined with my subsequent encounters with Chuck Workman’s Magician (a new documentary about Orson Welles in which I play a minor part) and Laura Poitras’s Citizenfour, this suggests that it’s possible to use documentary material to make a movie rather than a film –- an undertaking that becomes especially evident in the spy-thriller mechanics of the latter, which contrives to turn Ed Snowden and Glenn Greenwald into full-fledged movie stars, but is also plainly visible in the razzmatazz graphics and punchy, TV-commercial-style presentation of Big History, which manage to teach, proselytize, and entertain all at the same time.

A list of the 17 episodes’ titles will give you some idea of the breadth of material involved: “The Superpower of Salt,” “Horse Power Revolution,’” “Gold Fever,” “Below Zero,” Megastructures,” “Defeating Gravity,” “World of Weapons,” “Brain Boost,” “Mountain Machines,” “Pocket Time Machine,” “Deadly Meteors,” “Decoded,” “Rise of the Carnivores,” “The Sun,” “Silver Supernova,” “H2O,” and “The Big History of Everything” (a roughly chronological recap of the preceding episodes). And for an ideal bonus feature, you should order separately Cynthia Stokes Brown’s book of the same title, subtitled From the Big Bang to the Present.

Borgen (MHZ Networks, DVD). When I recommended Big History to James Naremore, he countered by recommending to me another recent TV series, a Danish political drama, and I ordered the first season (ten hour-long episodes, with two writers and four directors). By now, I’ve watched the whole package: the intelligence and energy of the first episode in crosscutting between two interlocking scandals (one potential and the one actual enough to help swing an election) got me hooked for the remaining installments, not to mention several more scandals.

Unlike Big History, there’s little here that strikes me as “new” in terms of filmmaking or content, (apart from some mordant flashbacks and flash-forwards to chart the history of a romantic relationship), but as a canny drama about how politics works, it’s utterly absorbing –- and arguably even better than Gore Vidal’s The Best Man. I’ve already ordered the show’s two remaining seasons, eager to discover what happens to the series’ two over-achieving heroines (a prime minister and TV journalist) and the troubled but efficient spin doctor who shuttles uneasily between them.

Confessions of an Opium Eater (Warner Brothers Archive Collection, DVD). Along with Union Depot (see below), this is one of the hidden treasures recently made available in the Warner Archive Collection; it’s also known as Souls for Sale and Evils of Chinatown. Allow me to quote from my Chicago Reader capsule: “Despite the title, this film has virtually nothing to do with Thomas De Quincey’s book. But it happens to be one of the most bizarre, beautiful, and poetic Z-films ever made, and probably the only directorial effort of Albert Zugsmith that is almost good enough to be placed alongside his best films as a producer (e.g., Touch of Evil, The Tarnished Angels, Written on the Wind). Vincent Price stars as the black-clad 19th-century adventurer, involved in a San Francisco tong war and with runaway oriental slave girls; Linda Ho, Richard Loo, and June Kim also figure in the cast, and Robert Hill is responsible for the singularly pulpy script. A claustrophobic fever dream with strange slow-motion interludes and memorable characters, this is the kind of film that you remember afterward like a hallucination …(1962).” (Zugsmith, by the way, produced as well as directed Confessions; for a more typical example of his instincts as a producer of exploitation pictures, check out Jack Arnold’s politically duplicitous but entertaining 1958 High School Confidential, recently out on an Olive Blu-Ray.)

Eraserhead (Criterion, Blu-Ray). As with All That Heaven Allows, you aren’t likely to overlook this deluxe edition, which includes a 4K digital restoration of my favourite Lynch feature and countless extras, including six Lynch shorts, a 2001 documentary of his about the making of Eraserhead, his own video introductions to everything, and a great deal more. What you might overlook is that he steadfastly refuses even today, 37 years after the film’s release, to reveal how he created the baby in this first feature –- something which, I must confess, I find even more disturbing and terrifying than anything in Eraserhead per se.

I’ll Always Love You (Olive, Blu-Ray). My first encounter with Frank Borzage’s 1946 classical-music weepie, in delirious Technicolor, which manages to oscillate between the sublime and the ridiculous just about every time you have to catch your breath, offers a kind of conundrum to critics uncertain about how seriously they should take it. Kent Jones in his important essay on Borzage in the September-October 1997 Film Comment tries to navigate the problem in one breathless sentence: “I’ve Always Loved You is a misleading title for an extreme film brought to the brink of madness by its candy-box color scheme and completely disconnected acting, in which various forms of soaring communion (master/disciple, music/ musician, callow lovers out of balance) are mingled and hopelessly confused, then sorted out through the medium of an unsuspecting third party.” (For the record, the film’s working title was Concerto.) Almost a quarter of a century earlier, in the Spring 1973 issue of Focus!, John Belton tried for a mainly straight appreciation (included in his 1983 collection Cinema Stylists). But by far the most comprehensive, detailed, and helpful critical treatment that I’ve encountered, which also responds to Belton’s piece, is in Hervé Dumont’s invaluable 1993 book on Borzage, published in English translation by McFarland in 2006. For me, the beauty of the film largely resides in how completely Borzage can make an extended performance of Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Piano Concerto indistinguishable from the film’s dramatic action –- a rare and stunning achievement.

John Cassavetes (Too Late Blues in a Masters of Cinema dual format set, Love Streams in a Criterion dual-format set). I might have made earlier trips to Brooklyn from Manhattan, but the earliest one I can remember was to a large Loews theater there to catch the first New York engagement of Cassavetes’ second feature in 1961. Like virtually everyone else who had seen Shadows (many times, in my case), I found it disappointing, yet hardly deserving of the utter scorn it received from most serious reviewers at the time (apart from Parker Tyler in Film Culture), who seemed committed to the notion of “film” over “movie” even when they didn’t clearly understand what the differences consisted of, especially for the filmmakers involved. After all, even Shadows had its phony and contrived moments, which critics were willing to overlook, and not even Dwight Macdonald seemed to grasp that the film was about the selling-out that Cassavetes signing a contract with Paramount entailed. Even so, Everett Chambers’ singular performance in a stereotypical role as an evil agent is every bit as remarkable in a way as Rupert Crosse in a non-stereotypical role (and Ben Carruthers in a no less stereotypical role) in Shadows, and I would still defend some of the tactical “errors” in Too Late Blues as vibrant indicators of Cassavetes’ authenticity. As I wrote for Soho News in 1980, “For many critics, the height of absurdity in Too Late Blues is reached when Bobby Darin forces Stella Stevens’ face into a sink after [her character’s suicide attempt], and there is a sudden cut to her face under the faucet as seen from the vantage point of the sink drain. Cassavetes’ refusal to tear away from an actress’s face at a crucial moment, regardless of all the technical gaucheries and jeers that this will cost him, is largely what his awful, irritating integrity is all about.” In his mainly sympathetic video interview about the film — one of many extras in the Masters of Cinema package — David Cairns persists in denigrating this arty shot, but for me the film would be diminished without it, just as the outrageous cuts to the actor replacing the dog in the closing scene of Love Streams, which are even harder to justify “logically,” are both ridiculous and irreplaceable.

Much is rightly made in the extras on Too Late Blues of the relevance of jazz to Cassavetes’ art, even after acknowledging that the dialogue in his films was mostly scripted, and it’s important to bear in mind Miles Davis’s insistence that an essential part of the art of jazz is the capacity to make mistakes –- a truism about risk-taking and passionate creativity that makes the pile-driver mechanics of Whiplash seem even more like egregious nonsense (even if they’re apt to elicit hosannas from some of the unlikeliest quarters). Love Streams — in some ways my favourite of all of Cassavetes’ films, complemented by Criterion with copious extras –- is full of such “mistakes,” none of which I would be happy to do without.

Keeper of the Flame (Warners DVD). I hasten to add that without the jazz context, mistakes are most often simply mistakes, and I must say that I regard this 1942 MGM George Cukor/Spencer Tracy/Katherine Hepburn opus as a whopper. I was driven to watch it by Donald Ogden Stewart (see Laughter, above) having described it as “the picture I’m proudest of having been connected with -– in terms of saying the most about Fascism that it is possible to say in Hollywood.” Whether or not Louis B. Mayer actually walked out of the Radio City Music Hall opening in a huff, as Stewart liked to think he did in his 1975 autobiography By a Stroke of Luck!, the sheer silliness of the story is, alas, what endures.

