Written for the Rotterdam International Film Festival in November 2003. — J.R.

In his biography of André Bazin, Dudley Andrew notes in passing that “The Ontology of the Photographic Image” and “The Myth of Total Cinema,” which he calls Bazin’s“first great essays,” were both composed during the French Occupation. I hope I can be forgiven for taking the meaning of the second essay’s title in a direction quite different from what Bazin intended–a direction inspired by the fact that we’re living today under a kind of Cultural Occupation imposed by advertising that currently approaches global dimensions, and which operates under the assumption of another kind of “myth of total cinema”. I’m thinking of the myth that the breadth and diversity of contemporary cinema in its present profusion are somehow knowable and therefore describable, something that can be analyzed in detail as well as evaluated.

Arguably, this was closer to being true during the first half of the 20th century, even though it took nearly all of those 50 years for film history and film criticism to reach the point of finding the very notion of such serious stock-taking desirable. For most of that half-century, taking account of the cinema as a whole was a pretty haphazard affair. By the time it started in earnest with individuals like Henri Langlois and André Bazin, Jean-Luc Godard’s principal mentors, the task of cataloging and evaluating what had already appeared -— which achieves its belated fruition in Godard’s eight-part video series Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1988-1998) —- was the central undertaking. One already feels some of the urgency in such a project in some of the great “catalog” issues of Cahiers du Cinéma containing dozens of filmographies that were put together in the late 50s and afterwards, succeeded across the Atlantic by Andrew Sarris’s monumental “The American Cinema,” first in Film Culture and later in book form —- a project that could then be described, borrowing from the Westerns that were among the most treasured objects of these investigations, as charting an almost virgin territory.

I don’t mean to imply that it was possible for anyone to have an exhaustive knowledge of cinema between 1950 and 1970 —- only that such an ideal was more approachable and imaginable in certain areas. When I interviewed Jonas Mekas for my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver: Arden Press, 1983), he agreed that if someone came to New York or San Francisco during that period with an avant-garde film that he or she wanted to be shown, there were usually one or two places to go. But “beginning with the 70s,” he said, “there were no longer 20 or 30 filmmakers to deal with, but literally thousands making thousands of films.”

More recently, digital video has escalated that figure much further into the stratosphere, and not only for avant-garde films. In the meantime, western knowledge of cinema made in other parts of the world that was mainly or completely undocumented prior to the 80s -— including the cinemas of the Middle East and those of many portions of Asia —- has given the lie to any notion that anyone, even at mid-century, could possibly have known everything that was going on. Today, it’s surely no exaggeration to say that no one at all -— no critic, archivist, distributor, exhibitor, or programmer -— can pretend to know the overall “state” of cinema, which means that all those who continue to hold forth on such matters nowadays are simply lying, most often in a self-serving manner. And as the Argentinian film critic and festival director Quintín has recently suggested to me, film festivals tend to be complicitous with this state of affairs.

As I’ve recently argued in my book Movie Wars (Chicago: A Cappella Books, Chicago Review Press, 2000), such impostures are in fact desirable to those working on behalf of the Cultural Occupiers —- global companies interested only in maximizing the sales of a minimal number of products and which are therefore delighted to hear about the death of cinema as an art form (a cherished mainstream topic in recent years) or as a social or political or intellectual force in the world. This judgment can only clear the way for their relatively limited arsenal of entertainment features and TV shows to be sold even more widely without much fear of distraction.

***

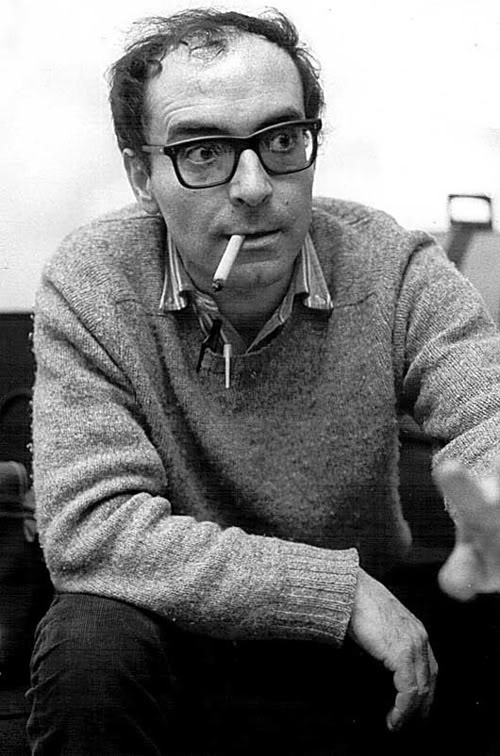

“Whenever you recount a history,” I said to Godard in a 1997 interview (1), “there’s an implication that something is over, and it seems to me that one implication of Histoire(s) du Cinéma is that cinema is over.” “The cinema we knew,” Godard stressed in response. “We also say that of painting.” And the two or three things Godard knew about cinema contained in his monumental video series are predicated on a canon set by himself and his colleagues almost half a century earlier. As the English Godard scholar Michael Witt has aptly noted (2), this ultimately adds up to a myth of cinema in its totality that will expire around the same time Godard does. Yet given the influence of Godard’s viewpoint, it’s the deadliest of ironies that the assumptions underlying his answer to the question, “What is cinema?” should coincide so neatly with the desires of the aforementioned Cultural Occupiers.

