From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 2003), where it was printed under the title “Against the Tide”. — J.R.

While putting together a collection of my film pieces for an upcoming book I included an appendix listing my 1,000 favorite films and videos made between 1895 and the present — features and shorts, live action and animation, narrative and experimental. The point was to cite not the works I consider the most important historically but the ones that still provide me with the most pleasure and edification.

This took more work than anticipated because I didn’t have a surefire method of recalling all the possible candidates. I worried about the inevitable oversights, including even ones from 2002. I also worried that I’d wind up weighting the list with more old than recent films — a fear that proved to be mainly groundless. The year between 1924 and 2002 for which I listed the fewest titles — five — was 1937. Four other years — 1926, 1939, 1942, and 1945 — yielded only six apiece. The peak year was 1955, with 21 titles. Generally speaking, there was a steady rise through the 50s, a decline in the 60s, then a leveling off: 17 items in the teens, 72 in the 20s, 95 in the 30s, 103 in the 40s, 160 in the 50s, 133 in the 60s, 130 in the 70s, 129 in the 80s, and 125 in the 90s.

Obviously my list was slightly skewed: I grew up in the 50s and saw more films then than in any other decade, and I’ve had relatively few occasions to see those made in previous decades. But the received wisdom that movies as an art form peaked in the 60s and 70s and then tapered off drastically — which appears to be the central premise of all the editions of David Thomson’s much praised Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema — isn’t supported by my list, which shows only a slight decline between 1960 and the present.

Does this make me a sucker for contemporary movies? According to the cinema-is-dead people, it must. But I would argue that when most old fogies get ecstatic about films seen in their youth, they’re really getting ecstatic mostly about their youth, and the films they saw then gain in stature by association. The 60s and 70s were so great because those were the decades when people finally felt licensed to take films seriously. Before and after, at least in this country, business dominated the discourse to such an extent that people who took films seriously were often made to feel delusional. The motto of this discourse is, Hey, it’s only a movie. To which I’m often tempted to reply, Hey, it’s not just a business.

Of course, it’s also a truism that the closer you get to the present, the likelier it is that a favorite will eventually be forgotten. This is no doubt what literary critic Harold Bloom had in mind when he implied that it’s the sifting out of time and history, not critics, that establishes a canon. Yet I believe that the business and the critical discourse combine to do much of the sifting — by making cultural items available or unavailable, valued or devalued. If I had to name all the possible contenders for the best films of 1920 in 2002, the list I’d come up with would have at least as much to say about 2002 as it would about 1920. By the same token, choosing the best movies of 2002 in 2002 entails making wild guesses about what selections might survive until 2084.

As it happens, only four of the movies on my 2002 ten-best list showed in commercial theaters in Chicago this year; and three others — including my top two — showed so briefly in art venues you probably missed them. The same is true of my list of runners-up — which suggests that it isn’t the public so much as it is the systems of dissemination and promotion that determine most of what we wind up seeing. I assume that some of my readers who complain that I don’t seem to like movies are defining “movies” according to the extremely limited selection given high-profile sales pitches — which is a bit like defining good literature by what you can pick up at Wal-Mart. Unfortunately the cinema-is-dead “experts” tend to be swayed by the same pitches.

It doesn’t help that Hollywood has an advanced case of remake-and-sequel syndrome, a form of exhausted reflex thinking about what pays off (with a parallel in the current extensive security checks at airports, which stem from the curious assumption that future terrorist attacks will involve planes simply because they did before). I confess to sometimes being guilty of a similar kind of reflexive thinking, defining new movies in relation to tried-and-true classics, but I hasten to add that few of my first and second choices for a ten-best slate have anything to do with remakes or sequels. In this respect, I feel I’m voting against those cultural planners who assume that we want or deserve only some refurbished version of what we already know.

1. *Corpus Callosum. I’ve seen Michael Snow’s sprightly experimental feature from Canada, which showed at a couple of weekend matinees at Facets early last October, three times in various theaters and many times on video, and I’ve found it virtually inexhaustible — each viewing has felt like a brand-new encounter rather than the replay of a golden oldie. Not all of my colleagues who’ve seen this magnum opus would agree that it’s the crowning achievement of North America’s greatest living experimental filmmaker and conceptual artist, but I’m far from alone in my estimation of this masterpiece.

