From the Soho News (December 23, 1980). — J.R.

“This film was made in violent contrast to Citizen Kane,” François Truffaut once wrote of The Magnificent Ambersons, Orson Welles’ second feature, “almost as if by another filmmaker who detested the first and wanted to give him a lesson in modesty.” In comparable fashion, Alain Resnais — a rationalist surrounded by surrealist nightmares — has often described some of his films as being made in reaction (and contradistinction) to the ones that preceded them.

Thus the subjective, highly mobile camera of the apolitical Last Year at Marienbad (1961) was countered by the objective, stationary camera setups and political contexts of Muriel (1963). And similarly, the proliferating dreamlike fictions and Lovecraftian enchantments of Providence (1977) have led to the documentary, demonstration-style demeanor and scientific wit of Mon Oncle d’Amérique (1980), his latest film — a movie that also attempts to combine elements from his nonfiction shorts and previous fictional features.

It’s been seven years since I last interviewed Resnais — on a soundstage at Epinay-sur-Seine, a Parisian suburb where he was shooting Stavisky… Greeting him recently at his Park Lane suite, I still found him almost awesomely handsome at 58, and no less delicate, modest, and cordial in his manner, despite a continuing shyness that he has come some distance in mastering. He bravely resolved to speak in English throughout the interview.

***

At Epinay-sur-Seine, I asked you about your current projects, and you mentioned a long documentary with the biologist Henri Laborit about the mechanics of the brain. How did the project develop from there?

There was a French laboratory that said they had discovered a drug which enhances memory, and they asked Laborit to write a screenplay about memory. He said, “I’ll do it, but only if somebody like Alain Resnais directs it.” Maybe it was a joke, but someone called me anyway and said, “Would you meet Henri Laborit?” And I said, “Of course” — I’d read some of his works and some interviews with him in magazines that I’d found very interesting.

We had lunch with people at the laboratory, and we discovered by the time we were having desserts that they had enough money to pay for the lunch, but not enough to produce a documentary of any kind! So the project didn’t jell, but I had met Laborit; and we took the habit to have lunch at his home with his family, two or three times a year, at which times we talked about what might be interesting about making a long feature together. It would be possible to make a short film, but maybe a feature would be easier to raise the money for.

We talked about ideas like the story of the cell through the ages, things like that, but nothing really came out of it. I directed other pictures, Stavisky… and Providence, and during that time my wife, who is an assistant director and worked for François Truffaut, knew Jean Gruault, who was the screenwriter on Jules and Jim, and said we should meet. Jean Gruault had a lot of old films — silent films by Griffith and Frank Borzage — and he showed these to me, and we became friends.

One day I said, “Don’t you think it would be fun if you’d agree to write a screenplay in which we would do the opposite of what’s done in Hollywood, when there are messages or a thesis? Not to hide the didactic part of the film, by trying to put it in the mouths of the characters, but just putting it alongside the story, so that we’d have a film with fictional characters, and at the same time Henri Laborit would talk and comment on the actions of the characters.”

I’ve been reading a translation of Laborit’s La Nouvelle Grille (1974) that’s been published here, by St. Martin’s Press.

Yes, Decoding the Human Message. It’s good that you have it, because, after all, the film is only a comedy. We made it a kind of comedy, because we were conscious that we weren’t going to explain the human condition in two hours. But the most interesting things that Laborit has discovered are in the book, not in the film. Because what we could not use in a dramatic structure was eliminated.

I knew that the film would be called Mon Oncle d’Amérique, and that there would be accordion music on the soundtrack, but that’s all I said to Jean Gruault. After six months, we established a first draft — much longer than the film you have seen — and brought this to Laborit. He said, “Well, I’m not a filmmaker or a film critic, I don’t know exactly what you intend. But if you need me, I’m available.”

He was very generous. What’s important about Henri Laborit is that he doesn’t pay attention to his reputation — because it’s dangerous for a scientist to be mixed up with a film. I’m sure that a lot of his colleagues would say that it’s not right for a scientist to do that kind of thing. But Laborit doesn’t care — he’s kind of marginal and freelance.

So we shot all the fiction part of the film, and left spaces in the script for Laborit to talk. Then we shot for two days with Laborit, but he was just improvising: he didn’t know the film, he’d only read the story a year before. We just came and I asked him some questions, as you’re doing with me, and afterward I went back to the editing room with the film.

Then we showed the complete film to Laborit. We were very nervous, because he could have said, “That’s not my work.” But he was very generous, he said, “Of course I feel frustrated in a way, but it’s not a film about Laborit or a digest of my work. So if you’re happy with that, I’ll give you my approval.” So we kept the film as it was, knowing that it was very incomplete.

***

Would you say that Mon Oncle d’Amérique is any more French than your other films?

(Laughs.) Yes, it’s funny that you say that. It’s true that during the writing and the shooting, I was always saying to my friends or to the crew, “Providence was an Anglo-Saxon film, but this time we are making un film franchouillard — I don’t know how you call that in English, it’s slang that means very, very French. I think we always had in mind that everything should be typical of French habits: the French way of speaking, dressing, eating, drinking —

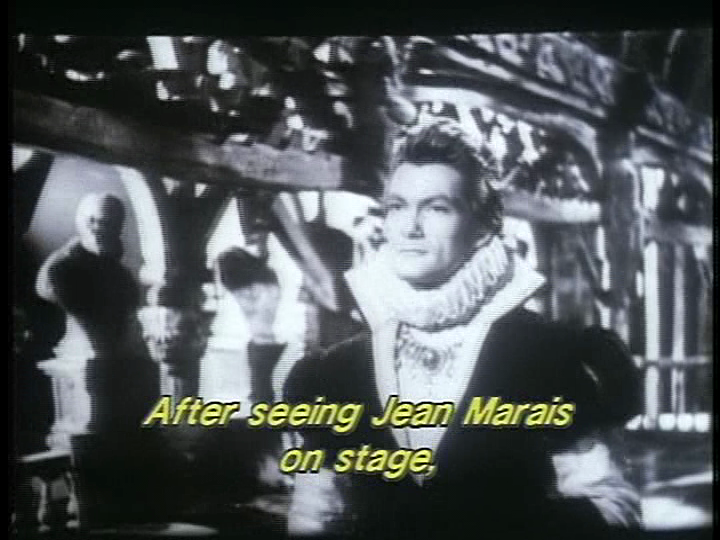

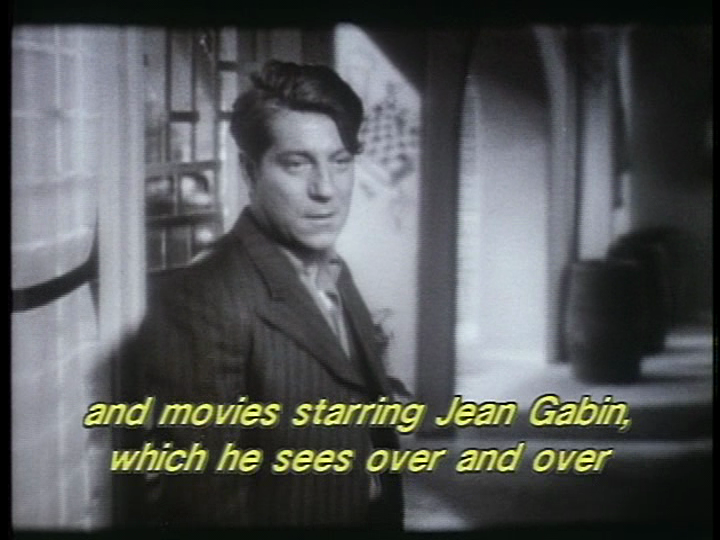

Even the use of French movie stars — Danielle Darrieux, Jean Marais, and Jean Gabin — in all those films clips used to represent used to represent the leading characters’ ideal images of themselves.

Yes, for me that was the French gesture!…Je t’aime, je t’aime was Belgian for me. And maybe another one, Muriel, ou le temps d’un retour, was French in the same way.

It’s true that meals play a decisive role in both films! One thing that’s interesting about these clips isthe fact that two of the three central characters model themselves on stars of the opposite sex — Jean Le Gall (Roger-Pierre) on Darrieux, and Janine Garnier (Nicole Garcia) on Marais. Do the clips that show Darrieux and Marais together all come from Ruy Blas, the costume film that Cocteau scripted?

Yes, I think so. Thy were together in at least four or five films, but we didn’t have a big choice. I think there are 26 clips in the film. And if the producer were here today, I am sure he would tell you that there were fewer problems with shooting the entire film than with trying to get those clips. You can’t imagine how difficult it is to get the old prints and get the rights — because so many people have them, and sometimes you have to resort to blackmail to get them.

How much of the film was shot in a studio?

Nothing at all, alas, because we didn’t have enough money. I lik working in studios because the sound is better than on locations. Sometimes, of course, we changed the color of the walls, or added walls and rebuilt.

It seems like the critical reception of this film is much more favorable than that of Providence, a film I like very much.

It depends on which country. Because Providence was very well received in Europe — including London, where it ran more than nine months in the same theater — but it was not well received in New York. Mon Oncle d’Amérique had very mixed reviews in France, but the audience came. From the commercial point of view, it is my first hit, I would say.

Everyone has been very surprised — the producer, myself — because when we were making the film, we were conscious that maybe it wouldn’t work for the audience, that even if it had interesting reviews, that might not be sufficient. But the reviews were mixed between very good and very bad, and I’ve never had a film as successful in France. That’s all I’m saying; I’m not telling you that I’m proud or anything like that.