From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1999). — J.R.

I recently heard about an American teenager visiting Wales who insisted on calling the Welsh people she met English. When it was pointed out to her that the Welsh didn’t like being identified that way, she said she was sorry but that’s what she’d been taught in school — and it would be too complicated for her to change what she called them.

Given the isolationism of Americans, which seems to grow more pronounced every year, an event like the Chicago International Film Festival has to be cherished. This year it’s offering the city 108 features from 31 countries — 32 from the U.S. and 76 from elsewhere, 49 of them U.S. or North American premieres, as well as five programs of shorts and five tributes. Consider them cultural CARE packages, precious news bulletins, breaths of fresh, or stale, air from diverse corners of the globe — even bad or mediocre foreign movies have important things to teach us. However you look at them, they’re proof that Americans aren’t the only human beings and that the decisions Americans make about how to live their lives aren’t the only options — at least not yet.

Writer-director Kevin Smith (Clerks, Chasing Amy) didn’t have the excuse of being a teenager when he told an interviewer a few years back that he didn’t have to see foreign films — because he saw Jim Jarmusch films and Jarmusch saw foreign films, so the essence of what foreign pictures had to say filtered down to him. Jarmusch was as appalled by Smith’s statement as I was, if only for what it revealed about his landlocked innocence — the kind that assumes the world can be categorized and summarized in simple terms. But his statement isn’t all that different from the many sweeping judgments that pass for cleverness in our culture. “One of the extraordinary advantages of growing up French,” begins David Denby’s review of Catherine Breillat’s Romance in last week’s New Yorker, “is that you can be absurd without ever quite knowing it” — an advantage presumably denied to world-weary Americans such as himself. To find such a statement funny or true, you have to glide past the fact that it’s describing 58 million people. If a French critic made the same assertion about growing up American, I’d wager that most of us would find the remark boorish and stupid. But too many Americans seem to feel not only free but somehow licensed to define the rest of the world, cheerfully and without shame, in terms of their own limitations.

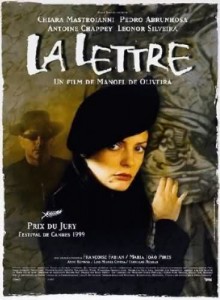

Yet if you look at what’s been happening lately in world cinema–a subject most American critics aren’t much interested in, apart from publicity stunts like the Dogma 95 manifesto — there are signs that the bullying dominance of Hollywood is beginning to encounter some healthy resistance. First there were the controversial prizes given out at Cannes by a jury headed by David Cronenberg to serious and challenging European art movies — Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne’s Rosetta, Bruno Dumont’s Humanity, Alexander Sokurov’s Moloch, and Manoel de Oliveira’s The Letter (the last three are showing at the Chicago festival). Rosetta — the most exciting of the lot and the most visceral filmgoing experience I’ve had all year — gives an unforgettably acute, physical, and unsentimental notion of what it means at the moment to be young and jobless in Belgium; the more mannerist, sprawling, and difficult Humanity is no less informative about working-class life in rural France. The honoring of such vibrant and troubling work — along with a thoughtful day in the life of Hitler and Eva Braun (Moloch) and a contemporary adaptation of La Princesse de Cleves (The Letter) — provoked cries of outrage from the American mainstream press, who were positively livid that the jury had passed over the usual feel-good entertainments from Hollywood. A similar pattern could be discerned in the prizes given by another festival jury in Venice last month and the response to them.

Some signs of resistance are also evident in this country. In Chicago we have the prospect of more art cinemas in the next couple of years and a relocation and expansion of the Film Center. And there’s the recently announced departure of Janet Maslin as the first-string film critic for the New York Times; she’s virtually been a shill for Hollywood in general and most Miramax product in particular, and her interest in world cinema–at least in terms of art rather than business–has been minimal. (As her last Cannes coverage made painfully clear, she’s far more interested in the philistine declarations of Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein than in the artistic strategies of any filmmaker — American or foreign, dead or alive.) Thanks to the influence of the Times, Maslin’s verdicts on foreign movies have played a significant role in deciding which of them get to Chicago, a grotesque state of affairs that’s finally coming to an end; the situation can only get better — unless the Times opts for another industry apologist or a landlocked graduate from the school of Pauline Kael who mistrusts foreigners, such as Denby or Michael Sragow.

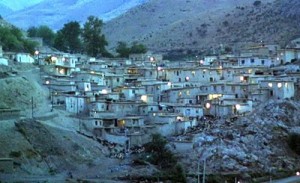

The crippling ideology that insists that movies function as a business first and last leaves no room for those of us who care mainly or exclusively about the art. Consider the response to The Wind Will Carry Us, Abbas Kiarostami’s latest feature, which won the jury prize at Venice and made such a powerful impression on me when I saw it in Toronto that I felt I was walking around inside it for a week. More metaphorical and elliptical and closer to comedy than Kiarostami’s previous feature, Taste of Cherry, it isn’t one of his easiest pictures, and some viewers emerged from it puzzled. (I was among them, but it was a happy and fruitful form of puzzlement.) The film is set in a remote ancient Kurdish village, where a carload of men from Tehran, apparently a documentary film crew, await the death of an ailing woman who’s about a century old, and it further develops Kiarostami’s notion of an interactive cinema where the spectator’s imagination plays a central creative role; at least half of the major characters, including the old woman and most of the crew, remain offscreen. Relatively new to Kiarostami’s work is a focus on nature and a questioning of the morality of the media.

