From the September 1, 1994 Chicago Reader.

One of Frederick Wiseman’s strongest documentaries, this nearly three-hour look at a New York welfare center (1975), which concentrates on the interactions between clients and social workers, is both pungent and unbearable in its depictions of frustration and anger on both sides of the counter. Wiseman’s customary refusal to add an offscreen commentary makes the film even more compelling, though it may irritate viewers who feel they need to know more about the cases to decide how they feel about them. Throwing us into the thick of things without a map, Wiseman dares us to reach conclusions according to the evidence of our eyes and ears. It’s impossible to emerge from such an experience unscathed. 167 min. (JR) Read more

From the November 6, 1998 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This in-depth 1997 look at everyday life in Chicago’s Ida B. Wells housing project, running 195 minutes, is one of Frederick Wiseman’s greatest documentaries to date. Few of the points in its epic analysis are obvious ones; though it gives the overall impression that public housing is like living in a concentration camp, the film favors exploration and understanding over finger-pointing and polemicizing. Wiseman presents a wide array of materials, and because you have to reflect on the film to realize how the various pieces of its design hang together, you’re liable to be thinking about it for months afterward. Wiseman will attend the screening, and the following afternoon, Saturday, November 7, at 1, he’ll take part in a panel discussion at the Film Center chaired by Studs Terkel and featuring CHA and other officials. Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Friday, November 6, 6:00, 312-443-3737. –Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1999). — J.R.

I recently heard about an American teenager visiting Wales who insisted on calling the Welsh people she met English. When it was pointed out to her that the Welsh didn’t like being identified that way, she said she was sorry but that’s what she’d been taught in school — and it would be too complicated for her to change what she called them.

Given the isolationism of Americans, which seems to grow more pronounced every year, an event like the Chicago International Film Festival has to be cherished. This year it’s offering the city 108 features from 31 countries — 32 from the U.S. and 76 from elsewhere, 49 of them U.S. or North American premieres, as well as five programs of shorts and five tributes. Consider them cultural CARE packages, precious news bulletins, breaths of fresh, or stale, air from diverse corners of the globe — even bad or mediocre foreign movies have important things to teach us. However you look at them, they’re proof that Americans aren’t the only human beings and that the decisions Americans make about how to live their lives aren’t the only options — at least not yet. Read more

Commissioned in December 2008 by London’s National Film Theatre or the South Bank — I can’t recall now which of these appellations it was using then — for a small Burnett retrospective. These notes were written according to precise specifications, as indicated in the word lengths mentioned below. — J.R.

1. 35-word stand first

Versatile yet focused, Charles Burnett offers an in-depth portrait of the ghetto community he grew up in, South Central Los Angeles, in an oeuvre that’s both witty and tragic, continuing to expand and surprise us.

2. 350-word introduction

Born in Mississippi in 1944 but raised in Watts, Charles Burnett is a filmmaker as steeped in his community as William Faulkner was in his. But he hails from an invisible community, so it shouldn’t be surprising that one of the supreme living masters of American cinema should also be among the slowest to gain recognition.

That he’s worked memorably for both Miramax (The Glass Shield, 1994) and the Disney channel (Nightjohn, 1996) has only helped to give him a scattered and confused mainstream profile, typically omitting such bold independent experiments as The Final Insult (a 1997 digital video about the homeless, mixing documentary, fiction, and poetry) and Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (a 2003 TV essay that fictionalizes and dramatizes many conflicting versions of its title figure — a Virginia slave who led a 1839 revolt that slaughtered 59 whites). Read more

The fifth chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). As James Naremore aptly notes about my work in his collection An Invention Without a Future: Essays on Cinema (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 2014), I have revised my attitudes towards watching films on home video formats considerably since I wrote this over a decade and a half ago. -– J.R.

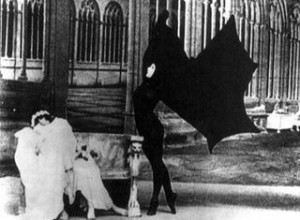

In 1998, Water Bearer Video issued in a boxed set of four cassettes the complete ten-episode silent French serial Les vampires. Directed by Louis Feuillade in 1915 and 1916 and starring the great actress Musidora as the mysterious Irma Vep, this monumental and exciting crime fantasy is one of the key works in the history of cinema — seminal in its influence on moviemaking as a whole, and to my mind considerably more watchable, pleasurable, and even modern from certain perspectives than the contemporaneous long features of D. W. Griffith, The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Yet astonishingly, this major work had been unavailable in the United States for over eighty years, ever since it ran commercially as a serial in American movie houses; apart from a few exceptional archive and festival showings from the sixties onward, not a single episode was distributed in any form. Read more

From the September 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

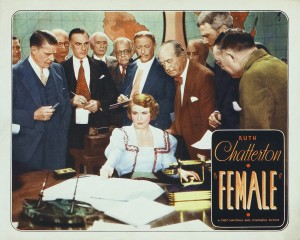

Ruth Chatterton and George Brent, a real-life married couple at the time of this 1933 feature, star as the tyrannical head of a major auto company and the independent-minded guy who comes along to challenge her and win her heart. Before it (and its heroine) abjectly cop out in the closing minutes, this hour-long precode feature offers a bracing feminist fever dream of a young woman commanding a huge corporation and a stable of attractive young men, whom she invites over to her house for one-night stands. Breezily directed by Michael Curtiz and William Dieterle; with Johnny Mack Brown, Ruth Donnelly, and some very sumptuous set design — Depression fantasy of the good life at its most hyperbolic. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From American Film (November 1981). — J.R.

Old Wave Saved from Drowning

By Sandy Flitterman and Jonathan Rosenbaum

Think of French cinema, and the New Wave springs immediately to mind. This association is hardly accidental. History, it is often said, gets written by the victors. And the victories recounted in the standard film histories — whether they are critical successes or box-office triumphs — are inevitably at the expense of other movies, individuals, or social trends that presumably failed to scale the same heights.

But the New Wave, like other movements in film history, is significant not only for what it gave us — films like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Godard’s Breathless, and Resnais’ Hiroshima, mon amour — but also for what it took away, for the films it rebelled against, repudiated, buried in the dustbin of history. Now a fascinating new program of forty-six subtitled French films made between 1930 and 1960 helps sketch out the rudiments of just such an alternative history.

This group of films, appropriately entitled “Rediscovering French Film,” has been put together by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in cooperation with the French government and, after premiering in Manhattan this month, is scheduled to travel next year to Washington, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Houston, and Chicago. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 3, 1989). Twilight Time has recently (2014) released this film on Blu-Ray, with many extras. — J.R.

The point of director Jimmy Murakami and screenwriter Raymond Briggs’s rather original English animated feature is to get us to think the unthinkable — to imagine the aftereffects of a nuclear holocaust. But rather than force this bitter pill on us, they create a very funny and believable elderly English couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs. These two are still mired in memories of World War II, but when nuclear war hits they are eager to do all the proper things and to follow the instructions in the government booklets correctly. Rather than stretch this fable out to a global scale, the filmmakers make all their essential points by sticking to this isolated couple in their country cottage, following them step-by-step through the experience. Aided by a realistic style of animation that incorporates some live action, by occasional stylistic changes that allow for more abstraction in some fantasy interludes, and by the expert speaking voices of John Mills and Peggy Ashcroft, the movie succeeds impressively. It’s rare that a cartoon carries the impact of a live-action feature without sacrificing the imaginative freedom of the pen and brush, but this one does — and does so well that we are even persuaded to accept the didactic framework. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 21, 2005). Alas, I’ve never been any sort of Shakespearean scholar, and if I’d read the devastating take-down of this film by Ron Rosenbaum (no relation) in The Shakespeare Wars, published the following year, I’m sure I would have been far less tolerant….It’s worth adding, however, that Ron Rosenbaum isn’t any sort of Orson Welles scholar when he accepts the 1997 version of his Othello as a “restored” version — or when countless other commentators call the 2014 perpetuation of that version, with Welles’ own choices of music and sound effects replaced by uninformed simulations, any sort of “restoration”. (Welles’ own two versions of Othello — that is to say, with his own soundtracks — were thoroughly suppressed until Criterion eventually released them both.) — J.R.

Director Michael Radford (Nineteen Eighty-Four, Il postino) begins his adaptation of the Shakespeare play with a precise date and a brief documentary about anti-Semitism in 16th-century Venice; this doesn’t have much to do with the playwright or his audience, but it provides a social context for what follows. Al Pacino avoids his usual bombast, giving his Shylock some shading, and Jeremy Irons is fine as Shylock’s legal opponent, Antonio. Read more

It was shocking to learn that Harun Farocki (January 9, 1944 – July 30, 2014) died at the age of only 70. According to Artnet, he made over 90 films. He will be sorely missed.

From the Chicago Reader (February 14, 1992). — J.R.

FILMS BY HARUN FAROCKI

The paradox is that Farocki is probably more important as a writer than as a filmmaker, that his films are more written about than seen, and that instead of being a failing, this actually underlines his significance to the cinema today and his considerable role in the contemporary political avant-garde. . . . Only by turning itself into “writing” in the largest possible sense can film preserve itself as “a form of intelligence.”

— Thomas Elsaesser, 1983

The filmography of Harun Farocki — a German independent filmmaker, the son of an Islamic Indian doctor — spans 16 titles and 21 years. To the best of my knowledge, only one of his films (Between Two Wars) has ever shown in North America before now. A traveling group of 11 films put together by the Goethe-Institut began showing in Boston last November and this April will reach Houston, the last of the tour’s ten cities. Read more

A reprint from the Taipei Times (October 13, 2014), with different illustrations. For the record, I don’t think it was betel nuts that I was chewing at Hou’s 1991 party; what I recall was a kind of barklike Taiwanese form of speed. — J.R.

Narrating Taiwanese identity

The Hou Hsiao-hsien retrospective at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image educates American film buffs about Taiwanese history and identity

By Dana Ter / Contributing reporter in New York

The year was 1991. American film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum was experiencing his first authentic night out in Taipei at a late night karaoke party hosted by renowned Taiwanese film director Hou Hsiao-Hsien (侯孝賢). Fueled by bottles of cognac and a generous supply of betel nuts, the duo belted out Beatles songs until 3am before stumbling home.

Having reviewed Dust in the Wind (戀戀風塵, 1986) and A City of Sadness (悲情城市, 1989) for the Chicago Reader, long-time film critic Rosenbaum was no stranger to Hou’s work. But being in Taipei for the Asia-Pacific Film Festival gave him a better appreciation of the local culture, history and setting.

“I was able to spend my 19 days there less as a tourist than as a part of everyday life in Taipei,” said Rosenbaum, who was in New York this past week for the retrospective “Also Like Life: The Films of Hou Hsiao-hsien” at the Museum of the Moving Image. Read more

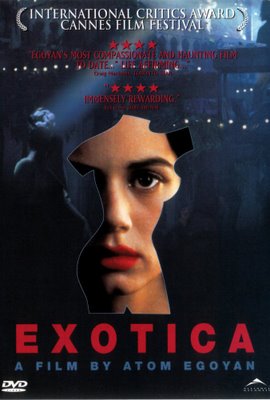

From the Chicago Reader, March 17, 1995. — J.R.

Exotica

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Atom Egoyan

With Bruce Greenwood, Elias Koteas, Mia Kirshner, Don McKellar, Arsinee Khanjian, and Sarah Polley.

The saddest parts of Exotica — Atom Egoyan’s lush and affecting sixth feature, a movie inflected like its predecessors by obsessive sexual rituals and desperate familial longings — are moments when money awkwardly changes hands. This film is every bit as allegorical as his Speaking Parts, The Adjuster, and Calendar — and every bit as concerned with a need for family surrogates as Next of Kin and Family Viewing — but it is only incidentally a movie about capitalism and its ability to pervert personal relationships. It does involve voyeurism, corruption, and a form of prostitution; all these things are conventionally associated with capitalism, but they’ve been around much longer.

Exotica has plenty to say about the modern world, including the psychological, social, and racial (even colonial) ramifications of “exotic” sexual tastes, but class difference isn’t a significant part of its agenda either. The personal and professional links forged between individuals — and there are very few relationships in this movie that aren’t both personal and professional — all seem predicated on forms of barter, as well as the assumption that everyone is, or eventually becomes, either a substitute for a missing family member or a virtual double for someone else. Read more

