The following essay was both commissioned and written in early June 2009. My thanks to the Chinese translator Zhanxiong Xu for giving me permission to publish the original English version here.

I’m also pleased to announce that a Chinese translation and edition of one of my own books, Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, came out in China. I strongly suspect that the subsequent influx of Chinese visitors to this site must have had something to do with its publication. — J.R.

Introduction to the Chinese Edition of More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

I

“The Chinese don’t accord much importance to things of the past,” Maggie Cheung maintained in an interview with a French magazine roughly a decade ago (1), “whether it’s films, heritage, or even clothes or furniture. In Asia nothing is preserved, turning towards the past is regarded as stupid, aberrant.”

Interestingly, this statement helps to explain why so many of the most important Chinese films, at least for me, are concerned with the discovery of history, and represent various attempts to reclaim a lost past. I’ll restrict myself to a short list of a dozen favorite Chinese features, all of which exhibit these traits: Fei Mu’s Xiao cheng zhi chun (Spring in a Small Town, 1948); Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Bei qing cheng shi (City of Sadness, 1989) and Xi meng ren sheng (The Puppetmaster, 1993); Wong Kar-wai’s A Fei zheng chuan (Days of Being Wild, 1990) and Fa yeung nin wa (In the Mood for Love, 2000); Edward Yang’s Gu ling jie shao nian sha ren shi jian (A Brighter Summer Day, 1991); Stanley Kwan’s Ruan Lingyu (1992); Tian Zhuangzhuang’s Lan feng zheng (The Blue Kite, 1993); Li Shaohong’s Hong fen (Blush, 1994); and Jia Zhangke’s Zhantai (Platform, 2000), Sanxia Haoren (Still Life, 2006), and Er shi si cheng ji (24 City, 2008). As I once described Ruan Lingyu in the title of a 2001 essay, this is a bit like “Building History in Quicksand”. And even many of my other favorite Chinese films that are stuck in the present, and view this present in all its modernity, such as Hou’s Nan guo zai jan, nan guo (Goodbye South, Goodbye, 1996), Peter Chen’s Tian mi mi (Comrades: Almost a Love Story, 1996), and Jia’s Shijie (The World, 2004), might be described as ambitious efforts to view the present historically.

Cheung’s statement also describes the biases of many Americans, although it’s somewhat less true of the portion of the United States where James Naremore and I both grew up, the South. Ever since losing the Civil War (1861-1865) — the most traumatic cultural crisis our country has suffered to date (in part because it put an end to slavery), depicted in two of the most famous American films, The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone With the Wind (1939) — Southerners have often had a somewhat wistful nostalgia about a mythical Golden Age that supposedly existed before that war. But one could also argue that cherishing an imaginary past is yet another way of devaluing history. It’s also a valuable capitalist tool that allows certain products to be sold and resold, especially in a present that both yearns for history and deeply mistrusts it.

Film noir has a complicated and ambiguous relation to the past reflecting this ambivalence, and Naremore is, to the best of my knowledge, the critic and historian who has done by far the best job in describing this phenomenon and helping us to understand it. In a way, he starts from the paradox that virtually anyone who enters a video store in the United States today knows what “film noir” is, yet the original American audiences for the Hollywood classics in this branch of filmmaking, all made during the 1940s and 50s, wouldn’t have heard or known this term. Consequently, one could argue that, in certain respects, a taste for film noir today respects a kind of nostalgia for a past that never existed—or at least one that didn’t exist in the terms by which we currently know that past.

II

Jim Naremore has been a good friend for over two decades, and I suspect that one thing that has made our tastes and interests so compatible is a tendency to view film at least partially as a branch of literature — a reflection of our academic backgrounds and our reading habits. I consider this background relevant to what makes More Than Night the best book about film noir, because, as Naremore himself shows in some detail in his first chapter, even the term “noir” has literary connotations: It was a term partly inspired as well as paralleled by the French publisher Gallimard’s Série noire — a series of black-jacketed paperback crime novels inaugurated in 1945 by an editor with a background in Surrealism, Marcel Duhamel (and, according to the French edition of the online encyclopedia Wikipedia, a series named by an even more celebrated French Surrealist, writer Jacques Prévert — who scripted the famous film Les enfants du paradis the same year). Even though French writers in the late 1930s had already employed the term “film noir” in reference to such atmospheric French films as Pépé le Moko (1936), Hôtel du Nord (1938), and Le jour se lève (1939), it entered common usage thanks to a book series that specialized in French translations of such American authors as Raymond Chandler, David Goodis, Dashiell Hammett, Ed McBain, Horace McCoy, and Jim Thompson, many of whose works had been (or later would be) adapted into films. (To complicate this lineage, according to Wikipedia, Duhamel also started another book series at Gallimard in 1949 called Série blême — literally, “pale series,” with green instead of black jackets — devoted to suspense novels; their first title was a French translation of I Married a Dead Man, by William Irish, a pseudonym for Cornell Woolrich, the same writer who wrote the original stories for many famous noir films, such as The Leopard Man, Phantom Lady, and The Window, as well as the Alfred Hitchcock thriller Rear Window.)