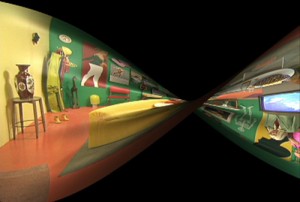

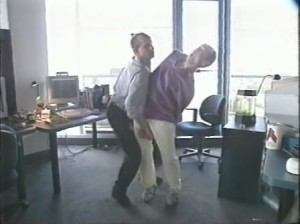

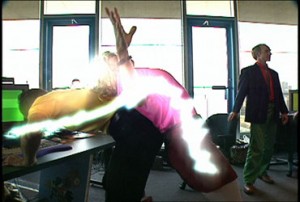

It’s a kind of playful and comic encyclopedia of all the things digital video can do to stretch, compress, combine, and otherwise distort human bodies, compiled with neither malice nor anxiety. It unravels mainly in two contrasting spaces. One is a circular work space spotted with people at computers and backed by picture windows overlooking skyscrapers, which the camera glides past in perpetual motion. The other, viewed from a fixed vantage point, is a windowless boxlike chamber resembling both a living room and a bomb shelter, where kitschy objects and members of a nuclear family clustered around a TV set appear, disappear, explode, reappear, and get scrambled in various combinations.

Snow’s first digital video was in gestation for many years while he waited for the necessary technology to develop, and since he started out as an animator (he concludes *Corpus Callosum with his very first piece of animation), he knows that this kind of patience can sometimes pay off in unexpected ways. I’ve argued elsewhere that the long-range working methods of animators may allow them, quite apart from their conscious intentions, to bear witness to their time in certain respects more profoundly than live-action filmmakers, who work within much shorter time frames. Furthermore, the endless possibilities of digital video, which allow conceptual artists to achieve precisely what they think, are a boon to someone as focused as Snow, though they’ve handicapped many less imaginative and original filmmakers by making their work too easy.

The film’s title refers to the tissue that passes messages between the brain’s two hemispheres. The asterisk, as Snow has noted, means what an asterisk generally means — a sign pointing toward an extension of the material. Its addition clearly baffled some; when I reviewed the film for Film Comment the asterisk got shaved off as if it were a wart, and the error wasn’t deemed important enough to warrant correcting. Yet the asterisk points to what I value most about the film, which goes beyond the kind of formalism usually associated with Snow to meditate on the ways human bodies have occupied interior spaces over the past half century. On this very broad canvas, rhymes of shape, costume, decor, movement, and viewing itself (with functional work-space computers supplanting kitschy living-space TVs) are combined with contrasting ideas about how space is represented and negotiated. All of which yields a kaleidoscopic vaudeville that recapitulates and updates most of the concerns of Snow’s earlier work — including camera movement, working and living space, philosophical journeys, and mathematical paradoxes such as the Moebius strip — while teasing out some of their social implications.

2. Platform. I’ve seen Jia Zhang-ke’s 155-minute epic once, in Rotterdam. It was screened locally just once, at the Block Museum of Art one Sunday evening last May — 21 months after its Venice premiere — and then only because a fanatically persistent and dedicated 20-year-old programmer named Gabe Klinger (who’s now working at George Eastman House in Rochester) decided to buck the conviction of other local programmers that the film was impossible to acquire. In such cases the impersonal, almost geological sifting-and-sorting process of history in forming the canon counts for almost nothing, and individual initiative and passion count for just about everything. But try telling this to any of the cinema-is-dead people, who can happily assure us the film doesn’t matter because they haven’t seen it.