No greater film artist is at work anywhere right now. Kiarostami makes precisely the movies he wants with the modest budgets and crews he requires, and he reaches large numbers of viewers across the globe, who love these movies and consider them important in their lives. But read about this year’s Venice festival in Variety and you discover that it was dull because there wasn’t more wheeling and dealing. Talk to industry commentators about The Wind Will Carry Us — even those who say they revere Kiarostami — and you’ll encounter a lot of sorrowful head shaking because it isn’t his “breakthrough” or “crossover” movie. In other words, they’re not worried about how good or beautiful or important the film is, but whether it will allow some American suits to turn a profit. Poor James Joyce, condemned to be a cultural nonperson by slaving away at Finnegans Wake when he could have signed on as a feature writer for Vanity Fair or even TV Guide and got at least one foot in the door, leading to…what? A Book of the Month Club selection? A sale to DreamWorks? A spot on Larry King? And poor William Faulkner, wasting his time with Light in August when he could have tried for a “crossover” triumph, something along the lines of John Grisham or Stephen King.

This sort of ludicrous reasoning is characteristic of the majority of the current American press — as one can readily see by looking at the movies awarded annual prizes by most critics’ organizations here. But it probably isn’t characteristic of the majority of the American public, who can’t be blamed for missing Kiarostami movies if practically everything in the media and culture insists that Kevin Costner and Kevin Smith movies are thousands of times more important, simply because they’re American. If we have to wait a year or so to see The Wind Will Carry Us in Chicago, that’s our shame, not Kiarostami’s.

It wasn’t hard to find colleagues in Toronto — American, Canadian, Iranian, European — who loved the film as much as I did. Yet we can’t see it at this year’s Chicago Film Festival because Chicago doesn’t have the clout of Toronto. Along with Rosetta, its absence is my biggest regret about this year’s lineup. I can easily think of a dozen more regrettable absences, in descending order of importance: Raul Ruiz’s Time Regained (a daring, magisterial adaptation of Proust), Claire Denis’ Beau travail (a quantum leap for her), Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (not as strong as Dead Man, but imbued with a related sense of tragedy and tradition), Takeshi Kitano’s Kikujiro (which I prefer to both Sonatine and Fireworks because it’s much more mysterious), Zhang Yuan’s Crazy English (an eye-opening documentary from mainland China), Alan Rudolph’s nervy Breakfast of Champions, Ron Mann’s Grass (which proves that entertaining agitprop isn’t necessarily an oxymoron), Bill Forsyth’s Gregory’s Two Girls (a welcome comeback), Erick Zonca’s Le petit voleur (an intriguing follow-up to The Dreamlife of Angels), Samira Gloor-Fadel’s Berlin-Cinema, Steve Gebhardt’s jazz documentary Escalator Over the Hill and Jean-Pierre Limosin’s TV documentary Takeshi Kitano, l’imprevisible. (I’ve omitted all the intriguing contenders I haven’t yet seen, such as Mike Leigh’s Topsy-Turvy, Jane Campion’s Holy Smoke, Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s Sicilia!, and Leos Carax’s Pola X. A few of these films — Topsy-Turvy, Holy Smoke, Rosetta, Ghost Dog, Breakfast of Champions — already have U.S. distributors and are fairly certain to get here eventually; Breakfast of Champions has already opened in New York and Los Angeles.) This is a lot of titles to let slip through your fingers — again the problem appears to be mainly lack of clout. According to Helen Gramates, one of the programmers, the festival made concerted efforts to get The Wind Will Carry Us, Rosetta, and Time Regained, the only three I asked her about.

I’ve seen only a dozen of the titles that the Chicago Film Festival is offering, all of which I can recommend to some extent. (I certainly can’t say that of the nearly 30 films I saw in Toronto, which included some awful stuff, such as George Hickenlooper’s The Big Brass Ring, crudely based on a few elements gleaned from an unrealized Orson Welles script, nearly all of them mutilated beyond recognition.) In roughly descending order of enthusiasm, they are Frederick Wiseman’s Belfast, Maine, Sokurov’s Moloch, Dumont’s Humanity, Aki Kaurismaki’s Juha, John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, de Oliveira’s The Letter, Don Chaffey’s Jason and the Argonauts, Carlos Reichenbach’s Two Streams, Laurent Bouhnik’s 1999 Madeleine, Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart, Gordon Hessler’s The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, and Emilie Deleuze’s New Dawn. Not a bad list, though apart from the Wiseman none of them holds a candle to most of the major omissions I’ve cited.