I can happily report that some portions of the following — which originally appeared in the December 24, 1993 issue of the Chicago Reader—are out of date, because all the films reported here as unavailable (I Want To Go Home, The Decalogue, The Lovers of Pont-Neuf) have subsequently become available. —J.R.

We all know what political correctness is — though the nuances of the term may vary depending on whether you’re inside or outside academia and whether or not you regard it as exclusively the preserve of the left. (Personally, I consider Rush Limbaugh and Andrea Dworkin both charter members of the club.) Commercial correctness in movie ideology, however, has yet to be defined, even though it currently engulfs both the entertainment industry and the audience.

Political correctness can be defined as the demand by members of an oppressed minority—or at least those like Limbaugh who consider themselves equivalent to members of an oppressed minority—to be treated with respect. Commercial correctness, on the other hand, can be defined as the demand of members of a reigning majority—or at least those who consider themselves equivalent to members of a reigning majority—that minority works and positions be treated without respect. The goal of commercial correctness, in fact, is to ignore, impede, and eliminate these works and positions—to remove them from the face of the planet as efficiently and unobtrusively as possible.

Underlying this goal are three basic assumptions: that only the mercantile value of movies can or should justify their existence; that movie merchants are uniquely qualified to teach us about film (including what the public likes and why) and about the world; and that any movies or ideas that are not commercially correct should be kept from the public and stricken from the historical record.

To illustrate the third assumption, let me cite one commercially correct and one commercially incorrect example.

Correct: The more or less successful suppression of Alain Resnais’ 12th feature, I Want to Go Home (1989), scripted by Jules Feiffer and starring songwriter Adolph Green as an American cartoonist on a visit to France and Gerard Depardieu as a French Flaubert scholar in love with American pop culture. To the best of my knowledge, the only U.S. screening this movie ever had was at the Sarasota Film Festival; calls to the New York office of its producer, Marin Karmitz, about the possibility of showing it even in a nontheatrical venue were not returned.

A monstrously unfunny, singularly nightmarish comedy about the mutual and unrequited love of some Americans for French “high” culture and of some French people for American “low” culture, patterned in various ways on comic strips, the film was a critical and commercial disaster overseas. Since then, the English version has been kept out of everyone’s reach. I recently caught the unsubtitled French version on video, and while the film can’t by any normal standard be called an artistic “success”—as critic Bill Krohn observes, it’s Resnais’ equivalent to Skidoo, the 1969 comedy Otto Preminger made after taking LSD—it’s certainly one of the most fascinating and original films I’ve seen this year. I happen to find Resnais a lot more interesting, conceptually and aesthetically, than Altman, De Palma, and Scorsese (I’d much rather see I Want to Go Home a second time than Carlito’s Way), and I’m far from alone in this bias among older U.S. film buffs—the only ones, in many cases, who’ve been able to see his best work. But as a critic and as someone interested in movies, I’m supposed to ignore the fact that he’s made any movies since Mélo, and even Karmitz clearly goes out of his way to encourage this silence.

Incorrect: Back in the 70s, when I was living in Paris, I was naive enough to propose to the Arts and Leisure section of the New York Times a piece about great recent European movies that weren’t being distributed in the United States. I hadn’t yet caught on to the principle that the Times is interested only in goods available in New York. In the same way, when the Academy Awards presented its tribute to Fellini, the show omitted any mention of his last two features, both still undistributed here: better to keep people in ignorance than let them know what they’re missing. (The same applies to the Times Book Review‘s annual roundups of the year’s best—which are invariably those books it was perspicacious enough to review in the preceding year, no second thoughts allowed.)

The New Yorker‘s Tina Brown recently violated this essential New York policy by hiring a young critic, Anthony Lane, who still lives much of the time in London, without telling him that it’s bad manners to mention undistributed movies. In a recent column he refers to both Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Decalogue and Leos Carax’s Les amants du Pont-Neuf—both major European works still unreleased here, though they’re available in England on video. The impertinent idea that such films exist in the world and therefore belong to film culture could never be found in the work of Pauline Kael or her successor, Terrence Rafferty, whose writings generally reflect the more common New York assumption that if you haven’t heard of it, it can’t be very important or interesting.

Like political correctness, commercial correctness is a fairly recent development. It started around the same time that weekly box-office grosses went from a specialized industry concern–to be found only on the pages of trade papers like Variety–to a staple of mainstream reportage, appearing, like batting averages, in daily newspapers and on TV shows. This is a manufactured interest, to be sure: I doubt that many felt culturally deprived in 1983 if they didn’t know whether Octopussy was outgrossing Superman III or vice versa, just as I doubt that many people today are unduly concerned about the weekly sales figures on various Ford and Chevrolet models. This interest has been manufactured by escalating publicity campaigns, which devise countless commercials on TV disguised as “documentaries” or “news reports,” new methods of bribing journalists with glitzy press junkets, and new magazines devoted to advertising as journalism, like Premiere and Movieline. Then there are the fresh gimmicks, the teen movie panels, the formerly commercial-free cable channels running trailers for new releases, the cultivation of so-called critics who supply quotes for ads without even bothering to see the movie. The general idea is to eliminate any distinction between advertising and commentary remaining in the public mind, and then to focus that mind exclusively on the studios’ most expensive campaigns, banishing everything else to oblivion. To cinch the deal, movie merchants suggest that movies come to our attention as a matter of natural law: Last Action Hero has to be dealt with as a central fact of life because God—not Columbia or Schwarzenegger or director John McTiernan—put it there in front of you.

Given this gangbusters approach, one might think that a watchdog/maintenance program like commercial correctness wouldn’t be necessary. But in fact it’s essential to the whole operation: without constant vigilance, some moviegoer somewhere might actually perceive that there are alternatives to mainstream, media-approved cinema. As in Orwell’s 1984, true success is achieved not when all signs declare “Big Brother Is Watching You” but when all citizens decide that they really and truly love Big Brother and no one else.

The Commercial Correctness Awards of 1993 are bestowed on those individuals and institutions that have done the most to foster Big Brother love through their words or actions, either directly or indirectly. In the true spirit of commercial correctness, I’ve tried to limit this list of half a dozen awards to current and upcoming studio releases, but in the few cases where I’ve failed, at least the individuals and institutions involved are as prominent and unyielding as possible.

Individuals:

1. The first award goes to President Clinton for his contribution to the recent GATT discussions–namely his expressed opinion, no doubt supplied by Jack Valenti, the head of the Motion Picture Association of America, that it’s unfair to the American film industry for the French government to give grants to French filmmakers. It’s unreported whether anyone replied that it’s unfair to the French film industry for the U.S. government to give financial assistance to American producers and studio executives, but it’s plain that France—a stickler when it comes to the outmoded concern for quality over profit, in matters involving food and farms as well as the arts—is on the defensive nowadays. Now that the rest of Europe is all but ready to throw in the towel and devote most of its remaining film resources to churning out imitation Hollywood junk, it’s perverse indeed to argue that filmmakers like Robert Bresson, Jean Renoir, Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, Jacques Rivette, Chantal Akerman, Raul Ruiz, and others who’ve often depended on some form of state assistance have even a fraction as much right to exist as Sylvester Stallone.

I assume that when he made his statement, Clinton either didn’t know or didn’t care that France is the only country in the world where directors are entitled to final cut by law; or maybe he thinks that’s unfair too. They’ve had this privilege since 1957—though I hear from some director friends over there that the growing pressures to compete with Hollywood moviemakers and their big-budget ad campaigns have finally, after 36 years, begun to erode the law’s enforcement. The brutal fact is that a filmmaker having final cut is unlikely to make millionaires richer. Even though there may be a few screens left in France not showing Jurassic Park, scraping together the money to fill a few of them with noncommercial pictures, even with the public’s approval, constitutes a gross injustice to Steven Spielberg’s bank account, and our president is to be commended for pointing this out.

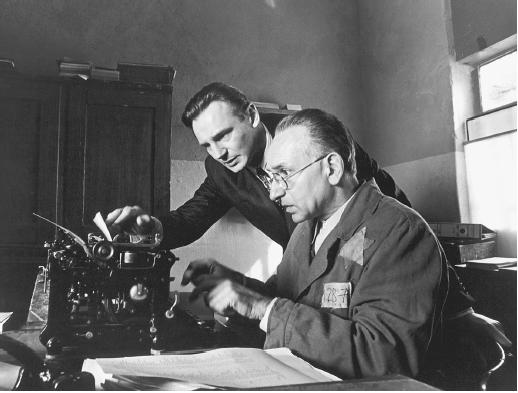

(2) As long as we’re passing out awards to individuals, we might as well include Spielberg, who’s every bit as deserving of a citation as Clinton, and not just because Clinton himself correctly—and commercially— cited Spielberg’s latest picture as something we all should see. (After all, John F. Kennedy crossed a picket line to see and recommend Spartacus, and Schindler’s List is at least as good a movie.) Spielberg’s genius in the realm of commercial correctness rests in convincing both himself and the world that the world is Hollywood and vice versa, and that the world of 50 years ago can best be described by what’s happening today. That’s apparently why he told the New York Times that if Oskar Schindler were alive today he’d be Mike Ovitz, Hollywood’s top agent, and why he told other interviewers that Schindler was just like Steve Ross, the late chairman of Time Warner. If he can’t make up his mind, at least the alternatives he comes up with are close to home and homogeneous. As New City‘s Ray Pride pointed out to me, Schindler’s List is dedicated to the six million Jews killed by the Nazis, but then a subsequent title dedicates the movie to Steve Ross; so actually it’s dedicated to 6,000,001 dead Jews.

(3) The final individual to be awarded is the anonymous publicist who once informed me that the reason his studio doesn’t screen some of its pictures for reviewers is that they’re “dogs.” This is commercial correctness raised to sublimity (his bosses must be tickled pink): his remark succinctly and frankly establishes that, contrary to appearances, it’s the publicist who actually reviews the pictures, deciding what to show and not show reviewers, and the reviewer who does the publicity, by faithfully following the publicist’s critical cues.

Institutions:

(1) Miramax. Now that this country’s most successful distributor of foreign films has been taken over by Disney—can’t you just imagine a Farewell My Concubine pavilion at Disney World?—the prospect of any alternatives to mainstream fare has become even more remote. More than ever it’s all-or-nothing time: either everyone on the block sees the same movie five times, or else no one can even peek at it once. And Miramax, with its massive interference in the creative process—recutting pictures, forcing directors to shoot happier endings, and for all I know revising the scripts and controlling the director’s daily cholesterol intake—has to be championed as the most commercially correct company around.

As I noted last spring, months after The Crying Game was released serious public discussion of the film was turned into an acute ethical issue thanks to Miramax’s massive campaign to get reviewers to conceal the film’s “surprise.” Again, shades of 1984: critics almost had to start worrying about mumbling information about the surprise in their sleep. What if a spouse or lover overheard them? Would their actions be reported to Miramax? For powers of intimidation reaching this far, this singularly aggressive distributor deserves special recognition. If they don’t make more money in 1994 than they did in 1993, we’ll have to hold a special meeting of moviegoers to see where we all went wrong.