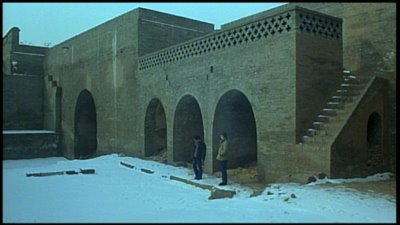

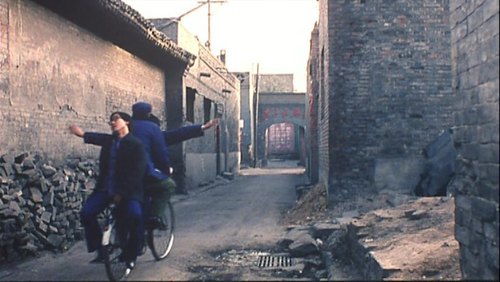

Made in 2000, Platform chronicles the activities of five members of a provincial acting troupe in China over a decade while the country moves from the Cultural Revolution toward capitalism. Jia’s multifaceted view of these changes and his overarching vision — as well as his remarkably choreographed mise en scene, extremely long takes, and intricately plotted camera movements — make this the best mainland Chinese feature I’ve seen. Yet this work, like his earlier Pickpocket, has circulated in China only as a black-market video (his film Unknown Pleasures shows both being sold on the street). Sadly, in the U.S. it’s an even scarcer item.

3. Y tu mama tambien. Apart from having the best sex scenes of any movie I saw all year, this shrewdly plotted, engagingly acted, and exuberantly directed Mexican comedy by Alfonso Cuaron is a prime example of a non-American movie that beats Hollywood at its own game in terms of energy, craft, and showmanship. Other good examples, all on my list of runners-up are The Cuckoo, The Fast Runner (Atanarjuat), Last Orders, Mostly Martha, Nine Queens, Rabbit-Proof Fence, Secret Ballot, and Time Out. I’d be hard put to come up with eight 2002 Hollywood films that were as entertaining as these, and the same virtues are apparent on a smaller scale in the conventional but brilliantly executed short film by Cuaron included on the Y tu mama tambien DVD, a sex farce entitled You Owe Me One.

I never tired of watching the three talented leads in Y tu mama tambien, who embody characters too real to evoke classic Hollywood. But the film does hark back to hallowed movie traditions. One obvious reference, especially if one thinks of the all-knowing offscreen male narrator, is Jules and Jim. I could also cite any number of post-60s road movies as well as the energetic ensemble acting, the feeling for class differences, and the peripheral scenic details of some of the best Warner pictures of the 30s. The casual way this movie strolls away from the tables at a roadside restaurant to show us what the kitchen looks like is emblematic of its taste and mastery, not to mention its political smarts — it has more to say about Mexico incidentally than most movies that harp on the subject. Cuaron is one of those rare birds who can fly back and forth between Hollywood superproductions and down-home efforts — he directed A Little Princess (1995) and Great Expectations (1998) and is reportedly set to direct the next Harry Potter. But I hope he also spends more time in Mexico, because the evidence of this movie is that it brings out the best in him.

4. I’m Going Home. It was gratifying to see the world’s oldest filmmaker finally getting a fraction of his due in this country following the release of one of his most moving and accessible features, which enjoyed a successful extended run at the Music Box in September. With simplicity and patience, Manoel de Oliveira, who turned 94 last month, takes on the subject of aging, focusing on a successful actor at least 20 years his junior (beautifully played by Michel Piccoli) and charting the process of his quiet bereavement after his wife, daughter, and son-in-law die in a car accident — something he learns about offscreen during the opening sequence, just after performing the lead in Ionesco’s Exit the King.

5. Ellipses, Reels 1-4. As I noted when these four short experimental works turned up at Columbia College last April under the auspices of Chicago Filmmakers, I’ve had limited exposure to the late works of Stan Brakhage. (This is mainly because Fred Camper, a Brakhage specialist, has reviewed practically all of his works for the Reader.) These exquisite 1998 films — all silent and mainly nonphotographic “scratch-and-stain” works, apart from the bursts of photography in reel three — qualify as modernist visual music of a particularly rich and intense kind. Like *Corpus Callosum, they suggest the purity of animation without ever quite being animation, at least in the usual sense of that term — though they certainly come closer to it than Snow’s more representational high jinks.

6. Russian Ark. The year’s most staggering tour de force came from Alexander Sokurov — a single-take trek through the world’s largest museum, the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. The film traverses more than two centuries of Russian history, with almost 2,000 costumed actors and extras, three live orchestras, and two foregrounded characters (one on-screen and French, one offscreen and Russian) as dialectically juxtaposed tour guides moving with and around the camera’s complicated trajectories. If the virtuosity hadn’t been so distracting I might have found it easier to engage with the historical commentary, and I might have placed this film higher on my list. Sokurov has clearly been preparing for this film for years; in retrospect, his Elegy of a Voyage looks like a dry run. I won’t be surprised if it takes us a few years to figure out how much of this pageant is impressive grandstanding and how much is something more.

