From the Chicago Reader (March 20, 1992). — J.R.

MR. COCONUT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Clifton Ko

Written by Ko, Michael Hui, and Raymond Wong

With Hui, Wong, Olivia Cheng, Ricky Hui, Maria Cordero, and Joi Wong.

KING OF CHESS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Yim Ho and Tsui Hark

Written by Yim and Tony Leung

With Leung, John Sham, Yong Lin, Yia Ho, King Shin Chien, and Chan Koon Cheung.

![Mr. Coconut[DVDRip] 450c5e100a576972b5dc85c0a24988d7 Mr. Coconut[DVDRip]](http://img.emuleday.com/data/img/45/450c5e100a576972b5dc85c0a24988d7.jpg)

Past, present or future . . . China will always belong to the Chinese people. — opening title in King of Chess

In this country there is probably no important national cinema more neglected than the Chinese — actually a transnational entity, as I’m defining it here, including movies from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. And probably no programmer in this country is more dedicated to making Chinese cinema known than Barbara Scharres, director of the Film Center.

I have to admit to a certain resistance to Chinese cinema in the past, and to Hong Kong movies in particular. It’s a bias shared by many of my colleagues, for reasons that are in part self-serving: if we were to suddenly acknowledge the importance of Hong Kong movies, we’d be forced to acknowledge many years of negligence on our part, and obliged to admit an embarrassing lack of knowledge and sophistication on the subject. (Similarly, the New Yorker‘s refusal to accord even a capsule review to La belle noiseuse can, I suspect, be explained by its long history of neglecting Jacques Rivette, and the same thing goes for its silence on Andrei Tarkovsky.)

According to Chiao Hsiung-Ping, a Taiwanese critic, “the only special qualities of Hong Kong cinema are precisely entertainment and commerce,” the two qualities she finds most lacking in the cinema of Taiwan. “Hong Kong cinema belongs to a young audience, and its creativity tends towards the high spirits and unrestrained fantasies of the young. In this system, stars are a box office guarantee that is still required. . . . Because they are young, the Hong Kong audience is especially attracted by speed, novelty, and fantasy. If one can say Taiwanese films are the products of reflection and nostalgia by intellectuals in their 30s and 40s, then Hong Kong films represent the dynamism of people in their early 20s.”

For me, this is both the advantage and the drawback of Hong Kong cinema; certainly that dynamism has a lot to do with the ways that it’s been celebrated by a handful of Anglo-American critics. The fact that it’s truly a popular cinema made for a regular-attendance audience — the kind of cinema we used to have in the United States before the old studio system fell apart and event-oriented attendance and video rentals took over — seems to make it, for many English and American enthusiasts, a return to childhood innocence and a certain antiintellectual simplicity. Scharres’s current Hong Kong series at the Film Center, like her other efforts to make Chinese movies better known here, is considerably more comprehensive than this description implies. But the delirious title of her series — “Incredibly Hong Kong!,” which sounds like it could have been dreamed up by Bill and Ted — still points in this general direction, and something in me resists this sort of appeal.

When Tsui Hark was first recommended to me as the Chinese Spielberg (around the time of his Peking Opera Blues), that was enough in itself to cool my interest. Subsequent looks at his highly skilled work, which seemed to confirm this comparison, were further turnoffs, especially since in my opinion world cinema already has at least one Steven Spielberg too many. I was also less than enthralled by John Woo’s A Bullet in the Head, praised to the skies by many critics I respect, because American movies already inundate us with baroque exercises in extreme violence and dumb-ass male prerogatives. (Hong Kong critic Stephen Teo has suggested, in “The Legacy of T.E. Lawrence: The Forward Policy of Western Film Critics in the Far East,” that the spectacle of Western critics enthusing over John Woo movies would be roughly comparable to Asian experts on Anglo-American cinema flipping over Michael Winner’s Death Wish movies.)

