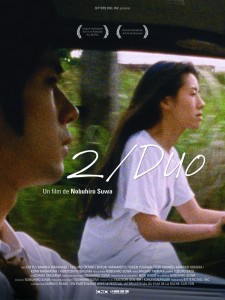

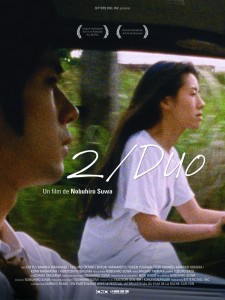

From the February 26, 1999 Chicago Reader. July 2014 postscript: This fascinating and neglected film, still my favorite among the Nobuhiro Suwa features that I’ve seen, has become available on a French DVD released by Capricci — see the first image below — albeit with (optional) French subtitles only. — J.R.

2/Duo

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nobuhiro Suwa

Written by Suwa, Eri Yu, and Hidetoshi Nishijima

With Yu, Nishijima, and Makiko Watanabe.

The first feature of Nobuhiro Suwa, a director of TV documentaries in his mid-30s, 2/Duo (1996) is the penultimate work in the Doc Films series “Japanese Cinema After the Economic Miracle: Masaki Tamura, Cinematographer.” Having seen only one other film in the series — Shinsuke Ogawa’s remarkable two-and-a-half-hour documentary about the lives of farmers protesting the construction of Japan’s biggest airport, Narita: Heta Village (1973) — I can’t give a comprehensive account of Tamura’s work. But judging from these two very different features, I suspect I might recognize his shooting style without seeing his name in the credits. Though Narita: Heta Village is a documentary and 2/Duo a fictional narrative, the style of both displays a highly intuitive engagement with the characters, expressed most clearly in the way Tamura places and moves his camera in relation to them, neither anticipating their actions nor dogging them, but navigating the spaces they occupy with an intelligence that manages to project empathy as well as independence — a rare combination. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 31, 2001). Today (September 2, 2014), having recently reseen this movie, I’d probably give it a higher rating. — J.R.

The Curse of the Jade Scorpion

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Allen, Helen Hunt, Dan Aykroyd, Brian Markinson, Elizabeth Berkley, Charlize Theron, Wallace Shawn, and David Ogden Stiers.

I don’t want to oversell Woody Allen’s 31st feature, which I happen to like. The script is full of holes, most of the one-liners are weak and mechanical, and the plot — a nightclub magician gets two of his hypnotized subjects to steal jewels for him — is so deliberately stupid and contrived that one can probably enjoy it only by pretending it’s a routine, low-budget second feature on an old-fashioned double bill, which is obviously what Allen intended. Yet it’s possible for a picture to be not very good and still be likable — something that doesn’t happen very often for me with Allen’s pictures. (It happened, momentarily, in Everyone Says I Love You — when Allen exposed his vulnerability by singing the first 16 bars of “I’m Thru With Love.”)

The problem with most escapism nowadays is that even if it makes you forget who and where you are, it doesn’t really detach you from norms of the world you’re living in. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 10, 2004). I think I underrated The Five Obstructions, which I now regard as my probable favorite of von Trier’s films, after having reseen it, remastered, on the DVD recently released by Kino Lorber. One obvious advantage to seeing it on DVD is that Leth’s 1967 short, The Perfect Human, is included in its entirety as an extra, and even though I find it less interesting than the various “remakes” included in The Five Obstructions, finally getting a chance to see it in its entirety makes the Leth and von Trier feature a lot more satisfying and interesting. — J.R.

The Five Obstructions

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Jorgen Leth and Lars von Trier

With Leth, von Trier, Claus Nissen, Maiken Algren, Daniel Hernandez Rodriguez, Vivian Rosa, Patrick Bauchau, and Alexander Vandernoot.

What the Bleep Do We Know?

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Mark Vicente, Betsy Chasse, and William Arntz

Written by Arntz, Chasse, and Matthew Hoffman

With Marlee Matlin, Elaine Hendrix, John Ross Bowie, Robert Bailey Jr., Barry Newman, and Larry Brandenburg.

When is an “experimental film” not an experimental film? This might seem a niggling matter to the ordinary paying customer, but it’s a serious issue for artists who’ve devoted their careers and lives to experimental filmmaking, knowing that they’ve given up the possibility of a wide audience by doing so. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 5, 1999). — J.R.

This neglected feature is one of Samuel Fuller’s most energetic — his own personal favorite, in part because he financed it out of his own pocket and lost every penny (1952). It’s a giddy look at New York journalism in the 1880s that crams together a good many of Fuller’s favorite newspaper stories, legends, and conceits and places them in socko headline type. A principled cigar smoker (Gene Evans) becomes the hard-hitting editor of a new Manhattan daily, where he competes with his former employer (Mary Welch) in a grudge match full of sexual undertones; a man jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge trying to become famous; the Statue of Liberty is given to the U.S. by France, and a newspaper drive raises money for its pedestal. Enthusiasm flows into every nook and cranny of this exceptionally cozy movie; when violence breaks out in the cramped-looking set of the title street, the camera weaves in and out of the buildings as through a sports arena, in a single take. The phrase “Park Row” is repeated incessantly like a crazy mantra, and the overall fervor of this vest-pocket Citizen Kane makes journalism sound like the most exciting activity in the world, even as it turns all its practitioners into members of a Fuller-esque military squad. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1980). -– J.R.

Now that criticism and advertising are becoming harder and harder to separate in American film culture, the notion of any genuinely spontaneous movie cult becomes automatically suspect. It implies something quite counter to the megacinema of Cimino, Coppola and Spielberg — a cinema that can confidently write its own reviews (and reviewers) if it wants to, working with the foreknowledge of a guaranteed media-saturation coverage that will automatically recruit and program most of its audience, and which dictates a central part of its meaning in advance.

For a long time in the U.S. (as elsewhere), certain specialized minority interests that get shoved off the screens by the box-office bullies have been taking refuge in midnight screenings, most of them traditionally held at weekends. But what seems truly unprecedented about the elaborate cult in the U.S. that has developed around Friday and Saturday midnight screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, over the past three and a half years, is the degree to which a film has been appropriated by its youthful audience. Indeed, it might even be possible to argue that this audience, rather than allow itself to be used as an empty vessel to be filled with a filmmaker’s grand mythic meanings, has been learning how to use a film chiefly as a means of communicating with itself. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Summer 1975). I think I probably did a better job with The Godfather 33 years later, when I wrote something about it for Filmkrant. — J.R.

The Godfather Part II

‘I believe in America,’ declares an undertaker in portentous close-up at the start of The Godfather, appealing to Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) to dispatch an act of vengeance on his behalf. The sequel begins and ends with close-ups of Michael (Al Pacino), Vito’s youngest son and successor: in the first his hand is being kissed off-screen by yet another supplicant; in the last he sits alone biting his knuckle, with his wedding ring clearly in evidence — an apt symbol of his solitary dominion, with the Corleone family virtually destroyed so that its hollow emblems and relics might be preserved. The most obvious achievement of The Godfather Part II (CIC) over its predecessor can be seen in the quiet authority of this framing device, which tells us everything we need to know about the fate of the Corleones without recourse to rhetorical hectoring; its most obvious limitation is that it essentially tells us nothing new.

Perhaps more than anyone else in Hollywood, Francis Ford Coppola epitomizes the man in the middle. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 512). — J.R.

Buffalo Bill and the lndians, or

Sitting Bull’s History Lesson

U.S.A., 1976

Director : Robert Altman

Cert-A. dist-EMI. p.c–Dino De Laurentiis Corporation/Lion’s Gate Films/Talent Associates-Norton Simon. exec..-p-David Susskind. p– Robert Aitman. assoc. p–Robert Eggenweiler, Scott Bushnell, Jac Cashin. p. exec—Tommy Thompson. asst. d–Tommy Thompson,Rob Lockwood. sc–Alan Rudolph, Robert Altman. Suggested by the play Indians by Arthur Kopit. ph–Paul Lohmann. Panavision. col–Deluxe General.ed-Peter Appleton, Dennis Hill. p. designer–Tony Masters. a.d–Jack Maxsted. set dec–Dennis J. Parrish, Graham Sumner. scenic artist–Rusty Cox. sp. effects–Joe Zomar, Logan Frazee, Bill Zomar, Terry Frazee, John Thomas. M–Richard Baskin. cost–Anthony Powell. make-up–Monty Westmore. titles-Dan Perri. sd. ed–William Sawyer,_Richard Oswald. sd. rec–Jim Webb, Chris McLaughlin. sd. re-rec–Richard Portman. research–Maysie Hoy. wrangler–John Scott. l.p–Paul Newman (Buffalo Bill), Joel Grey (Nate Salsbury), Burt Lancaster (Ned Buntline). Kevin McCarthy (Major John Burke), Harvey Keitel (Ed Goodman), Allan Nicholls (Printiss Ingraham), Geraldine Chaplin (Annie Oakley). John Considine (Frank Butler), Robert Doqui (Osborne Dart), Mike Kaplan (Jules Keen), Bert Remsen (Crutch), Bonnie Leaders (Margaret), Noelle Rogers (Lucille Du Charmes), Evelyn Lear (Nina Cavalini), Denver Pyle (McLaughlin),Frank Kaquitts (Sitting Bull), Will Sampson (William Halsey), Ken Krossa (Johnny Baker), Fred N. Larsen (Buck Taylor), Jerri Duce and Joy Duce (Trick Riders), Alex Green and Gary MacKenzie (Mexican Whip and Fast Draw Act), Humphrey Gratz (Old Soldier), Pat McCormick (Grover Cleveland), Shelley Duvall (Frances Folsom). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 14, 1995). I’m not sure why, but this is one of the most popular posts on this site. — J.R.

Priest

**

Directed by Antonia Bird

Written by Jimmy McGovern

With Linus Roache, Tom Wilkinson, Cathy Tyson, Robert Carlyle, James Ellis, Lesley Sharp, Robert Pugh, and Christine Tremarco.

A friend of mine who hasn’t even seen Priest calls it “post-Oprah,” and it’s easy to see what he means — in terms of pacing as well as subject matter. Its first incarnation was as a 200-page script by Jimmy McGovern for a four-part BBC miniseries, but he shaved it to 65 pages when the BBC decided to make it a feature. When it went out to festivals last year (where it won numerous awards), director Antonia Bird’s cut was 109 minutes; since then it’s been trimmed by 8 minutes, apparently to make it eligible for an R rating: its distributor, Miramax, now under the control of the Disney studio, isn’t allowed to release any NC-17 pictures. I haven’t seen the longer version, but it’s likely that these successive abridgments have both produced the taut narrative that’s central to the movie’s powerful impact as entertainment and limited it as art and as a piece of sustained thought. Read more

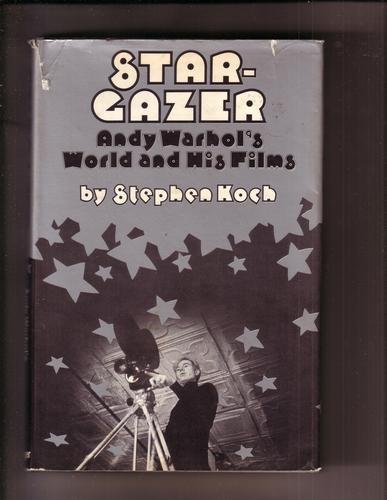

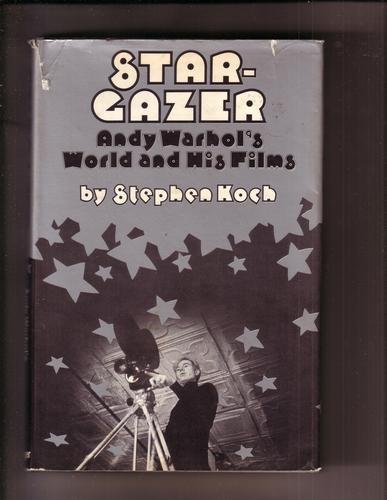

From Film Quarterly (Spring 1974). I wrote this review while I was living in Paris, which made acquiring a review copy especially difficult. (I grimly recall even getting into something resembling a fistfight with the French distributor of the book, who didn’t want to give me one and blew a fuse when I insisted, even though I had an assignment.) Stephen Koch, whom I knew from my previous stint as a graduate student at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, was a friend at the time, as was Annette Michelson, who commissioned the book for Praeger. My second-hand assessment of **** (Four Stars) came from another friend, Lorenzo Mans, who saw the entire film and reviewed it for the Village Voice, though I had attended a New York screening of Blue Movie, when it went by the title Fuck. -– J.R.

STAR-GAZER:

ANDY WARHOL’S WORLD AND HIS FILMS

BY Stephen Koch. New York: Praeger. $8.95.

Books about filmmakers that do something more than regurgitate filmographies and sketch career summaries are not exactly plentiful these days, and for this reason alone Stargazer is worthy of serious attention. What it attempts is not a mere pigeon-holing of Warhol’s films but a complex assessment of his persona and its accompanying strategies — in, through and beyond these films — as they flourished in the sixties. Read more

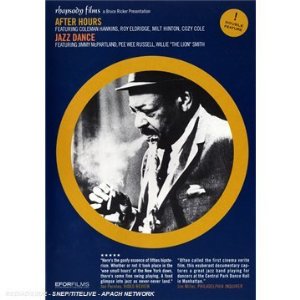

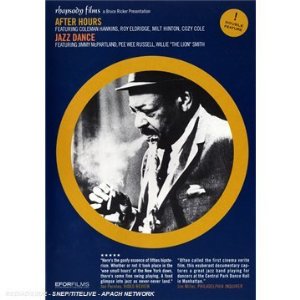

From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 510). I’ve made a couple of corrections and added several basic credits, visible now at the end of my VHS copy but not accessible to me back in 1976. (I should add that the pitches made by the coproducer to potential sponsors aren’t on the VHS version.) Thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for some help with the illustrations.–- J.R.

After Hours

U.S.A., 1961

Director: Shepard Traube

Dist–TCB. p–Shepard Traube, Arthur Small. sc–Arthur Small. p. sup– George Goodman. ph–Arthur Ornitz. ed–Morton Fallick. sd–Robert Lessner, Frank J. Gaily. m/songs—“Lover Man” by Jimmy Davis, Roger “Ram” Ramirez, Jimmy Sherman, “Sunday” by Chester Conn, Ned Miller, Bennie Krueger, Jule Styne, “Just You, Just Me” by Jesse Greer, Raymond Klages, “Taking a Chance on Love” by Vernon Duke, John Latouche, Ted Fetter, performed by Coleman Hawkins (tenor sax), Roy Eldridge (trumpet, vocals), Johnny Guarnieri (piano), Barry Galbraith (guitar), Milt Hinton (bass), Cozy Cole (drums), Carol Stevens (vocals). l.p— Meredith Gaynes (Cigarette Girl), Albert Minns (Head Waiter), Leon James (Doorman), Richard Blackmarr (Bartender). narrator— William B. Williams. 967 ft. 27 mins. (16 mm.).

A TV pilot which failed to attract sponsors, After Hours carries all the poignance of a noble lost cause. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975, Vol. 42, No. 500. — J.R.

W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings

U.S.A..1975

Director: John G. Avildsen

Cert—A. dist–Fox-Rank. p.c–20th Century-Fox. exec. p–Steve

Shagan. p–Stanley S. Canter. p. manager–William C. Davidson. asst. d

–Ric Rondell, Jerry Grandey. sc–Thomas Rickman. ph–Jim Crabe.

col–TVC; prints by DeLuxe. ed–Richard Halsey, Robbe Roberts. a.d—

Larry Paull. set dec–JimBerkey. sp. effects–Milt Rice. m–Dave Grusin.

songs–“Hound Dog” by Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, sung by Elvis

Presley; “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight” by Calvin Carter, James

Hudson; “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry; “Bye Bye Love” by

Felice Bryant, Boudleaux Bryant; “I’m Walkin’” by Antoine “Fats”

Domino, Dave Bartholomew; “Blue Suede Shoes” by Carl Lee Perkins;

“Mama Was a Convict” by Tom Rickman, Tim Mclntire; “A Friend” by

Jerry Reed; “Dirty Car Blues” (traditional), performed by Furry Lewis.

cost–Dick LaMotte. titles–PacificTitle. sd. rec–Bud Alper. sd. re-rec—

Don Bassman. stunt co-ordinator–Hal Needham. l.p–Bert Reynolds

(W.W. Read more

What an onslaught of deaths that week in late March, 2021: Morris Dickstein, Larry McMurtry, Bertrand Tavernier, George Segal….The latter prompted this reposting. From Stop Smiling No. 35 (its gambling issue, guest edited by Annie Nocenti), June 2008. — J.R.

“Trusting to luck means listening to voices,” Jean-Luc Godard reportedly said at some point in the mid-1960s. This has always struck me as being one of his more obscure aphorisms, and one that even seems to border on the mystical. Yet the minute one starts to apply it to Robert Altman’s California Split, released in 1974 —- a free-form comedy about the friendship that develops and then plays itself out between two compulsive gamblers, Charlie (Elliott Gould) and Bill (George Segal), and the first movie ever to use an eight-track mixer — it starts to make some weird kind of sense.