7. The Cat’s Meow. This speculative account of the 1924 death of Thomas Ince aboard the yacht of William Randolph Hearst — who was hosting a party that included Marion Davies, Charlie Chaplin, Elinor Glyn, Margaret Livingston, and Louella Parsons — was a welcome return to form for Peter Bogdanovich, who ironically became more of a pro after he lost his commercial clout in Hollywood a quarter century ago. Derived from an excellent Steven Peros script, this beautifully mounted ensemble period piece proved to have more staying power than Robert Altman’s Gosford Park, perhaps because it has more to say about its characters. The performances of Kirsten Dunst (Davies), Edward Herrmann (Hearst), and Eddie Izzard (Chaplin) are especially impressive, displaying fresh insight into their real-life counterparts. Along with Far From Heaven and 8 Mile, The Cat’s Meow was the best “Hollywood” had to offer in 2002 — though it was actually shot in Germany and Greece, for a modest $6 million.

8. Far From Heaven. I’m still carrying on a friendly quarrel with Todd Haynes’s rewriting of Douglas Sirk and his sumptuous color melodramas of the 50s, which is why I can neither accept nor dismiss this masterful pastiche without qualification. The film moves me, but I’m not sure why. Skeptical friends argue that it doesn’t even have characters in any developed sense, only Hollywood types, and they’re probably correct. Yet the performances of Julianne Moore, Dennis Quaid, and Dennis Haysbert do more things with those types than most actors do with characters. I’m forced to conclude that Haynes has figured out some pretty interesting ways of fucking with my head — trying to be sincere and tell the truth in a language predicated on lies.

9. Germany Year 90 Nine Zero. Two first-rate Godard films came to town this year, but I prefer the earlier and shorter of the two (the other is In Praise of Love), made in 1991, just after the collapse of the Berlin wall, and only an hour in length one reason I prefer it is that Godard still tends to do his best film work (his videos are another matter) when he’s using stars, and this features the last performance of Eddie Constantine, reprising his Lemmy Caution role from Godard’s Alphaville (1965) and many earlier cheap French action thrillers. Another reason is that Godard’s elegies about the weight and losses of history tend to have more bite when they’re open to literary fantasies and comic conceits.

10. 8 Mile. I’m a novice when it comes to hip-hop and less than an enthusiast about Eminem’s politics of resentment, but this movie has so much to say about what it means to be poor, and says it with so much energy and passion, that I was won over. Scott Silver’s script, Curtis Hanson’s direction, and a good cast–including Eminem, Kim Basinger, Mekhi Phifer, and Brittany Murphy — give this Detroit-based update of Saturday Night Fever an undeniable lift.

I can think of at least 30 other good reasons for going to see new movies over the last year, and I’ll list them alphabetically and, except for the first ten, which would make up my list of second-best favorites, without ranking.

Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine is tacky and unfair when it tries to score points against hapless bystanders, but it’s so corrosively accurate about the murderous consequences of gun worship in American culture that I can only marvel at its angry wit and at Moore’s willingness to raise questions he can’t begin to answer. James Benning’s “California Trilogy” — El Valley Centro, Los, and Sogobi, which screened at the Gene Siskel Film Center in March — is 270 minutes of beautifully composed landscape art, with social and political notations that slide in and out of focus. Though I regret the blurry parts, I applaud Benning for persistently grappling with such material over the years.

I caught up with Changing Lanes belatedly and on video. Chap Taylor and Michael Tolkin’s provocative script won me over, for the most part, as did Roger Michell’s fleet direction. The performances, especially those of Samuel L. Jackson and Sydney Pollack, blew me away. Few American movies seem to know how to handle failure as a subject, but this one has lots to say before its implausible redemptive ending. Similarly, Daniel M. Cohen’s Diamond Men — a wonderful showcase for Robert Forster that played all too briefly at the Music Box in February — benefits from Cohen’s own background in the Pennsylvania diamond trade before drifting off into unlikely and fanciful plot twists.

Femme Fatale is my favorite Brian De Palma film, along with Raising Cain (1992) and Obsession (1976). Like these, it has almost nothing to do with reality and everything to do with the playful and artful arrangement of kitsch. Made for less than De Palma’s blockbusters, it also has fewer distractions and lapses, and for once I was delighted by the absence of stars, which kept this thriller lighter on its feet. Heaven, Tom Tykwer’s supple rendering of Krzysztof Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz’s last script, poses an ethical conundrum worthy of Kieslowski’s Decalogue, even if it doesn’t resolve it in a dramatically satisfying manner. It does, however, clarify the Catholicism of the late Kieslowski by showing how close to Hitchcock he could be.

Godard’s In Praise of Love began to open up for me once I started browsing through the subtitled DVD (which you can get only in England), though I’m sure it still has plenty of secrets to impart as well as keep. Kandahar, Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s well-timed inquiry into the misery in contemporary Afghanistan, is one of his most eccentric and original films to date, both because and in spite of its awkward acting and use of English. Bordering at times on black comedy and surreal farce, it’s vastly superior to his misguided documentary Afghan Alphabet, which was shown at the Chicago International Film Festival.

Mostly Martha, about a neurotically driven chef learning to cope with an orphaned girl and an Italian boyfriend, perfectly illustrates the axiom that many of the best Hollywood movies nowadays don’t come from Hollywood — clearly something the Landmark’s resourceful programmers look for. This is a German romantic comedy, which may sound like an oxymoron. But actress Martina Gedeck, under the assured guidance of writer-director Sandra Nettelbeck, brings it off beautifully. Undercover Brother — the funniest satirical comedy of the year and possibly the most good-natured — is so much more inventive than Austin Powers in Goldmember I can’t understand why it withered at the box office, especially since the audience I saw it with was in stitches throughout. Maybe the difference was advertising dollars; if so, it deserved more of them.

Ararat is Atom Egoyan’s first attempt to deal with his Armenian roots since Calendar (still, for me, his best picture). Its engagement with the issue of public indifference to genocide — handled most effectively in a scene with Elias Koteas — continues to haunt me.

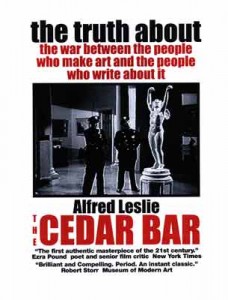

Alfred Leslie’s The Cedar Bar, a highlight at the Chicago Underground Film Festival in August, is a kind of joyful palimpsest. Pieces of a reconstructed 1952 Leslie play about art criticism, videotaped at a staged reading in 1997, are interlaced with wonderful found footage drawn from newsreels, porn films, and Hollywood movies; the result is a kind of irreverent dialogue between these diverse elements.

Code Unknown (2000) — subtitled “Incomplete Tales of Several Journeys” and shown a year ago at the Music Box–is the first of two Michael Haneke films on this list. It’s an interactive jigsaw puzzle, using long takes to chronicle the dispersal of a group of characters on a Paris street across time and space.

Alexander Rogozhkin’s The Cuckoo, shown at the Chicago International Film Festival, is a hilarious comedy in Finnish, Russian, and Sami that’s set in Lapland in 1944. It tracks the mutual incomprehension of a Finnish sniper fleeing his unit in a German uniform, a Russian captain fleeing his compatriots, and a local widow and reindeer farmer who takes them both in.

I was less enthusiastic than some of my colleagues about Zacharias Kunuk’s almost three-hour Inuit epic The Fast Runner (Atanarjuat), yet I can easily understand why it had such staying power at the Landmark: the film is never boring and has all the basic commercial staples, and it’s refreshing to get absorbed in a story without knowing or caring what century it’s set in.

Gangs of New York seems to have been almost everybody’s favorite holiday scapegoat. It’s a mess, but a glorious one — at least for the first half — and Daniel Day-Lewis is terrific. So is Martin Scorsese’s direction, when it isn’t mired in film references or attempts at meaningful historical commentary. (Perhaps its most serious shortcoming is its mangled recounting of the 1863 draft riots.)

Gosford Park is Robert Altman’s best ensemble piece in ages — even better than Short Cuts, in part because it has a better script and is more geared to setting (the country house) and nuance than splashy effects.