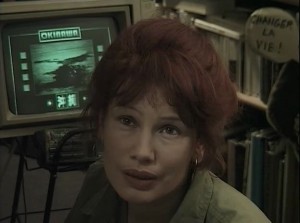

Level Five (Icarus Films, DVD). A good friend who ‘s both a critic and a teacher recently said to me that he thought Chris Marker was a great writer but not necessarily a great filmmaker when it came to composing and juxtaposing images. Insofar as I usually place the start of Marker’s film career at his commentary for Statues Also Die (see above), I could see what he meant. But two weekends later, looking at the opening sequence of Marker’s late masterpiece Level Five (1996), I couldn’t help but wonder if my friend had seen this visually rich (and beautifully written) fictional essay –- something I felt especially primed for through the lucky accident of reading Maureen Freely’s exceptionally fluent retranslation of Orhan Pamuk’s The Black Book at the same time, whose alternate chapters are fictional essays that are every bit as visual (or at least as “visual”) as the purely fictional-narrative stretches.

It pains me now to think how I must have already seen Level Five for the first time a year or two before I met Marker (the only time I did) at the Midnight Sun Film Festival in Lapland in 1998, at which time I’m sure I’d only scratched the surface of this noble sequel (of sorts) to both La jetée (1962) and Sans soleil (1983), another poetic testament about attempting to process (by remembering and forgetting) the 20th century. The fact that Level Five was made when the century was almost over, and when cyberspace was already making its claim on this project, must have made the mission even more urgent. But like Sans Soleil, this is a film that keeps getting more contemporary every time I watch it, and in some ways it’s even more personal (for one thing, Marker’s hands and voice are often present).

The fact that Level Five channels both Laura (explicitly) and Hiroshima mon amour (implicitly) only begins to describe the breadth of its historical, poetic and ethical agendas, which focus mainly on the cataclysmic deaths on Okinawa in 1945, many of them self-inflicted, and the heroine’s grisly task (taken over from her departed lover) of contriving to make a video game out of that battle. Admittedly, Catherine Belkhodja -– Marker’s muse and the film’s only actor, addressing the camera as if it were a computer monitor for much of the time — is no Emmanuelle Riva, especially when she has to address a toy parrot, but it’s characteristic that Marker uses the protracted plaintiveness of this scene as a tonal contrast to its shocking successor, a devastating clip from John Huston’s Let Their Be Light about a traumatized American soldier recovering his memory of Okinawa. I’m still only beginning to explore the reaches of this profound work, but I can already recommend three helpful texts: an essay by Christophe Chazalon included with the DVD, taken from Chazalon’s own web site, www.chrismarker.ch; an essay by Raymond Bellour at www.screeningthepast.com/2013/12/chris-marker-and-level-five/; and a recent book review, www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2014/oct/23/descent-hell.

Locke (Lionsgate, DVD). I saw and liked Steven Knight’s new English feature when it came out, on the big screen, but what amazes me about re-encountering it on DVD, which has led me to value it still more, is how much it’s already been either forgotten or ignored by my colleagues. The challenge of how to classify it may be part of the problem: it’s generally regarded as some sort of tour de force (84 minutes of a guy driving from Birmingham to London, or thereabouts, meanwhile talking to colleagues, family, and acquaintances on the phone), which may be a backhanded and misleading description insofar as it’s not so much a stunt as a story that couldn’t be told any other way. And watching the “making-of” featurette on the DVD and listening to Knight’s commentary clarify that in some ways this is another case of documentary elements rendered in movie terms, even though the story and characters are fictional (and the title hero’s name is a reference to the philosopher John Locke and his definition of the self through a “continuity of consciousness”), because the hero’s drive was shot several times and even the phone calls are real phone calls, recorded live during the various drives and in real time. A road movie? Yes and no –- because in terms of impact and resonance, the movie feels to me more like a heroic, existential western that essentially focuses on the hero’s endurance (a remarkable performance by Tom Hardy) in relation to a series of moral and practical challenges, which inevitably becomes a series of moral and practical challenges for the audience. However one winds up defining it, it’s a definite inclusion on my next annual ten-best list.

The Party (Kino Lorber, Blu-Ray). Although I was once driven by the overestimation of Blake Edwards to call him the Perry Como of American slapstick, it would be silly to deny his talent. And it would be especially silly to deny the virtues of The Party (1968), conceivably his best feature, even after coming across colleagues who still prefer it to Tati’s PlayTime (which it periodically and visibly steals various gags and gadgets from), apparently under the assumption that it’s playing a comparable sort of game with the audience. In fact, as the extras on this disc repeatedly make clear, The Party, made the year after PlayTime, was almost entirely improvised, whereas PlayTime was almost entirely scripted (and required years of preparation). Yet the more important differences remain what they do to and with an audience. Tati isolates audience members from one another by creating a complexity of focal points whereby one spectator will laugh at what another spectator misses -– before drawing everyone together in the film’s closing act and making it a collective experience. In his own way, using very different equipment (i.e., his own voice and body), Richard Pryor does something comparable at the beginning of Richard Pryor Live in Concert, when he engages first with the paranoia of the black members of the audience, then with the paranoia of the white members, ultimately bringing the two groups together once it becomes clear that he’s dealing with a shared paranoia. Edwards, like Tati, is dealing mainly with social discomfort, but he’s basically aiming at everyone in the audience at the same time, guaranteeing that all the laughs come in unison.

Dave Kehr — who likes Edwards a lot more than I do, even though he treasures PlayTime every bit as much — made an interesting observation about The Party on his now-inactive web site four years ago. Disagreeing with Jonathan Letham that the film’s humour goes awry at some point (and with Jean-Pierre Coursodon that it goes awry with the entrance of a baby elephant), he wrote, “I was surprised by that remark in Letham’s book. It’s not that The Party falls apart with the introduction of the elephant, but that it shifts gears thematically and tonally at that moment, from a cold, cruel slapstick with Hrundi [Peter Sellers] as a comic victim to self-consciously Chaplinesque pathos, with Hrundi as the protector of the elephant and the abandoned girl. There always comes a point in Edwards when the slapstick stops being funny and folds back on itself, revealing the pain behind the façade. To me, that’s not a flaw but one of the elements that makes him a great filmmaker.”

Sundays and Cybele (Criterion Blu-Ray). This release offers me my first opportunity to resee Serge Bourguignon’s Oscar-winning first feature since it premiered in New York in 1962, ahead of its French opening, and I’m still not entirely resolved in what I think about the film. The aggressive use of music to hype needlessly an already overwrought closing sequence qualifies for me as an acute case of directorial misjudgment, and some of the fancier camera setups register similarly as overkill, especially unwelcome in a story predicated on a sense of delicacy. Today I’m mainly inclined to regard Bourguignon as a talented landscape artist (partially on the basis of his ignored second feature, a Hollywood effort called The Reward, which struck me as quite interesting when I saw it in Alabama in 1965) with a limited feeling for narrative. But in spite of these misgivings, Hardy Krüger’s and Patricia Gozzi’s performances and Henri Decae cinematography are justly celebrated -– even when the latter seems to trump the former, as Manny Farber complained back in the 60s. In her accompanying essay, “Innocent Love?”, Ginette Vincendeau ably navigates the discrepancies between the willfully innocent readings of most critics in the 60s with the more pedophiliac readings that are more apt to collide with the earlier readings today.

Union Depot (Warner Brothers Archive Collection, DVD). Alfred E. Green (1989- 1960), a studio workhorse with 114 directorial credits listed on IMDB, is a basically unsung figure, yet on the basis of the little I’ve seen, especially of his early 30s work — most notably, Union Depot in 1932 and Baby Face in 1933 -– he clearly warrants further investigation. The opening shot of Union Station, a lengthy take entering and exploring the title location, is a jaw-dropping piece of artful camera choreography and mise en scène, and the 60-odd minutes that follow, featuring Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and a flock of 30s standbys (including Joan Blondell, Guy Kibee. Alan Hale, and Frank McHugh), is pretty impressive as well.

The Vanishing (both versions). When I briefly reviewed the original version of George Sluizer’s The Vanishing (1988) for the Chicago Reader in early 1991, the film had made such a faint impression on me that I was fairly dismissive: “Thematic echoes from Hitchcock’s Vertigo, The Lady Vanishes, and Rope crop up in this 1988 Dutch thriller, about the disappearance of a young woman from Amsterdam (Johanna Ter Steege) during a holiday in France with her husband (Gene Bervoets). [I should have written “boyfriend.”] Delayed exposition about what happened to her and why succeeds in holding some interest, but by the end you may feel you’ve been taken on an unenlightening ride around the block.” So unenlightening, in fact, that when Criterion recently sent me a Blu-Ray– shortly before Twilight Time sent me another Blu-Ray of the much-reviled American remake (1993), also directed by Sluizer — I felt I could watch both as if for the first time, which was literally true of the remake. And I decided to start with the remake.