Of the small sampling of Hong Kong films I’ve seen, the ones I’ve liked best are not usually the pop action blockbusters but some of the so-called art movies, which in some cases have been box-office failures (largely because there is no art-movie market in Hong Kong): Yim Ho’s Homecoming (1984), Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild (1990), Stanley Kwan’s Actress/Center Stage (1991), and Yim Ho and Tsui Hark’s King of Chess (1991). The more popular ones that interest me are usually the ones that have the most to tell about Chinese culture — and these are not always the best from other points of view.

Fans of the popular comic star and auteur Michael Hui — whose movies form the centerpiece of “Incredibly Hong Kong!” — tend to prefer the films he directed himself, especially The Private Eyes and Security Unlimited, to the ones he merely produced, cowrote, or starred in. Since I previewed these movies without subtitles I’m not qualified to judge them (and I certainly can’t comment on what they might have to tell us about Chinese culture). I found much more to enjoy and think about in Chicken and Duck Talk and Mr. Coconut, star vehicles for Hui directed by Clifton Ko, which I was able to see with subtitles.

King of Chess and Mr. Coconut are especially interesting to me because they deal with the very topical subject of the relation of Hong Kong to mainland China (the “absorption” of Hong Kong into the mainland being scheduled for 1997). Each movie dramatizes in a very different way the social, moral, and aesthetic tensions between the two cultures, and neither seeks to make this conflict into a simple one, with right on one side and wrong on the other; in fact both seek a soulful bonding between the best of what is Chinese in both cultures.

The five Hui comedies I’ve seen so far all contain the following elements, whether or not he is directing: a central and somewhat obnoxious character played by Hui himself; sudden periodic bursts of rapid and highly rhythmic action, often accompanied by familiar patches of Western music; gags involving food; an emphasis on the changes in architecture, technology, and life-styles in contemporary Hong Kong; elaborate and/or extended dream sequences involving extravagant wish fulfillment; and at least a few moments of homey, salt-of-the-earth sentimentality.

Mr. Coconut begins with the collision of two small boats on a river in southern China. The title hero (Hui), picking coconuts at the time, swings down on a rope, Tarzan-style, to rescue drowning passengers while the boats’ owners are onshore fighting over their financial losses. A crude but good-natured member of a village commune, Mr. Coconut is next seen casually defeating a big man who threatens him with a big stick (the hero has an even bigger stick) after a comic display of macho bluster. Then he chastises some boys for watching him fish rather than attending school (“Do you want to be like me when you grow up?”), and finally he puts out his cigarette on the ground with a well-aimed gob of spit.

While he’s distributing some of his fishes to the boys and to other villagers Mr. Coconut receives a letter from his sister Ping (Olivia Cheng) in Hong Kong. He hasn’t seen her in over 20 years, since she left the village at age eight, and she proposes that he come for a visit. As he speaks to another member of the commune about Ping’s husband Kar-fan (Raymond Wong), who manages a Hong Kong shoe store and helps to finance the commune school, a fast-motion comic montage of Hong Kong street life leads into shots of Kar-fan at work, attending to a fussy customer. Kar-fan’s hefty, dictatorial female boss (Maria Cordero) turns up — introduced in a comic low angle that emphasizes her bulk — and proceeds to chew him out. Then, while Kar-fan is taking the subway home, he is confused with a flasher ogling a young woman, and a friend (Ricky Hui, Michael’s brother) who rescues him from this predicament proceeds to try to sell him a vacuum cleaner.

Even this brief summary shows how mainland and Hong Kong life-styles are contrasted from the start. These contrasts come to a head the moment Mr. Coconut moves into Kar-fan’s small and already crowded flat in a government resettlement high rise, where Kar-fan lives with his wife, his sister Ling (Joi Wong), and two daughters. Here Hui’s playing of the A Can role — that of the mainland hick visiting Hong Kong, a comic stereotype in Cantonese cinema since the 50s — virtually inverts his usual comic persona, a mixture of urban greed, hypocrisy, and cowardice that here is more or less taken over by the character of Kar-fan. (Significantly, the movie’s first dream sequence belongs to him rather than to Mr. Coconut — Kar-fan concocts an elaborate fantasy, based on the news that his sister is dating a wealthy young man, in which he cashes in on a marriage between the two.)