Jacques Rivette, le veilleur — Claire Denis’ excellent two-hour 1990 documentary about Rivette for French television — was another Block Films special that came courtesy of Gabe Klinger as part of an ambitious extended series devoted to the late film critic Serge Daney, Rivette’s skillful interlocutor. I’ve never been a big fan of Rivette’s friend and former Cahiers du Cinema colleague Eric Rohmer, but his The Lady and the Duke testifies to his intelligent grasp of history and his ingenuity in using digital video.

I’m anything but a sucker for British kitchen-sink realism, even when it’s delivered by the talented Australian writer-director Fred Schepisi. But in Last Orders, the awesome skills and physiognomies of Michael Caine, Tom Courtenay, David Hemmings, Bob Hoskins, Helen Mirren, and Ray Winstone made me a temporary convert.

Mysterious Object at Noon is the tantalizing title of a remarkable experimental feature by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a Thai director with so many bold and fresh ideas — as evidenced by this film and his second feature, Blissfully Yours — that we’d better learn to spell and pronounce his name. Fabian Bielinsky’s Argentinean caper Nine Queens (2000), whose title refers to a rare set of stamps, is the best movie about con artists I’ve seen since David Mamet’s House of Games. It outclasses Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can by a few leagues, and it makes up for conning us into ignoring a few plot loopholes by predicting Argentina’s economic crisis with uncanny prescience.

I didn’t much care for Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher when I saw it, but Robin Wood’s persuasive defense in CineAction has started to turn me around. (I now suspect that part of my original resistance stemmed from my mistrust of the acclaim it received in Cannes.) Pumpkin — a teen love story with Christina Ricci that chose the highly dangerous strategy of ridiculing its own audience’s hypocritical attitudes about disability — was doomed to box-office failure, but I applaud its nerve in getting me to analyze my own reflexes. I hope the codirectors, Tony R. Abrams and Adam Larson Broder (who also wrote the script), get more chances to show what they can do.

Philip Noyce’s Rabbit-Proof Fence takes up the still controversial Australian reexamination of the government’s treatment of aboriginals. Rolf de Heer’s equally compelling The Tracker (which I hope finds its way to Chicago) suggests a kind of Australian Dead Man; Noyce’s more classical treatment of the theme recalls The Searchers in its epic scope and emotional directness.

Secret Ballot, Babak Payami’s comedy about the national election in Iran, reminded me of The African Queen in its flinty exchanges between a grizzled reactionary soldier and the cheerful, progressive election agent he’s ordered to escort. Hopeful (and groundless) rumors circled the globe that George W. Bush had watched Kandahar, but this is the movie he should have seen instead of Austin Powers in Goldmember while trying to figure out what to do with axis-of-evil types.

Christopher Munch’s The Sleepy Time Gal, which premiered on cable before Facets gave it a second life on the big screen, is better than his second feature (1996’s Color of a Brisk and Leaping Day), though less satisfying than his first (1991’s The Hours and Times). Laurent Cantet’s Time Out, which received an extended run at the Music Box, is haunting and quietly shattering. The last two items on my list — Manoel de Oliveira’s The Uncertainty Principle and Jia Zhang-ke’s Unknown Pleasures — surfaced only at the Chicago International Film Festival, which I hope won’t be our last opportunity to see them.

I don’t want to suggest that this list of 40 in any way exhausts 2002’s most important movie pleasures. I was deeply intrigued by Rebecca Miller’s use of a male narrator in her women-centered Personal Velocity, which is neither conventionally patriarchal nor conventionally feminist; the only reason I didn’t rank this feature higher up is the descending quality of its three episodes, from near perfect to suggestive to querulous.

I also want to note the year’s invaluable revivals and retrospectives, most of them at the Film Center. They include two Anthony Mann westerns (The Naked Spur and Man of the West) in July, Fritz Lang’s wonderfully restored Metropolis in August, and the first comprehensive retrospective in Chicago of the films of Alexander Dovzhenko, in June. My annual F.W. Murnau award for the film or event that most affected my sense of film history has to go to the last of these, which chronicled the defeats as well as the triumphs of the Soviet Union’s greatest film poet. The clearest triumphs — Arsenal (1929), Earth (1930), Ivan (1932), and Aerograd (1935) — are probably the four best films I saw all year.