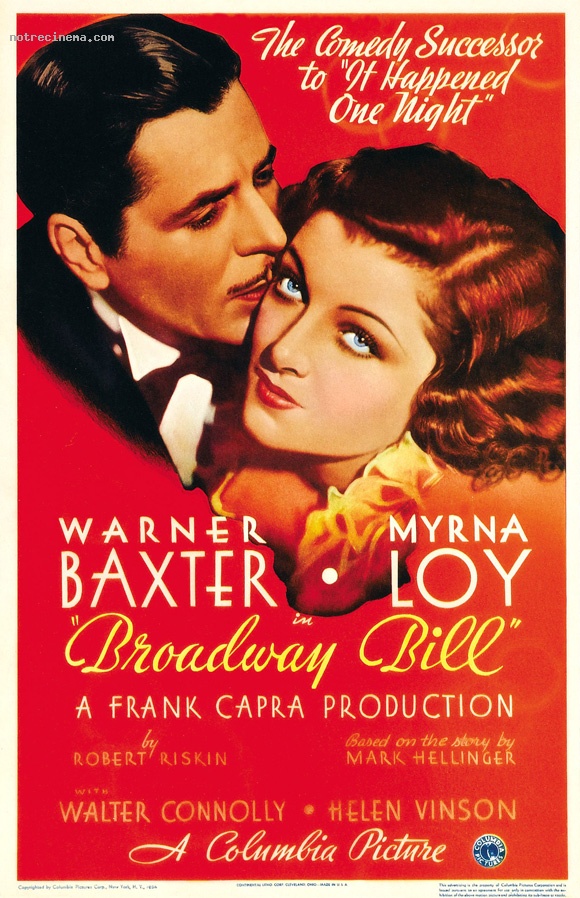

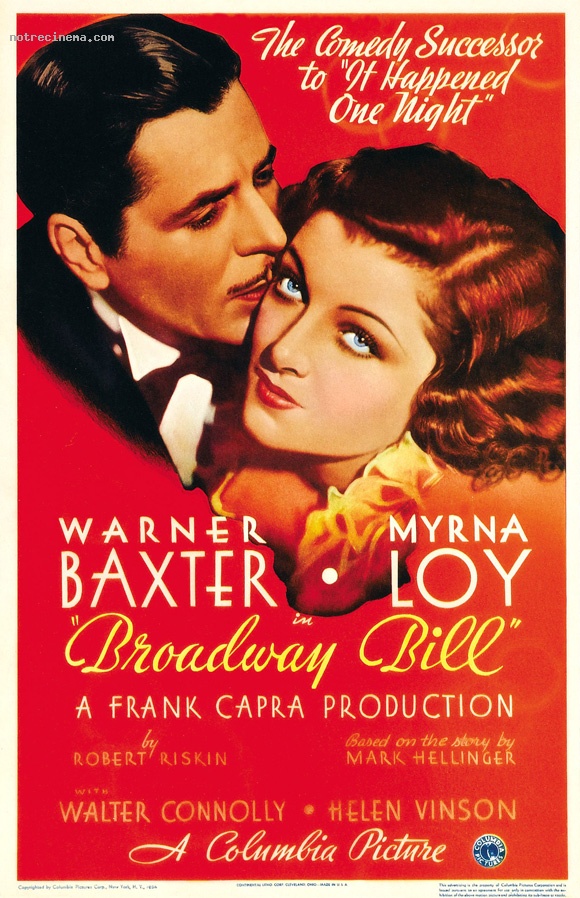

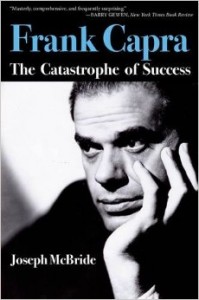

This review of Frank Capra’s Broadway Bill (1934) first appeared in the August 7, 1992 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

BROADWAY BILL

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Frank Capra

Written by Robert Riskin and Sidney Buchman

With Warner Baxter, Myrna Loy, Helen Vinson, Clarence Muse, Raymond Walburn, Walter Connolly, Margaret Hamilton, and Frankie Darro.

Though it’s surely a coincidence, the theatrical rerelease of Frank Capra’s Broadway Bill and the simultaneous publication of Joseph McBride’s Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success are mutually enhancing in a number of ways.

