This review of Frank Capra’s Broadway Bill (1934) first appeared in the August 7, 1992 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

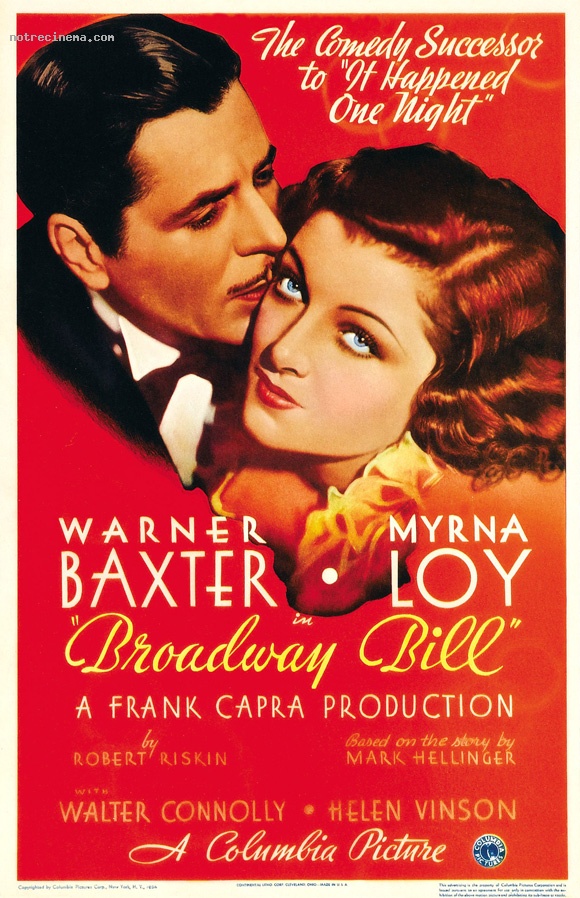

BROADWAY BILL

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Frank Capra

Written by Robert Riskin and Sidney Buchman

With Warner Baxter, Myrna Loy, Helen Vinson, Clarence Muse, Raymond Walburn, Walter Connolly, Margaret Hamilton, and Frankie Darro.

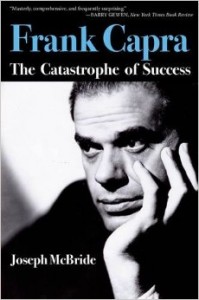

Though it’s surely a coincidence, the theatrical rerelease of Frank Capra’s Broadway Bill and the simultaneous publication of Joseph McBride’s Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success are mutually enhancing in a number of ways.

Capra’s 1934 Christmas release was made for Columbia, bought by Paramount, and withdrawn from circulation over 40 years ago, when Capra was preparing a remake called Riding High (1950) — a Bing Crosby musical with virtually the same plot and dialogue that was so unmemorable that despite numerous TV screenings the film critic for the Boston Globe claimed last month that it had never been made at all. The much feistier Broadway Bill, by contrast, has never turned up on TV, and apart from a few archival airings has remained unseen for over half a century. A breezy if edgy racing comedy laced with some serious ingredients, it isn’t nearly as good as The Bitter Tea of General Yen or It Happened One Night, both of which preceded it, but on the other hand it isn’t as cloying as the worst parts of its successors Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It’s a Wonderful Life.

McBride’s 768-page volume, almost a decade in the making, is quite possibly the most thoroughly researched biography of a film director ever written, as well as one of the most provocative. It’s a major piece of revisionist film history and criticism, invaluable not only for what it has to say specifically about Capra but also for its critique of the American success ethic. A pitiless, relentless work of debunking, it exposes not only Capra, as a liar and partial fraud, but substantial portions of the American public and intelligentsia for buying and supporting — even encouraging — his self-serving cover story.

I’ve never been one of Capra’s champions, though I admire the exquisite textures and feelings of his highly uncharacteristic and still neglected The Bitter Tea of General Yen. Like McBride, I agree with critic Elliott Stein that Capra’s most durable work comes in the 20s and 30s, before rather than after Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936). By this reckoning Broadway Bill comes at the tail end of his most fertile period, characterized by his liveliest and most sensual work with actors, before the populist euphoria in his work took over (although there are foreshadowings of this euphoria in Broadway Bill‘s closing minutes).

Behind the populist filmmaker is a populist myth of a poor Sicilian immigrant who achieved the American dream and never forgot or repudiated his humble origins — a proletarian success story propounded at much length in Capra’s best-selling autobiography, The Name Above the Title (1971). McBride’s often painful contribution is to demonstrate the falsity of this myth, fact by fact and assumption by assumption, showing us not only how it was manufactured largely out of whole cloth by Capra but also how it was collectively willed into being by his audience and critics. (At a climactic juncture in McBride’s narrative, John Ford helps to forge the myth by encouraging Capra to invent an appropriate lie for the conclusion of his autobiography — in effect helping him to “print the legend,” as it’s put in Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.)

The complex portrait of Capra that emerges from McBride’s study is of a narrow-minded, bigoted, and tormented Republican whose obsessive drive for success permanently crippled him. We discover in detail how Capra repeatedly minimized the creative contributions of his major collaborators (such as cinematographer Joseph Walker and writers Robert Riskin and Sidney Buchman) in order to build his own reputation, then crash-landed into success: manic-depressive mood swings left him miserable even after he’d become famous and powerful. (McBride’s subtitle, “The Catastrophe of Success,” comes from Tennessee Williams’s description of his own experience with The Glass Menagerie, and it haunts the book, a spectral and baneful presence.)

After his success Capra was plagued by feelings of guilt and unworthiness that took many physical as well as emotional forms (though he died only about a year ago, at the age of 94). During the 40s his career suffered a sudden and precipitous decline from which it never recovered, though interest in his work was revived with the publication of his autobiography. (It’s important to bear in mind that It’s a Wonderful Life — his most famous and cherished movie today — was a resounding commercial flop when it came out in 1946.) But before, during, and after this decline his reputation as a leftist, humanist, and creative genius who stood alone remained virtually impregnable, despite evidence to the contrary that McBride has consolidated and expanded. (One of his most surprising revelations involves Capra’s unsavory behavior during the McCarthy witch-hunts of the early 50s — he secretly informed on the leftist screenwriters who were mainly responsible for the populism of his movies during the 30s and 40s. It’s a grim commentary on the paranoia of that period that a conservative patriot like Capra, who sincerely devoted himself to producing wartime propaganda, was threatened and terrorized into cowardly behavior by the red-baiters.)

Some reviewers of McBride’s book have complained that he has an ax to grind in painting so unsympathetic a picture, but overall his approach strikes me as far more convincing than, for example, Donald Spoto’s highly censorious treatment of Alfred Hitchcock in The Dark Side of Genius. As I see it, McBride’s aim is less to point fingers than to provide a deeper understanding of how and why our political prejudices and assumptions get formed. Ultimately the target is not so much Capra as those aspects of the American character, including political innocence, that make Capra’s pictures characteristic of and attractive to our culture.

Recently McBride wrote a review of Patriot Games for Variety that dared to attack the movie’s politics — a position deemed so out-of-bounds by the studio that it promptly withdrew its advertising from the newspaper. The fact that McBride was the only reviewer to bring up the film’s politics made his comments automatically enlightening, but he was clearly violating a central taboo in contemporary film reviewing by assuming that a movie has political meanings and a political impact in the first place. His Capra book is both shocking and useful for similar reasons.

The most eloquent defenders of Capra’s populist pictures, critics such as William S. Pechter and Charles Wolfe, focus on the keen sense of desperation lurking behind all the success stories. The fact that these desperate fears and hopes were formed mainly during the Depression is central to the historical significance of Capra’s work, yet the best movies of Preston Sturges — which appeared during the 40s but were no less affected by the Depression — show that there was a viable artistic alternative to dealing with many of the same issues. A highly interesting study might be done of the different uses these directors made of the Dickensian character actor Raymond Walburn — by Capra in Broadway Bill, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town [see first still below], State of the Union, and Riding High, and by Sturges in Christmas in July [see second still below], Hail the Conquering Hero, and The Sin of Harold Diddlebock. (By and large I find Walburn lovable in the movies of both, but more cynical in the Capra pictures.)

In Broadway Bill Walburn plays seedy Colonel Pettigrew, the hero’s conniving crony who courts his landlady (Margaret Hamilton) in order to squeeze money out of her. The hero, Dan Brooks (Warner Baxter), is the disgruntled son-in-law of a small-town tycoon (Walter Connolly). He leaves his wife Margaret (Helen Vinson) and his job as factory vice president to enter his racehorse, Broadway Bill, in a $25,000 handicap. The colonel’s conning of the landlady is only one of many schemes they hatch to get Broadway Bill into the race. Two other important allies in the cause are the black groom Whitey (Clarence Muse) and Margaret’s spunky kid sister Alice (Myrna Loy), who turns up to deliver a rooster named Skeeter to cure Bill of his homesickness and sticks around to provide romantic interest.

The movie is full of desperate scams, con games, and last-ditch efforts that wind up rebounding on their perpetrators, and after reading McBride’s biography it’s difficult not to read these aspects of the plot as variations on the ongoing predicaments of Capra’s own career. At one point Whitey shoots craps with loaded dice in order to raise money, then gets beaten when he’s caught. (A literal punching bag throughout, Whitey is the kind of obsequious comic scapegoat that can only make us wince today; we’re supposed to be amused when Dan brusquely strips him of his savings in order to enter Bill in a race. Like many other secondary cast members, including Walburn and Hamilton, Muse returned to play his original part in Riding High, which laid on the racial stereotyping nearly as thick but cut back on the physical abuse.) Shortly afterward the colonel and a helper con a hayseed at the racetrack out of $25 for a betting tip, setting off a chain reaction of rumors that eventually get back to the gullible colonel, who bets on the losing horse himself: “Milked by my own chicanery,” he wryly notes.

One probable reason, aside from its relative unavailability, that Broadway Bill has been less celebrated than other Capra pictures of this period is the fact that Warner Baxter is less memorable than Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, or James Stewart. Although he was once prominent as a classic working-class hero, the Cisco Kid, Baxter is barely known today, which means that we’re less likely to respond to his unfamiliar gruff and spiky style — throwing rocks at a messenger, punching Whitey, taking money out of Alice’s purse — with the sort of warmth and indulgence we feel toward Capra’s better-known male stars.

Another factor that distances the movie from star-struck contemporary culture is that its spirit and energies are often more collective than individual, and in this respect perhaps even more evocative of the Depression than Capra’s better-known pictures. For related reasons the locations are somewhat more specific and resonant than they usually are in Capraland: much of the picture was shot at the Tanforan racetrack near San Francisco, and the gradual domestication of a leaking barn where Bill is stabled becomes central to both the plot and the developing love story, evoking the archetypal Depression love story of the previous year, Man’s Castle.

The movie’s best sequence, beautifully composed and edited, is a brilliant set piece in which a $2 bet placed on Bill by a famous millionaire sets off a chain reaction that spreads from telephone switchboard to barber shop and across the city, and the odds are lowered from 100 to 1 to 60 to 1 when crowds storm the racetrack’s ticket windows. If memory serves, none of the principal members of the cast appear in this syncopated montage, and thanks to the pile-driving momentum, they aren’t missed.

Capra’s skill with bit players here is as important as his handling of stars elsewhere; he builds suspense at key moments with a fleet rock-skipping effect in the editing rhythms, which can only be brought about through careful attention to incidental details. Of course most or all of these montage sequences were scripted — by Robert Riskin, whose original script adapted a story by Mark Hellinger, and possibly also by Sidney Buchman, who is not credited but was brought in to write new scenes after Capra decided to give Riskin’s script a different ending. (Readers who don’t want to learn about the ending should check out here.)

According to McBride, Capra often fostered the impression that he had more to do with his scripts than was actually the case, but McBride and other sources confirm that Capra was responsible for this picture’s startling climax — Broadway Bill dies of a heart attack at the very instant he wins his final race. This may be the most succinct rendering of the “catastrophe of success” anywhere in Capra’s work, and it sets off disquieting ripples that affect the picture retrospectively as well as undermine the utopian goodwill and vintage Capracorn of the final sequence (set two years after the funeral for Bill at the racetrack). While a hapless Sturges hero may plummet from the heights to the depths and be tossed back up over the course of a picture, Capra’s title nag gets to the starting gate only by means of a protracted series of lies and scams, and then, with everyone’s pious blessing, wins and perishes in the same breath.