From the Chicago Reader (September 4, 1992). In the interests of full disclosure, I should note [in April 2018] that I’ve furnished the expanded edition of Transcendental Style in Film with a favorable blurb about Schrader’s new Introduction, and that I regard his latest feature, First Reformed, as the best by far of his films to date (at least among those that I’ve seen), despite some persistent misgivings that are expressed in some of the remarks below. — J.R.

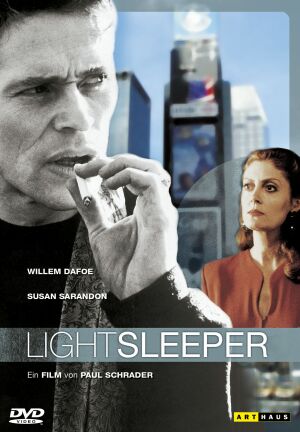

LIGHT SLEEPER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Paul Schrader

With Willem Dafoe, Susan Sarandon, Dana Delany, David Clennon, Mary Beth Hurt, Victor Garber, Jane Adams, Paul Jabara, and Robert Cicchini.

The French New Wave of the 60s offers many examples of film critics of some substance who became filmmakers — among them Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Luc Moullet, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, and François Truffaut. But the commercial American cinema of the 70s offers us only one, Paul Schrader (the only other contender, Peter Bogdanovich, was by his own admission more of a reporter and interviewer than critic before he turned to filmmaking). Yet Schrader has not made a wholly satisfactory transition. As a writer he made his mark on several important features — including Taxi Driver, Obsession, Raging Bull, and (in a minor way, not credited) Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But his career as a director, despite some steady improvement in craft, strikes me as one of the depressing phenomena of the New Hollywood: he’s produced a series of tacky, offensive films that have gained some intellectual and critical respectability only because most critics haven’t been willing to examine them closely. (Light of Day, the only one of his nine features I haven’t seen, is said to be atypical, however.)

What do I dislike so much about Schrader’s oeuvre? Part of the reason for my antipathy is suggested in Robin Wood’s seminal essay of the early 80s, “The Incoherent Text”: “The position implicit in Paul Schrader’s work . . . can be quite simply characterized as quasi-Fascist. This may not be immediately obvious when one considers each film individually, but adding them together (including the screenplays directed by others) makes it clear. There is the put-down of unionization (Blue Collar), the put-down of feminism “in the Name of the Father’ (Old Boyfriends), the denunciations of alternatives to the Family by defining them in terms of degeneracy and pornography (Hardcore), the implicit denigration of gays (American Gigolo . . . ), and, crucial in its sinister relation to all this, the glorification of the dehumanized hero as efficient killing-machine (unambiguous in Rolling Thunder, confused — I believe by Scorsese’s presence as director — in Taxi Driver).”

Other items could easily be added to Wood’s list. For starters, consider the glamorized depictions of racism in Taxi Driver (which critics Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson have analyzed in commendable detail), the misogyny and hatred of sex in Cat People, the overt celebration of fascist ideas in Mishima, and the capriciously ahistorical trashing of radical politics in Patty Hearst. Some of these ideological positions could be debated, of course — the production of Mishima in Japan, for instance, was under constant threat of attack by right-wing Japanese terrorists, and it might be argued that the brand of fascism the film celebrates is not exactly popular. (Unlike American Gigolo, say, Mishima probably can’t be accused of pandering to an audience’s sick biases — its psychosexual sickness is much too personal for that.)

If one ignores Schrader’s (usually unstated) ideological projects and turns to the aesthetic and formal qualities of his movies, the news actually gets worse. His glossy, lurid uses of color seem designed more to grab attention than to do something with it, he employs programmatic wallpaper music (and otherwise unadventurous sound tracks), and except for Patty Hearst, his compositions are usually boring.

One finds elements of vulgar Freudianism creeping into every crevice of Cat People and Mishima, which I regard as Schrader’s most offensive films. One of the characters in the original, 1942 version of Cat People, a highly poetic and antipsychological masterpiece, is a psychiatrist who treats the heroine’s mysterious frigidity. His glib theories and pawing sexual interest in her totally discredit him, so when he’s found torn to pieces, presumably by the angry, feline heroine, the film almost seems to purr its approval. In Schrader’s remake, 40 years later, the psychiatrist has disappeared — there’s no need for him because his leering attitudes have been adopted wholesale by writer-director Schrader. The Freudian explanation has become the film’s official truth about the heroine, suggestive poetry be damned. Similarly, one comes away from the four-part Mishima and its gaudy Las Vegas décor with the impression that the only sustaining value and meaning of Yukio Mishima’s fiction is its vulgar autobiographical subtext, its status as symptom — an assumption identical to that of Hollywood tripe like Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man.

So much for what I dislike about Schrader’s work. I can only add that the genuine intelligence of his criticism in the late 60s and early 70s makes the intellectual cheapness and laziness of his movies seem even more reprehensible.

But one has to admit that the stylistic polish of his work has steadily improved, at least since Patty Hearst (1988); it was sufficiently noticeable in The Comfort of Strangers (1991) to help me overlook the perversity of Harold Pinter’s adaptation of the Ian McEwan novel, at least until the development of the plot made this impossible. Light Sleeper shows some marked improvement even over these two features, both in its performances and in its dreamlike visuals (cinematography by Ed Lachman). But it still seems embarked on a project so wrongheaded and ridiculous that its successes are limited almost by definition.

The problem with Light Sleeper (and with American Gigolo and Taxi Driver) can be summed up in two words: Robert Bresson. I agree with Schrader that Bresson, now retired and pushing 90, is almost certainly the greatest living filmmaker, and I can sympathize up to a point with any effort to emulate him. Beyond this point, however, Schrader’s relentless efforts to make a Bressonian Hollywood feature — a contradictory ambition even at the outset that becomes more and more ludicrous as one examines the details — are a kind of foolishness ultimately more demented than endearing; they demean and diminish Bresson’s work rather than honor it.