Capra’s 1934 Christmas release was made for Columbia, bought by Paramount, and withdrawn from circulation over 40 years ago, when Capra was preparing a remake called Riding High (1950) — a Bing Crosby musical with virtually the same plot and dialogue that was so unmemorable that despite numerous TV screenings the film critic for the Boston Globe claimed last month that it had never been made at all. The much feistier Broadway Bill, by contrast, has never turned up on TV, and apart from a few archival airings has remained unseen for over half a century. A breezy if edgy racing comedy laced with some serious ingredients, it isn’t nearly as good as The Bitter Tea of General Yen or It Happened One Night, both of which preceded it, but on the other hand it isn’t as cloying as the worst parts of its successors Mr. Read more

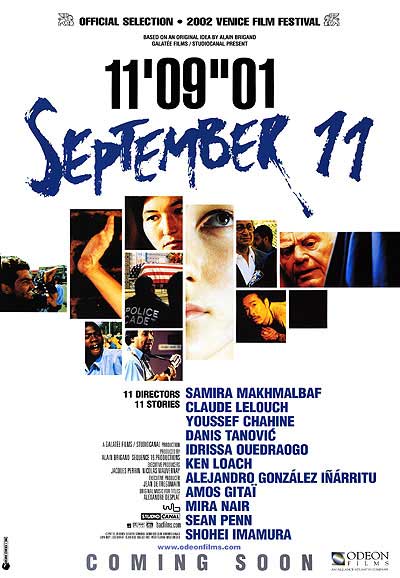

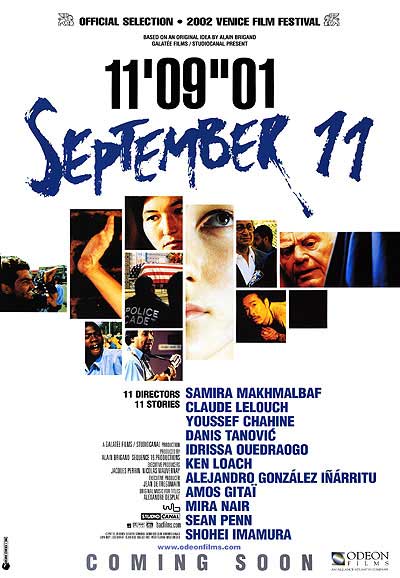

From the Chicago Reader (September 5, 2003). — J.R.

September 11

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Samira Makhmalbaf, Claude Lelouch, Youssef Chahine, Danis Tanovic, Idrissa Ouedraogo, Ken Loach, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, Amos Gitai, Mira Nair, Sean Penn, and Shohei Imamura

Written by Makhmalbaf, Lelouch Chahine, Tanovic, Ouedraogo, Paul Laverty, Vladimir Vega, Gonzalez Inarritu, Gitai, Marejos Sanselme, Sabrina Shawan, Penn, and Daisuke Tengan.

It was probably inevitable that the terrorist attacks of September 11 were immediately seen as a blow against America rather than as crimes committed against humanity, the world community, or even just the people, many of whom were not American, who happened to be occupying three particular buildings. We deduced from the reported beliefs and intentions of the terrorists that America and what it represented to them was the desired target. But the willingness to privilege this vision over every other possible understanding of the tragedy may be dangerous. It even suggests a certain ideological defeat, because it has allowed the enemy to set the terms of the conflict.

The reflex is understandable. “Humanity” and “world community” are abstract. “America” is also abstract but feels closer to home. Because it’s familiar, it’s treated as if it were the only reality, as if it were, in fact, the world. Read more

A program note for the Pacific Film Archive, April 5, 1983, to launch a program I selected entitled “Institutional Qualities and Casual Relations: The Avant-Garde Film Today”, put together with the help of Edith Kramer. Most of the films in the series were related to both my book Film: The Front Line 1983, published around the same time, which includes separate chapters on both Sara Driver and Leslie Thornton, and the two courses I was teaching concurrently as visiting professor at the University of California Berkeley Film Studies Department. — J.R.

You Are Not I and Adynata 7:30

Two very different and accomplished films about female identity, Sara Driver’s You Are Not I (1981, 50 min.) and Leslie Thornton’s Adynata (1983, 30 min.) are both dialectically conceived; there the resemblance ends. The first is a very close adaptation of a Paul Bowles story written in the late 1940s, filmed in black and white [cinematography by Jim Jarmusch], about a psychic and territorial war fought between two sisters, one of them a schizophrenic. The second is a non-narrative film about the ideological configurations and semiotic constructions of the East as seen by and filtered through the West, particularly in relation to the female figure — articulated through many different kinds of found material and variable film stock. Read more