I was surprised by how much I liked it, and perhaps even more surprised, after I resaw the original, that I still prefer the remake. Both have their virtues — like Stanley Kubrick, I was especially taken with Van Steege’s performance in the first version — but apart from the obvious thematic similarities and directorial echoes, they’re really substantially different films, in terms of structure, characters, and milieu, and not only because of the completely different final act (for which the remake was roundly skewered in the press). Roger Ebert, for one, clearly thought as much when he gave the original three and a half stars and the remake only one, concluding his review of the latter, “I simply know that George Sluizer has directed two films named The Vanishing, and one is a masterpiece and the other is laughable, stupid and crude.”

Both films, to be sure, play elaborate cat-and-mouse games with the spectator throughout that mirror the movements of the plot — specifically, the cat-and-mouse games played by a bourgeois chemistry teacher who gratuitously abducts a young woman at random and her boyfriend, who spends the next several years obsessively trying to discover what happened to her, following diverse clues planted by the teacher. And the fact that the spectator is made to share the boyfriend’s obsessive quest obviously makes Sluizer the allegorical surrogate for the creepy chemistry teacher, cinching the Hitchcockian narrative dynamics that I had already detected in the original. But casting Jeff Bridges, one of my favorite actors, in this part in the remake (a daring move that pays off handsomely) and beginning the film with this creepy character and his preparations for the abduction is one of the two key factors that won me over — the other one being the introduction of a new character (a new second girlfriend for the boyfriend, played by Nancy Travis — to replace the more diffident and strictly generic character in the original) who’s assigned a far more pivotal role in the action.

In her essay for Twilight Time, Julie Kirgo mounts a noble defense for the remake, most of which I can subscribe to, apart from two demurrals: (1) Her claim that “the critical setting for both movies — a roadside service area — is in many ways far more typical, and thus more ominous, in America than it could ever be in Europe,” suggests to me only that she hasn’t spent much time in Europe outside the major cities. (2) Her suggestion that a spunky and industrious working-class heroine “more active than [her boyfriend] and more intelligent than [the villain]” might well have provided an “Americanization-feminist reinterpretation of the film [which] offended…many critics” is for me only part of the probable reason for the remake’s poor commercial and critical reception. An equally plausible explanation is that it was released in the U.S. only a couple of years after the original, when the plot basics were still too fresh in the minds of most reviewers, including Ebert, to enable them to respond to the story as if for the first time.

Conceivably the same problem affected my response to the original when I resaw it. But I would still argue that the rethinking of Suizier that went into the remake, which Ebert and other reviewers interpreted simply as crass commercialism (even though the movie flopped), is no more crass or commercial than Hitchcock ever was in his own deliberations, including when he remade his own classics. In fact, Travis’s character reminded me of Barbara Harris’s role in Family Plot, and the film’s closing gag is every bit as Hitchcockian as many of its earlier passing comic inflections, such as the snapping on of a car safety belt perceived as a potential trap. In any case, I can highly recommend both versions of the film, in whatever order, if you haven’t seen either one; but if you’ve seen only the original, I would urge you to check out the remake as well.

The Walerian Borowcyzk Collection (Arrow Academy, dual format). Unsolicited by me but entirely welcome when it arrives in the mail, this very handsome prize package from my favourite new digital label, based in the U.K. includes Short Films and Animation (including the feature-length animated Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal of 1967), Goto, Isle of Love (1968), Blanche (1971), Immoral Tales (1974), and The Beast (1975), along with an illustrated 344-page book (actually, two books in one –-Camera Obscura, a comprehensive collection of essays about Borowcyzk edited by Daniel Bird and Michael Brooke, and Borowcyzk’s own Anatomy of the Devil, a collection of nine short stories). I must confess that I haven’t kept up with Borowcyzk since his early features, mainly because of vague or misplaced inhibitions about Eastern European surrealism and animation, but my first look at Camera Obscura and my second look at Goto have already brought home to me the errors of my ways.