Lamentably, Gaumont has cleared rights to the clips (and photographs of other visual artworks) in order to show the video series in France and has ignored the issue of rights regarding the soundtracks and pieces of music used, thus bypassing the opportunity to set an important legal precedent by claiming fair usage of clips in what is essentially, after all, a work of criticism. This accounts in part for the grotesque situation whereby the videos are commercially available only in France — and only in a monaural version that seriously damages the resonance and obscures the methodology of its soundtrack — whereas the stereo version of the soundtrack alone, on CDs, is available everywhere. (Only in Japan, where a box set of eight DVDs has been issued in stereo, is it possible to view the work in its integral form.)

In terms of the video’s overall myth, cinema and the 20th Century are characterized by two key countries (France and the U.S.), two emblematic studio chiefs (Irving Thalberg, Howard Hughes), and two emblematic world leaders (Lenin, Hitler); two decisive falls from cinematic innocence —- the end of silent film that came with the talkies and the end of talkies that came with video —- and two decisive falls from worldly innocence (World War I and World War II). Missing from this highly skewed view of the world is practically all of Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East, and Africa —- not to mention most experimental cinema made everywhere. At least two major Japanese filmmakers, Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu, are given some recognition, and a still from Souleymane Cissé’s Yeelen is seen, but the latter is the only fleeting allusion to African cinema, and the cinemas of Iran, India, and Australia (for instance) can’t be said to exist at all in this scheme. Even worse, adding a certain amount of complacent and (at times) neocolonialist insult are the references to Fritz Lang’s The Indian Tomb, George Cukor’s Bhowani Junction, and Marguerite Duras’s India Song that seemingly “replace” Indian cinema (three great films, to be sure —- but hardly adequate substitutes) and an even more dubious evocation of other “darker” cultures in which Philippe Garrel’s Marie pour mémoire, Jean Gremillon’s Lumière d’été, John Coltrane’s jazz piece “Africa,” White Shadows, Captain Blood, Glauber Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes, and Jean Rouch’s Moi, un noir are invited to rub shoulders with Yeelen.

To be fair, there is evidence that Godard was among the first Europeans who recognized the importance of Abbas Kiarostami, and this recognition took place while he was still working on Histoire(s) du Cinéma. Nevertheless, it’s clear and perhaps also understandable according to his “closed book” policy that he decided Kiarostami played no role in the (hi)story he had to recount. Here is only one clear instance of a collision between history as it’s written and the history that remains to be told, and it points to a much wider weakness and absence in much contemporary film criticism that attempts to generalize about the state of the art, past and present.

***

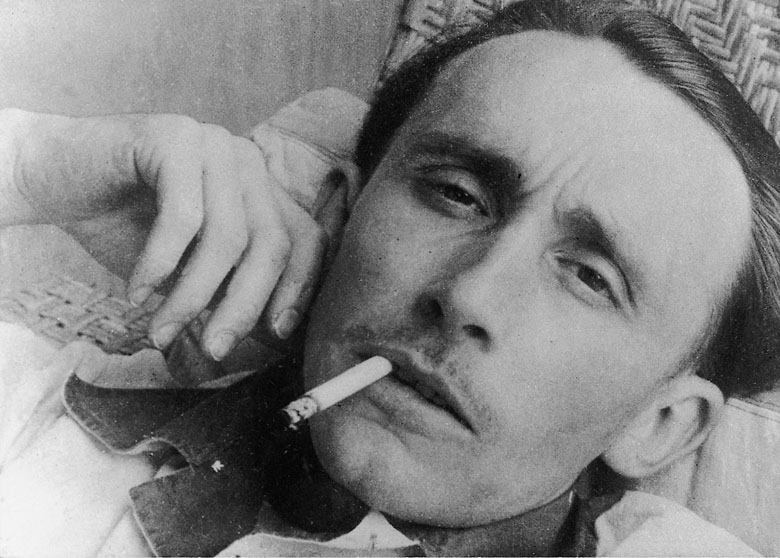

Since the onset of his career, Godard has been interested in two kinds of criticism—- film criticism and social criticism —- and these two interests are apparent in practically everything he does and says as an artist. The first two critical texts that he published (in the second and third issues of Gazette du Cinéma in 1950) are entitled “Joseph Mankiewicz” and “Pour un cinema politique” (“Towards a Political Cinema”), and his first two features, A bout de souffle/Breathless (1959) and Le petit soldat/The Little Soldier (1960), made about a decade later, reflect the same dichotomy.

Histoire(s) du Cinéma, combining these interests, is no different than its predecessors. But even as we acknowledge its multifaceted brilliance as a kind of summation of Godard’s critical enterprise, we also have to recognize, in spite of its advanced form and methodology, that it addresses a “myth of total cinema” belonging to a particular past that is no longer our own -— or, more precisely, a past that becomes our present and future only if we persist in ignoring all the contradictory and ambiguous evidence we have comprising what cinema is in the 21st century. Making sense of the current profusion is no easy matter, but a prerequisite for learning anything about our present situation is acknowledging that our task is to discover what cinema is, not merely to record what it was.

Notes

1.“Bande-annonce pour les Histoire(s) du cinéma de Godard,” Trafic no. 21, 1997, pp. 5-18. Translated as “Trailer for Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma,” Vertigo no. 7, 1997, pp. 13-20. See also “Le vrai coupable: two kinds of criticism in Godard’s work,” Screen 40:3, Autumn 1999, pp. 316-322. (Portions of both articles are recycled in the present essay.)

2.“The death(s) of cinema according to Godard,” Screen 40: 3, Autumn 1999, pp. 331-346.