One of the major ironies of contemporary moviegoing is that people know imitations and hommages better than originals: there are probably many more people who know the toppling baby carriages in Bananas and The Untouchables than those who know the one in Eisenstein’s Potemkin. By the same token, very few Americans have seen a film by Robert Bresson, but a good many have seen Schrader’s bad imitations, American Gigolo and Taxi Driver. (Because of the intense physicality of Bresson’s films, the solid presence of both sound and image, and their rigorous editing, there are probably no other great films that lose as much on video as his do. Besides, there are so few of them available here on video they might as well come from Mars as France.)

For these people, Light Sleeper looks more like an imitation of Taxi Driver than of Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest or Pickpocket — and in a sense they’re right. One of the first lines in the neo-Bressonian offscreen narration of John LeTour (Willem Dafoe), a 40-year-old delivery boy for an upscale Manhattan drug dealer (Susan Sarandon), is “Labor Day weekend. Some time for a garbage strike” — a detail that has a lot more to do with Taxi Driver‘s vision of encroaching urban filth than it does with Bresson’s sense of the profane, from which it presumably derives.

Among the basic elements of Bresson’s style of filmmaking are three Schrader has never attempted. First, Bresson studiously avoided using professional actors, and carefully trained his nonprofessionals to recite their lines as tonelessly as possible. (The materialist aim is to use people for what they are, not what they and theatrical tradition pretend they are.) Second, he focused on people’s hands and feet at least as often as on their faces and torsos. Third, he minimized the expressive potential of individual shots in order to maximize, through editing, the expressive potential of their combinations and juxtapositions.

What Schrader mainly borrows from Bresson, specifically from Diary of a Country Priest and Pickpocket, are shots of the alienated and tormented hero writing in his diary while reading the entries aloud offscreen, merely alluding to a spiritual crisis by focusing on everyday matters relatively devoid of emotional content. Schrader also makes another stab — the first was in American Gigolo — at reproducing the ending of Pickpocket, when the hero, behind bars, finally discovers his freedom through the love of a good woman. In American Gigolo, the effect is simply laughable; in Light Sleeper, Schrader makes the moment sufficiently independent of its source to render it halfway plausible.

To some extent, Schrader also borrows from Bresson’s own sources — Georges Bernanos’s Diary of a Country Priest and Dostoevski’s Crime and Punishment (the loose inspiration for Pickpocket) — and, superficially, from Bresson’s means of adapting them. But Schrader operates on the naive assumption that the extreme rigor and purity of Bresson’s style can be meaningfully imitated using the usual glitzy Hollywood means: professional actors, slick and jazzy cinematography, high-contrast lighting, and conventional framing and editing — in short, all the formal and technical devices that Bresson took enormous pains to avoid.

Although it’s seldom remarked upon, Bresson’s greatest films are shot through with flashes of mordant wit and humor, not a trace of which can be discovered in Schrader’s work. (Significantly, Bresson’s very first film — rediscovered in France a few years back — is a wonderfully zany and highly physical surrealist featurette of 1934, Les affaires publiques; it suggests a cross between Vigo’s Zéro de conduite and Million Dollar Legs. I went all the way to the San Francisco film festival in 1988 in order to see this rare gem — which still hasn’t shown in either Chicago or New York. When Schrader introduced the screening, he talked about the spiritual quest of Bresson’s heroes as if he were describing one of the later features.)

Schrader’s Calvinist upbringing — the best-advertised and probably most commercial aspect of his background (apart from his fondness for guns) — yields an obsession with various mixtures of the sacred and the profane that passes for “transcendental” in the Entertainment Tonight school of criticism, though it strikes me as an expedient pumping of the audience’s Calvinist desires and guilt feelings, which have nothing to do with Bresson but plenty to do with box office (see Taxi Driver). The same humorlessness that inspired Schrader to write “No artist or style has cornered the transcendental market” in his ponderous 1972 Transcendental Style in Film has also prompted him in Light Sleeper to dream up the New York Post headline “Fall From Grace” to describe the plummeting to her death from “Grace Towers” of Marianne (Dana Delany), LeTour’s former girlfriend, whom he desperately regards for a time as the vehicle of his salvation. If Schrader ever abandoned this transcendental nonsense to explore Bresson’s materialism, he might be on to something serious; but then, of course, he’d have to give up Hollywood forever.

Apart from Lachman’s cinematography, what does Light Sleeper — probably Schrader’s best film to date — have going for it?

A literate script, for one thing. John LeTour may not seem much like a writer, but it must be conceded that Schrader has given the narration and dialogue a certain snap and crackle. Wasn’t it Dizzy Gillespie who noted that he created his style by trying and failing to imitate Roy Eldridge? By the same token, William Faulkner once explained that his prose style grew out of his failure to write lyric poetry. Schrader is no Faulkner and no Gillespie, but in his third silly attempt to appropriate Bresson’s form of story telling and his second misguided effort to remake Pickpocket, he has arrived at a pretty good offscreen narration.

Susan Sarandon, who gets better as an actress every year, is simply breathtaking. I’m not sure what it is that has made her talent blossom so richly, but there is scarcely a gesture or line reading of hers in this movie that comes across as familiar or clichéd, despite the relative thinness of her part as scripted. If Schrader had anything to do with this performance he should be applauded, especially since this shows a talent that has nothing whatsoever to do with Robert Bresson. If he takes this fact to heart, he might eventually learn enough to outgrow father figures altogether.