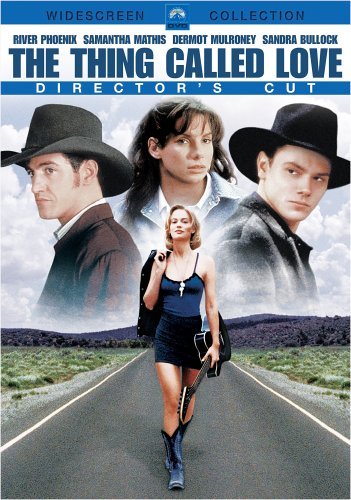

(2) Paramount Pictures. This studio widely advertised and then completely suppressed Peter Bogdanovich’s The Thing Called Love, the best American youth picture I saw all year. A romantic comedy about young wannabe country-western composers and singers in Nashville, it stars Samantha Mathis, the wonderful female lead in Pump Up the Volume, and I’m told that Allan Moyle, the writer-director of that film, had an uncredited hand in the script. You would have thought that the death of Mathis’s costar, River Phoenix, would have made this movie more marketable—that would be the usual cynical, commercially correct thinking—but the word is that Paramount briefly opened the movie in areas with a particular interest in country-western music, found it didn’t do well enough there, and closed the account books on it. (Next stop, video rentals.)

Come again? Test marketing is of course the ne plus ultra of commercial correctness, though in a recent interview Clint Eastwood says that he does without it when he can. And that makes sense, because if you don’t know what you’re doing–the situation of most producers, studio executives, and filmmakers most of the time–previews will probably only make you more confused. To all appearances they confused Paramount, because test marketing The Thing Called Love with C and W fans makes about as much sense as previewing Altman’s Nashville with the same bunch—or testing A Dangerous Woman in a mental hospital. The whole charm of Bogdanovich’s picture is that it takes place in some fanciful world he and the actors have conjured up. That this world bears scant resemblance to the real Nashville is no disgrace, but it wreaks havoc on the film’s commercial possibilities if your basic marketing assumption is that the film must evoke the real world of country-western music. Or maybe Paramount just wanted to kill the movie—it’s fundamental to commercial correctness that the studio’s desires and decisions carry more weight than the filmmaker’s and our own. Ours are supposed to matter only until we plunk down our money, but theirs are meant to last forever and therefore should inspire our awe and gratitude.

(3) MGM. It pretends in its press materials–and therefore has many of us believing–that the plot of Six Degrees of Separation, one of the year’s better movies, sprang full-blown from writer John Guare’s head. In fact, the story actually happened, and more than once. The story behind Abbas Kiarostami’s brilliant 1990 Iranian documentary feature Close-Up is remarkably similar: a show-biz impostor charms his way into a well-to-do household with the promise of flattering screen appearances for his hosts, then gets arrested and philosophically chewed over at length, meanwhile exposing as well as appealing to diverse forms of middle-class voyeurism in us all.

But the point isn’t that Guare was inspired by Kiarostami’s masterpiece; after all, he wrote the play in 1989. More to the point is the fact that the impostor at the center of Six Degrees of Separation is based on a real person, David Hampton, who really conned some well-to-do New Yorkers into believing he was the son of Sidney Poitier—the basic situation in Six Degrees of Separation—and with baroque consequences similar to those in the film. But you won’t learn a word about this from MGM, because (I’m guessing) their lawyers told them to keep their traps shut. Hampton tried to sue Guare for writing about his scam but lost the case. (Would MGM have owned up to the truth if he’d won?)

I suppose it can be argued that what Hampton did is “life” and Guare’s play is “art” and ne’er the twain shall meet—or something along those lines. But the fact remains that the play and movie both raise moral questions—powerfully and beautifully rendered in Stockard Channing’s performance as the wife—about the impostor and what he did being finally reduced to cocktail-party gossip. The same kind of moral questions arise about MGM’s reducing the story to the status of mere fiction. One might maintain that it doesn’t matter, morally speaking, whether this impostor existed or not. But insofar as Six Degrees of Separation purports, with some justification, to be saying something about the modern world and how we process it—how we deal with differences of class, race, and culture, and how media affect our ways of coping—I think it does matter. This is a commercially incorrect assumption, however, and the bottom line, as usual, gets the last word.