What’s an eight-track mixer? According to the maestro of overlapping dialogue himself, speaking in David Thompson’s Altman on Altman (Faber and Faber, 2006), this is a system known as Lion’s Gate 8-Tracks developed by Jim Webb, and it grew directly out of Altman’s ongoing efforts to make on-screen dialogue sound more real. Sound mixers would frequently complain that some actors wouldn’t speak loudly enough and Altman would counter that this was a recording problem, not a performance problem involving the actors’ deliveries. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 493). –- J.R.

Wavelength

Canada, 1967

Director: Michael Snow

Dist–London Film-makers Co–op. conceived and executed by—Michael Snow. In color. ed–Michael Snow. song—“Strawberry Fields Forever” by John Lennon, Paul McCartney. performed by—The Beatles. sd–_Michael Snow. l.p–Hollis Frampton (Man Who Dies), Amy Taubin (Woman on Phone). 1,538 ft. 45 min. (16 mm.).

A camera zooms across the length of an 80-foot urban loft, beginning from a distance approximating the camera’s fixed. Position — where most of the room is visible — and proceeding towards the four vertical double-windows, three intervening sections of wall space, desk, chairs and radiator on the opposite side, accompanied on the soundtrack by a sine wave gradually progressing from its lowest note (50 cycles per second) to its highest (12,000 cycles per second). The zoom mainly proceeds through a series of periodic jerks, between occasional shot changes, while the images pass through a variety of colored filters, film stocks, and qualities and degrees of processing (positive and negative)and light exposure (controlled by the camera, four light fixtures on the ceiling, and the time of day). It is interrupted four times by a visible human event, and during each of these the sine wave is overlaid with synchronized sound: (1) A woman and two men enter the room, and the former directs the latter to set a bookshelf down against the wall on screen left; all three leave. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin , September 1976, Vol. 43, No. 512. — J.R.

Director: Michael Snow

Canada, 1969

Dist–London Film-makers Co-op /Cinegate. conceived and executed by— Michael Snow. In colour. ed–Michael Snow. sd–Darvin Studio. with— Allan Kaprow, Emmett Williams, Max Neuhaus, Terri Marsala, Donna Aughey, Joyce Wieland, Louis Commitzer, George Murphy, Dr. Gordon, Liba Bayrak, Anne Scotty, Nancy Graves, Richard Serra, John Giorno, Paul Iden, Alison Knowles, Jud Yalkut, Susan Ay-O, Mac, students in the HEP program at Farleigh Dickinson University. 1,872 ft. 52 mins.

(16 mm.)

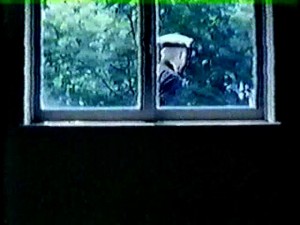

Alternative title—Back and Forth

The camera pans back and forth across an outside wall of a classroom while a man crosses part of the field. The pan resumes inside the classroom in a fixed trajectory, revealing an asymmetrical area including part of a blackboard and a door on a far wall, two pairs of windows on the wall closer to the camera, and desks in front of the blackboard; trees, building and occasionally passing vehicles are partially visible through the doors and windows.

Throughout, one hears the sound of the camera’s mechanisms, including a loud report at the beginning and end of each pan. Various cuts emphasise that certain parts of individual pans, or entire pans, or a number in series, were filmed at different times. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 22, 1994). — J.R.

** THE LION KING

(Worth seeing)

Directed by Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff

Written by Irene Mecchi, Jonathan Roberts, and Linda Woolverton

With the voices of Matthew Broderick, James Earl Jones, Jeremy Irons, Rowan Atkinson, Moira Kelly, Jim Cummings, Whoopi Goldberg, and Cheech Marin.

Though it’s somewhat less entertaining than The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin, The Lion King marks a welcome and fascinating shift in the Disney animated feature. It may be just a coincidence, but Disney’s new live-action Angels in the Outfield, a multicultural remake of a 1951 baseball fantasy, marks the same kind of racial and ethnic reorientation. I’d like to think that the widespread (and justifiable) objections raised by Middle Eastern groups to the xenophobic stereotypes in Aladdin have finally led to some rethinking by Disney executives about how to handle such ethnic material. If my hunch is correct, these changes represent not so much a kowtowing to political correctness as a more accurate reckoning of Disney’s stateside and international audience.

The issue isn’t exactly reality versus fantasy, because all Disney pictures are fantasies. In real life a white orphan isn’t likely to be adopted by a black man even if the white orphan’s best friend is a black orphan who comes along with the bargain (as in Angels in the Outfield). Read more