From the Chicago Reader (December 17, 2004). I’m wondering now (August 2015) whether I underrated Spanglish as much as I overrated As Good As It Gets. But the fact that I keep changing my mind about James L. Brooks probably says as much about me as it says about him. (In March 2016, having just reseen this, I like it still more, although, as always with Brooks, some irritations remain.) — J.R.

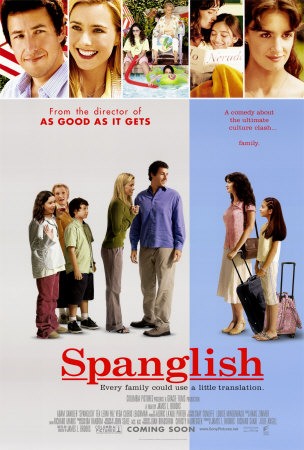

Spanglish

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by James L. Brooks

With Adam Sandler, Tea Leoni, Paz Vega, Cloris Leachman, Shelbie Bruce, Sarah Steele, and Ian Hyland

One reason I can’t regard Pauline Kael as a great film critic is her unshakable belief that she needed to see a movie only once — that she could immediately form an opinion and never have to revise it. She was thought of as an industry gadfly, but her blind faith in first impressions often fit industry calculations perfectly, helping to validate things like test-marketing and seeing movies as disposable.

I readily admit that changing one’s mind about movies days or years later can also be a problem. But we outgrow some films and mature enough to value the challenges of others.

Seven years ago I gave four stars to James L. Brooks’s feature As Good as It Gets, calling it his best film. What was I thinking? Rereading my review made me wonder if I’d been overly invested in the material — or in defending Brooks in general. Whatever my reasons, some colleagues and film buffs were horrified, insisting that the movie was completely phony. Many members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences must have agreed with me, however, because the two leads, Jack Nicholson and Helen Hunt, won Oscars.

I recently saw Spanglish, Brooks’s latest feature, and came away thinking it was gripping despite its plausibility gaps. I knew I had to go back to As Good as It Gets. This time when I watched it I saw an intricate interweaving of truth and falsity that often made it almost impossible to distinguish between the two — the same thing I’d found in Terms of Endearment (1983), Broadcast News (1987), I’ll Do Anything (1994), and Spanglish. I’m now inclined to think that all of Brooks’s films are adept cons — which makes him both fascinating and infuriating.

A veteran producer and writer of TV sitcoms, Brooks is addicted to overkill and oversimplified portraiture. His artistic choices are often compromised, and moral and ideological confusion sometimes surges through his work. As Dave Kehr noted in his Reader review of Terms of Endearment, “Brooks was one of the architects of the [Mary Tyler Moore] sitcom style, and he has television in his soul; his people are incredibly tiny (most are defined by a single stroke of obsessive behavior), and he chokes out his narrative in ten-minute chunks, separated by aching lacunae.”

Yet people who criticize Brooks for test-marketing alternate endings to some of his pictures may have forgotten that movies as prestigious as King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928) and Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941) emerged from the same kind of tinkering — though nothing in the careers of Vidor or Capra rivals Brooks’s insane mutilation of his musical I’ll Do Anything until it had virtually no musical numbers left. Whatever his faults, I have to admit I always learn something from Brooks’s films. Self-destructive neurosis remains one of his thematic standbys, and test-marketing is one of the major subjects of I’ll Do Anything: there are personal implications in his films that make their flaws as expressive and instructive as their virtues.

Spanglish tells the story of Flor (Paz Vega), a young single mother from Mexico who’s hired as a maid by the affluent Clasky family in Bel Air even though she doesn’t speak a word of English. The story is recounted by her 12-year-old, English-speaking daughter Cristina (Shelbie Bruce), who narrates the story five years later in flashback. None of the Spanish dialogue — Flor only belatedly teaches herself English — is subtitled, but Cristina often interprets, sometimes to great comic effect (Vega herself speaks only Spanish and learned her English lines phonetically).

John Clasky (Adam Sandler), a dedicated, easygoing father, runs a chic restaurant where he serves as chef. His wife, Deb (Tea Leoni), a hysterical neurotic, has recently lost her job at a commercial design firm and is undergoing an identity crisis. Her mother (Cloris Leachman), a former jazz singer and quiet alcoholic, also lives in the house and offers her daughter the kind of wise counsel that Helen Hunt’s mother (Shirley Knight) does in As Good as It Gets. The two kids, Bernice (Sarah Steele) and Georgie (Ian Hyland), seem to do a pretty good job of holding their own, but actually we know little about Georgie, though Bernice is both generous and resilient.

The family moves for the summer to a Malibu beach house that’s inaccessible by bus, and Deb persuades Flor to move in. She brings her daughter, and serious conflicts arise between the families once Cristina starts to be seduced by the Claskys’ affluent lifestyle and apparent generosity, particularly Deb’s. Meanwhile, John and Flor’s mutual passion for parenting (another one of Brooks’s thematic standbys) draws them together, and familial and interfamilial crises ensue.

Brooks should get credit for making a bilingual movie without subtitles that people who don’t speak Spanish, like me, can follow, and for focusing on a segment of the American population that’s rarely dealt with directly in the mainstream. It’s not the first time he’s had a character like Flor; in I’ll Do Anything Nick Nolte has a Latina neighbor who’s a mother and sometime babysitter. Brooks should also be praised for taking on another American unmentionable, class difference, which is also central in I’ll Do Anything and As Good as It Gets. He doesn’t show us Flor doing housework, but he does give us a funny if highly implausible scene in which she negotiates her salary with secret coaching from Deb’s mother.

Up to a point, I’d also defend Brooks’s unabashed, old-fashioned notions of good and bad behavior and good guys and bad guys — if only because he does such a persuasive job of showing us the goodness of both John and Flor as parents, even when their cultures and standards conflict. (Sandler’s performance is his richest to date, surpassing his work in Punch-Drunk Love, and Vega, with her adroit body language, never lags behind him.) But I’m less impressed by the way he sets up Deb as an easy target, shaming both himself and us by repeatedly encouraging us to congratulate ourselves for disapproving of her self-absorption and fake liberalism. A recent production story by Nancy Griffin in the New York Times suggests that Deb is Brooks’s partially unconscious self-portrait, but this only underlines how often self-hatred and narcissism vie for supremacy in his characters.

Brooks has an uncanny talent for making us feel insightful. When Deb buys Bernice clothes a size too small as a way to encourage her to lose weight, her thoughtlessness — which gives Flor an opportunity to display her own cleverness — is spelled out by Bernice and John with such eloquence that we think we figured it out all by ourselves.

The line that made me laugh the loudest, delivered by Deb’s mother — “Lately your low self-esteem is just good common sense” — later began to bother me as I reflected on how demagogic it was and how superior it had made me feel. Its sting is only slightly lessened by Deb’s countercharge that her mother’s bad parenting is partly to blame. There’s a similar exchange in As Good as It Gets: Hunt, a sensible waitress, interrupts Nicholson, a maniacal, well-to-do novelist, to say, “Stop it! Why can’t I just have a normal boyfriend who doesn’t go nuts on me?” Her mother chimes in with, “Everybody wants that, dear. It doesn’t exist.” This sounds profound if we don’t bother to think about it and at least slightly meaningful if we do. Sometimes Brooks’s ideas are legitimate, but his way of putting them across is dishonest. Sometimes the ideas are dishonest, but his way of putting them across is legitimate. Sometimes we can’t tell which is which. The bottom line may be that Brooks understands how people, both his characters and audience, tick. How he uses that knowledge is another matter.