It’s important to add that the association of film with literature, as in the case of noir, is largely a French tradition that came to fruition with the Nouvelle Vague — most obviously in such films as Jean-Luc Godard’s À Bout de Souffle (1960) and Alphaville (1965, where film noir gets cross-bred with science fiction) and François Truffaut’s Tirez sur le Pianiste (1960, based on a novel by David Goodis) and La mariée était en noir (1968, based on a novel by William Irish). Over three decades later, Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville’s 2 X 50 ans du cinéma français (1995) ends with a moving tribute to French film criticism — using that term broadly enough to include precursors as well as poets, art critics, and filmmaker-theorists — by offering a honor roll of 15 individuals, from Denis Diderot (1713-1784) to Serge Daney (1944-1992), each of whom is accorded a portrait, a page of text, and an offscreen recitation of a brief passage read aloud by either Miéville or Godard. And the same orientation is evident in the film magazine that Daney founded shortly before his death, Trafic, which Jim and I have both contributed to. (Jim’s contribution, appropriately, was about the classic noir Double Indemnity, also discussed in depth in More Than Night.)

Naremore’s background in literature plays more than an incidental role in his writing. His very first book, The World Without a Self: Virginia Woolf and the Novel (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1973), is about one of the key figures in early 20th century English modernist fiction. And among the special virtues of his subsequent book The Magic World of Orson Welles (New York/London: Oxford University Press, 1978; 2nd edition, Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1989) — making it, for me, the best critical study of Welles in any language — is its unusual sensitivity to literary as well as political issues in Welles’ career, both of which have tended to receive superficial treatment in most of the other books about him. A similar case could be made on behalf of Naremore’s most recent book, On Kubrick (London: British Film Institute, 2007), which I similarly regard as the best critical study of Stanley Kubrick, although in this case the mastery that Naremore brings to his subject isn’t just a matter of literature (evident in his comprehensive treatments of Kubrick’s literary sources) but also a matter of art history (in both his precise account of Kubrick’s early career as a photojournalist and his broader treatment of “grotesque” aesthetics, which actually combines visual and literary analysis).

More generally, one of the unusual strengths Naremore has as a critic and historian — no less evident in his groundbreaking Acting in the Cinema (Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988), his short book The Films of Vincente Minnelli (Cambridge University Press, 1993), and the study guides he has written or edited devoted to Psycho, North by Northwest, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Citizen Kane, and film adaptation (not to mention a good many superb essays that have not yet been collected) — is the literary distinction and grace of his prose, which makes him stand apart from his more jargon-ridden academic colleagues.

III

French appreciation of American culture, including literature and film, has had a decisive effect on the appreciation of Americans — including Naremore and myself — for their own culture. This is certainly true in my case, because a major part of my film education was conducted during between 1968 and 1974, when I was living in Paris, and had direct access to many of the greatest American films of the past, westerns and noirs in particular, that were less readily available in the United States, especially in commercial cinemas. (Jim has lived in Europe as well, albeit in Germany rather than France.) It’s significant that writers as important as Edgar Allen Poe and William Faulkner were taken seriously in France long before they were in their own country, and the same is largely true of such American-based directors as Samuel Fuller, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, Frank Tashlin, and Orson Welles, all of whom have been associated with noir at one time or another.

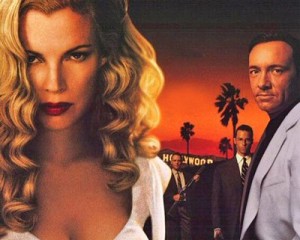

Just as the present-day American taste for noir tends to combine a nostalgic view of the past with a reluctance to view that past historically, there is a similar ambivalence regarding the relation of film noir to political and social criticism. One of the most valuable aspects of Naremore’s criticism is the degree to which it’s inflected by a leftist critique of American culture. This means, on the one hand, that’s he unusually attentive to films that criticize American culture from a political perspective, such as Try and Get Me (1950) and The Glass Shield (1995), and, on the other hand, he’s uncharacteristically critical from a leftist perspective of some of the most popular neo-noir films, including Chinatown (1974) and L.A. Confidential (1997), in contrast to most other American critics, who tend to accept their defeatist politics without challenge.

Naremore also takes the unusual step of considering experimental films that utilize the imagery and themes of film noir, such as Mark Rappaport’s 36-minute Exterior Night (1994) — one of the many titles analyzed in detail here that isn’t available commercially. It’s an unfortunate habit of many American film critics, in academia and journalism alike, to reflect passively the whims and omissions of mainstream distributors by either consciously or unconsciously canonizing the few films lucky enough to receive millions of dollars in publicity while frequently ignoring most or all of the others. Like all of the best film critics, Naremore has a view of both culture in general and cinema in particular that’s much wider than the marketplace. For the past two years, he has been writing lengthy articles for the magazine Film Quarterly devoted to his ten favorite films of the previous year — an unusual step to take for an academic film writer who lives in a small town, even a retired one who spends part of every year in Chicago. (For the remainder of every year, he lives in Bloomington, Indiana, where he used to teach.) But nowadays, with the wide circulation of DVDs, it’s no longer necessary to live in New York or Paris or Tokyo or Beijing in order to keep up with the major currents of film history from an artistic as well as commercial standpoint. And it’s worth adding that his favorite film in 2008 was 24 City.

__________________________________________________________________

1. Les inrockuptibles, December 1, 1999.