Mr. Coconut disrupts the family largely through his spitting, his smoking, and his eating habits. (He prefers a portable spittoon to the toilet, is the only smoker in the household, and pigs out at every meal.) Significantly, it’s mainly his brother-in-law, the bourgeois butt of most of the gags, who is driven up the wall by these and other personal habits; the other family members tend to be more tolerant.

The varying degrees of vulgarity, ingenuity, grace, and strain involved in these gags make for some uneven mixtures. The hero’s comic monologue about the usefulness of spittoons at government summit meetings and his schemes for containing cigarette smoke (such as blowing it into plastic bags that he seals and then collects in piles) are genuinely funny. But I was less amused by the countless gags about Kar-fan’s boss, based on her girth, overall unattractiveness, and battle-ax meanness. Many of these gags are contained in the longest and oddest Hui dream sequence I’ve seen, which occurs after Kar-fan tries to get the hero hired at the shoe store and Mr. Coconut flirts with the boss, thereby tickling her vanity. In the dream he gets invited to her house for a romantic rendezvous by her swimming pool (which needless to say ushers in a Jaws gag). The strangest thing about this dream is that it’s impossible to tell precisely when it begins and which character is having the fantasy.

Mr. Coconut is less episodic than the other Hui comedies I’ve seen, but some of the plot developments seem contrived rather than logical outgrowths of the material. The hero wins a round-trip flight to London on a TV game show, for instance, and gets waylaid in Africa en route; his family believes he’s dead, but even after he turns up alive Kar-fan tries to collect life insurance on him, and many of the movie’s later sections are devoted to complications arising from that scam. Eventually, of course, the hero winds up the apple of everyone’s eye rather than an embarrassment, and it’s implied that his yuppie brother-in-law is morally improved by his contact with him.

One reason it’s hard to find much critical guidance about Hong Kong movies is that most of what’s written about them in English comes from within the Hong Kong film industry, which monotonously emphasizes box-office grosses over everything else, and is in a form of English that borders on gibberish. (Comparable gibberish turns up in the subtitles of many Hong Kong films.) Programmers’ capsule descriptions tend to be more promotional than critical, and the same is often true of the few reviews by Anglo-American critics, some of whom have industry links. Of course there’s a thin line everywhere between most film criticism and publicity, but Hong Kong hype and jive is unusually intense.

So it’s not surprising that though most capsule descriptions of King of Chess say that it intercuts between two stories and has two directors — Yim Ho and Tsui Hark — none that I’ve seen explains that the use of two directors was not part of the original design. (The stories are based on two novels by two authors, Cheung Hay Kwok and Chung Ah Shing — the first is set in present-day Taipei, the second in a mainland China labor camp during the Cultural Revolution.)

It turns out that Yim Ho — the gifted director of Homecoming (1984), which I reviewed favorably when it showed at Facets Multimedia in late 1987 — started shooting King of Chess in Taipei around that time, from a script that he wrote with Tony Leung, one of his lead actors. But the following year Yim either quit the film or was fired, apparently due to its escalating budget. Tsui Hark, the producer, eventually took over as director, recasting the female lead, and the film was finally released four years after it began shooting, in a version disowned by Yim (though the film credits list him as the only director). Hou Hsiao-hsien, probably the greatest of all Taiwanese filmmakers, served as associate producer.

Considering the extreme stylistic disparity between other films by Yim and Tsui — the quiet insights and compositional densities of Homecoming, the frantic action choreography and tart humor of Once Upon a Time in China — it’s hard to imagine their visions coexisting on any terms at all, yet the finished film is surprisingly cohesive. It appears that the mainland sections were all directed by Yim and the Taipei sections were all — or mainly — directed by Tsui, who was also in charge of the final editing; but perhaps because the film’s structure is predicated on strong contrasts, the two stories wind up supporting one another. As with the alternating and contrapuntal plots in Faulkner’s The Wild Palms, the stories’ parallel developments are not necessarily any more important than their differences. The Taipei story is as critical of capitalism as the mainland story is of lMaoist communism, yet the plot of each hinges on the exploitation of a chess master.

The movie begins and ends with newsreel footage of mass demonstrations in 1967 in response to Mao’s Cultural Revolution, accompanied by a Hong Kong rock song whose lyrics are worth quoting: “I think of you every time I close my eyes. / You’re like an alluring slogan that won’t leave. / In a world of deceit and betrayal / We have to learn to protect ourselves. / My beloved comrade, let me believe in your loyalty. / Perhaps I am not a perfect example of love. / I cannot distinguish the left from the right. / It’s an unknown force which compels us / To lose our way or find ourselves. / Comrade, my love, let me embrace you.”

After this song we’re plunged into the high-tech world of contemporary Taipei, where a young TV hostess named Jade (Yong Lin) is about to be dumped from her show, Whiz Kids World, because of a drop in ratings. She enlists the help of Ching (John Sham), a friend in advertising from Hong Kong, and as they look through a list of prospective whiz kids for the show Ching’s interest is sparked by a young chess prodigy. On his way to meet with the boy he recalls another, older chess master named Wong (played by cowriter Tony Leung) he met on the mainland while visiting a cousin in the 60s, and this leads directly into the second story.

After Ching finds the whiz kid — a street waif with psychic powers — in a Taipei temple, he concocts a scheme for rigging a series of chess games between the boy and Professor Lau, a computer tycoon. This leads to some brittle satire about the heartlessness and cynicism of Taiwanese capitalism: Jade winds up sleeping with Lau to secure his participation on the show as both chess player and sponsor, and Ching’s friends on the stock market exploit the boy’s psychic powers. To make matters worse, Lau eventually kidnaps the boy, and when Ching tries to retrieve him there’s an accident that causes the boy to lose his psychic powers.

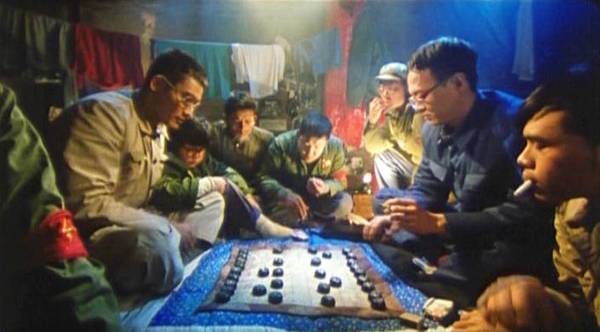

The parallel story of Wong at the farm commune offers an equally jaundiced view of life, but here it’s under Maoist communism. The style of these sections is much more reflective and lyrical, but the overall message is no less satirical — the poor chess master in this case is just as much a victim of other people’s agendas. During a Red Guard purge, an antique ebony chess set inherited by Ching’s cousin becomes a symbol of decadence, until Wong helps the cousin out by claiming it as his own. Then, because Wong’s background is so impoverished, it becomes a “glorification of the revolutionary spirit of a classless society.” Soon afterward, however, Wong’s mastery is dismissed as irrelevant by an officer who assigns him to play basketball instead of chess because he’s so tall.

Ching first encounters Wong next to the toilet on a train bound for the commune, and thanks to another toilet Wong later gets into serious trouble: neglecting to bring toilet paper to an outhouse, he innocently tears off part of a banner bearing Maoist slogans as a handy replacement, which lands him in prison as a counterrevolutionary. Ching’s cousin then uses the antique chess set to bail Wong out of prison, just in time to play in a tournament — a competition that could earn Wong a job transfer if he wins.

The Taipei story also builds to a climactic chess game, but the points of both stories aren’t found so much in the games or their outcomes as they are in the words of the Hong Kong rock song. Significantly, the second time we hear this song, what we see are shots of Taipei as well as mainland China: “In a world of deceit and betrayal we have to learn to protect ourselves. . . . I cannot distinguish the left from the right. It’s an unknown force which compels us to lose our way or find ourselves. Comrade, my love, let me embrace you…”