From Sight and Sound (Spring 1983). -– J.R.

Wayne Wang: Chinese structures and American economies

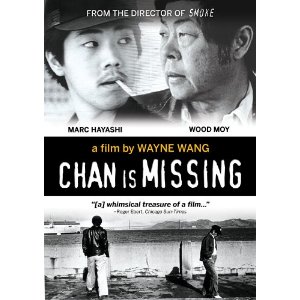

Opening with a rousing Cantonese version of ‘Rock Around the Clock’ which is all about inflation — the rising cost of tea and rice — Wayne Wang’s remarkable, offbeat Chan is Missing neatly combines its concern about what it means to be Chinese-American with the current economic crisis. Praised in these pages by Richard Combs after its appearance at the 1982 London festival as a film that ‘answers nothing, but in a way satisfies one’s curiosity,’ this black and white mystery, about two Oriental cab drivers searching for their missing partner through San Francisco’s Chinatown, has done surprisingly well since its U.S. release last fall, especially for an independent feature costing under $20,000. A strong review from the New York Times‘ Vincent Canby, coupled with careful handling by New Yorker Films, helped to turn the film into something of a commercial sleeper. ‘After the first quarterly report, we were already in the black,’ Wang cheerfully told me on the phone from San Francisco early this year, adding that the cast and crew members, who had originally been partially paid off in points, were already just starting to get proceeds for work done in 1980. The film was shot over ten consecutive weekends that summer. ‘The script took a lot of turns,’ Wang recalled last spring in New York. ‘Originally it was something else that involved a black taxi driver and the whole black community was somewhat involved. And then I dropped out because I didn’t feel I really had a grip on it. Then it got real structural; I showed that script to the cast and crew, and they had problems with it. So I started changing the script into something that was more narrative and more linear. That went on for about a year.

‘Actually, that very structural, theoretical idea interested me a lot. I was fascinated by the evolution of the Chinese written word. It has six stages, but I took the four main ones — which, incidentally, also influenced Eisenstein’s theory of montage. The first stage is what is called the image: you draw a stylized picture of what you want to express, such as a knife. The second stage is called painting to the situation, so let’s say you want simply to deal with the point of the knife: you can’t draw that by itself, so you draw a knife with a slash where the point is. The third stage is what’s called the meeting of ideas, when you take two different pictures and put them together, like a knife and a heart. If you have a knife in your heart, you need patience, so the concept of patience comes out of that. And the fourth stage is the relationship between picture and sound, where you take the sound of one character and the picture of another character.

‘So the original idea was to base the whole mystery on that structure and evolution. But since this was obviously going to be the first major Chinese-American film done in this country, it seemed a little selfish for me to do this structural film rather than something that’s more accessible to more people. At the same time I don’t want to give up some of the things I really want to do with films. So that’s why the ending of Chan is Missing moves from something very specific to something that’s much more structural and abstract, where there are literally flash frames in the water shots . . .’

Wang is also interested in exploring the ways that the structure of Chinese painting might apply to cinema, ‘for example, shooting from a higher-up perspective, using wide shots more.’ A native of Hong Kong and former art student who has spent nearly half his life in the U.S., he started out about a decade ago with a low-budget American feature made with two friends, Rick Schmidt and Richard R. Richardson, A Man, a Woman and a Killer. After several shorts, some TV work in both Hong Kong and the U.S., and some community work in San Francisco, he made a 45-minute film on an animation table using stills, New Relationships, that was also about Chinatown. ‘Very much a Godardian, analytical film about images of the Chinese,’ he says. Chan Is Missing finally took shape after Wang received a $10,000 A.F.I. production grant on the basis of a script.

Since the success of Chan, Wang has been busy preparing two separate murder mysteries, both in 35mm and color, which he intends to shoot in swift succession this spring. Who You Know, a low-budget studio project to be shot in Venice, California, is first on his agenda, based on a script by Henry Bean. ‘It’s basically about a man who is afraid of his own imagination, and also afraid that he has a tendency to violence against women in a relationship. He’s a reporter, and he starts writing about this sex murder, and discovers that he’s incriminating himself.’

Wang’s second project is Illegal, ‘a thriller that deals with an illegal immigrant and redevelopment in Chinatown,’ to be made in San Francisco by his own recently formed C.I.M. Productions, named after the initial letters of Chan Is Missing, Once again he will be working with a mainly Asian cast, with actors from China and Hong Kong as well as local talent. He seems understandably eager to stick to the principles of economy which generated Chan is Missing, including the principle of absence Pointed to in the title — the Yin-and-Yang notion whereby what’s missing from the screen is just as important as what’s there. From this point of view, it would seem that most of Wang’s past and present projects adopt the frugal policy of starting with something that already exists. In the case of Chan, this is the popular image of the Chinese in American culture as epitomized by Charlie Chan. What this will be (and mean) in Who You Know and Illegal is open to some conjecture, but the titles already provide telling clues.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM