From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975, Vol. 42, No. 500. — J.R.

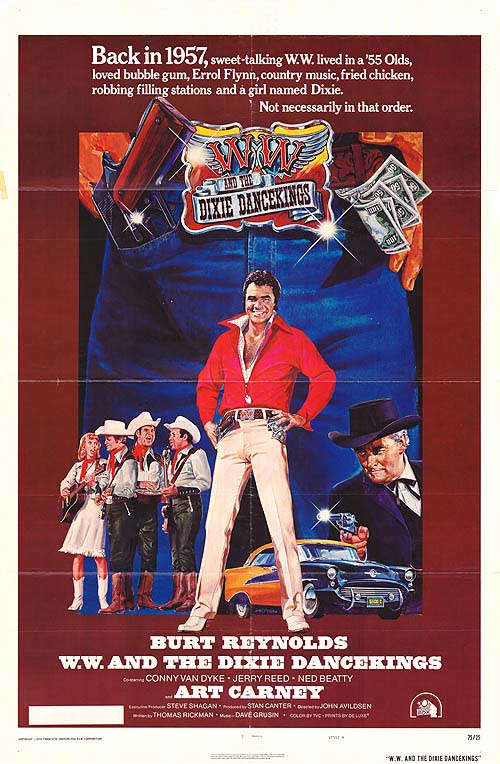

W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings

U.S.A..1975

Director: John G. Avildsen

Cert—A. dist–Fox-Rank. p.c–20th Century-Fox. exec. p–Steve

Shagan. p–Stanley S. Canter. p. manager–William C. Davidson. asst. d

–Ric Rondell, Jerry Grandey. sc–Thomas Rickman. ph–Jim Crabe.

col–TVC; prints by DeLuxe. ed–Richard Halsey, Robbe Roberts. a.d—

Larry Paull. set dec–JimBerkey. sp. effects–Milt Rice. m–Dave Grusin.

songs–“Hound Dog” by Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, sung by Elvis

Presley; “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight” by Calvin Carter, James

Hudson; “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry; “Bye Bye Love” by

Felice Bryant, Boudleaux Bryant; “I’m Walkin’” by Antoine “Fats”

Domino, Dave Bartholomew; “Blue Suede Shoes” by Carl Lee Perkins;

“Mama Was a Convict” by Tom Rickman, Tim Mclntire; “A Friend” by

Jerry Reed; “Dirty Car Blues” (traditional), performed by Furry Lewis.

cost–Dick LaMotte. titles–PacificTitle. sd. rec–Bud Alper. sd. re-rec—

Don Bassman. stunt co-ordinator–Hal Needham. l.p–Bert Reynolds

(W.W. Bright), Art Carney (Deacon John Wesley Gore), Conny Van Dyke

(Dixie), Jerry Reed (Wayne), Ned Beatty (Country Bull), Richard D.

Herst (Butterball),Don Williams (Leroy), Mel Tillis (lst Good Ole Boy),

James Hampton (Junior), Furry Lewis (Uncle Furry), Sherman G. Lloyd

(Elton Bird), Mort Marshall (Hester Tate), Bill McCutcheon (2nd Good Ole

Boy), Peg Murray (Della), Sherry Mathis (June Ann), Roni Stoneman

Hemrick (Ticket Lady), Charles S. Lamb (Dude), Nancy Andrews (Rosie),

Tootsie (Herself), Shirlee Strother (Secretary), Virgilia Chew (Elton Bird’s

Secretary), Stanley Greene (Chauffeur Powell), Frank Moore (June Ann’s

Boss), Fred Stuthman (Sourface), Cathy Baker (1st Dixiebelle), Heidi

Hepler (2nd Dixiebelle), Polly Holliday (Mrs. Cozzens), Lorene Mann

(1st Delorosa Sister), Rita M. Figlio (2nd Delorosa Sister), Sudie Callaway

(3rd Delorosa Sister), Mickey Salter (1st Elvis), Hal Needham (Trooper

Carson), Gil Rogers (Street Preacher), Gil Gilliam (Boy with Radio).

8,161 ft. 91 mins. Original running time–94 mins,

The mid-1950s. After holding up a Southland Oil petrol station

in Georgia, good-naturedly giving part of the take to the attendant

to keep him quiet, and subsequently fleeing from the police, W.W.

Bright enters a gym where a dance is being held and quickly takes

over the bandstand as emcee, gaining the co-operation of the band

— Dixie and the Dancekings — when a policeman arrives. Claiming

to be a successful country music promoter, W.W. next insists on

taking the group to an ‘audition’ in Tennessee in Rosie’s Nashville

Corral. The night-club proves to be a sleazy dive and no job offers

are forthcoming, but W.W. persuades the group to trust him as a

manager — after making an unsuccessful pass at Dixie — and holds

up another Southland Oil station, bribing the attendant as before.

Meanwhile Elton Bird, president of Southland Oil, hires former

lawman Deacon John Wesley Gore to track down the person

holding up his stations across the country. W.W. buys outfits for

the band and abortively tries to hold up another station; the

attendant gives Gore a description of W.W., his black and gold

Oldsmobile and the band, which Gore reads on a radio revival show.

W.W. takes the band to Opryland and then tries to persuade one

of the singers, Country Bull Jenkins, to write a song for the group,

but changes his mind when Jenkins shows too much interest in

Dixie. After failing in his attempt to hold up a drive-in bank, W.W.

hides out with the band in Alabama, in the shack of Negro blues

singer Uncle Furry; W.W. burns his car and narrowly escapes Gore.

Because his robberies are endangering the band, W.W. decides to

leave, but has second thoughts after Dixie offers to sleep with him

and he hears the group playing again. He takes them to Nashville,

persuades Jenkins to let them perform at Opryland, and is then

arrested by Gore. But Gore lets him go just as they arrive at the

police station: it is just past midnight, Sunday morning, and Gore

is too religious to turn in someone on the Lord’s day.

For all its corny car chases, flashy optical transitions and silly

plot expediencies (like the incredible reprieve granted the hero at

the end), W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings conveys an unmistakable

affection for its title characters, milieu and period that is as

unexpected as it is refreshing in this branch of semi-computerised

cinema. Taking charge with an impeccable Southern accent, Burt

Reynolds establishes W.W.’s credentials as a hillbilly Robin Hood

in the opening scene, when he lackadaisically holds up a filling

station while retaining the good will of the attendant with cheerful

sympathy and a bribe (“My daddy said there are two thangs that

keep the world go-in — one is need an’ one is greed”); only later do

we discover that his robberies of Southland Oil stations and his

instant rapport with the attendants stem from his once holding the

same job himself. A good-natured con artist is, of course, an essential

part of the Reynolds persona; what largely distinguishes the role

here is its location in a place and time (Deep South, early Elvis)

that can sustain it in social terms — as the high-flown hope of the

hopeless — without the accompanying misogyny, cynicism and

violence of a Robert Aldrich context. Veering in the opposite direction

from The Mean Machine, W.W. may occasionally sin on the sticky

side, but it yields a lot of indelible local flavour along the way:

hand-stamping for identiflcation purposes at a small-town dance;

W.W. expounding on the merits of Errol Flynn in The Sun Also

Rises to his date at a drive-in; his tear-jerking speech about Koreawhen Leroy

remarks, “You talk lak one-a them Communists or somethin’ “; Dixie’s proud

assertion of her sexual selectivity; Furry Lewis’ wonderful “Dirty Car Blues”, and the

ceremonial, quasi-religious burning of the sacred Oldsmobile that follows. The

mystique of performing in Opryland is realised much more concretely here than in

Nashville (with its very different virtues), precisely because it is recognised and

honoured on its own terms and not as the emblem of some higher order. Only Art

Carney — distinctly out of his element as the fanatical Deacon, and evidently

bewildered by the ethnic trappings of his villainous part — seems foreign to the

warm spirits, graceful interplay and authenticity of this likeable down-home farce.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM