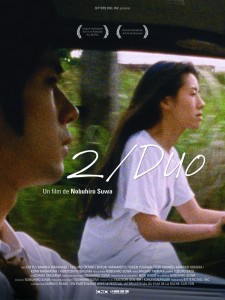

From the February 26, 1999 Chicago Reader. July 2014 postscript: This fascinating and neglected film, still my favorite among the Nobuhiro Suwa features that I’ve seen, has become available on a French DVD released by Capricci — see the first image below — albeit with (optional) French subtitles only. — J.R.

2/Duo

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nobuhiro Suwa

Written by Suwa, Eri Yu, and Hidetoshi Nishijima

With Yu, Nishijima, and Makiko Watanabe.

The first feature of Nobuhiro Suwa, a director of TV documentaries in his mid-30s, 2/Duo (1996) is the penultimate work in the Doc Films series “Japanese Cinema After the Economic Miracle: Masaki Tamura, Cinematographer.” Having seen only one other film in the series — Shinsuke Ogawa’s remarkable two-and-a-half-hour documentary about the lives of farmers protesting the construction of Japan’s biggest airport, Narita: Heta Village (1973) — I can’t give a comprehensive account of Tamura’s work. But judging from these two very different features, I suspect I might recognize his shooting style without seeing his name in the credits. Though Narita: Heta Village is a documentary and 2/Duo a fictional narrative, the style of both displays a highly intuitive engagement with the characters, expressed most clearly in the way Tamura places and moves his camera in relation to them, neither anticipating their actions nor dogging them, but navigating the spaces they occupy with an intelligence that manages to project empathy as well as independence — a rare combination.

I owe this discovery to the programming initiative of Chika Kinoshita, the graduate student in film at the University of Chicago who organized the retrospective, because my enthusiasm for 2/Duo preceded any awareness of Tamura’s contribution to it. I first saw this 35-millimeter feature on video at the Rotterdam film festival in early 1997. About nine months later I saw it on film at the Viennale, a Vienna film festival that Suwa attended. I was the head of a jury there, and we wound up giving our main prize to it.

Now that I’ve seen 2/Duo a third time — on video, a far from ideal way to view a film that depends on visual nuance — the importance of Tamura’s personal camera style in this stirring and volatile experiment is fully evident to me. His way of shooting an informal political discussion in Narita: Heta Village sometimes involves panning away from the person speaking — displaying an attentiveness to group interaction that finds responses to talk as important as the talk itself. And the placements and displacements of his camera in 2/Duo are often extraordinary in elucidating the essence of a scene. What initially might seem a perverse choice of camera angle turns out to be a highly original and compelling definition of where documentary and dramatic truth might be found — a definition that resculpts conventional priorities regarding how a particular scene should be read, thereby encouraging us to reconceptualize its meaning.

To the best of my knowledge, the Sunday screening of 2/Duo will be its first and only airing in North America. That’s not surprising given the current state of foreign-film distribution and festival programming — most of it determined by the relative familiarity rather than the freshness and novelty of the works. Actually it’s a miracle that the film has turned up here at all. I suppose one could argue that a single screening in North America of an esoteric Japanese feature can’t possibly amount to much, but I don’t for a second believe this — particularly because a major inspiration for 2/Duo was an esoteric French feature that Suwa somehow managed to see.

In any case, though I was certainly struck by the cinematography of 2/Duo in Rotterdam and Vienna, my impulse was to attribute it chiefly to the director. Most of the dialogue in the picture is improvised by the actors, and because I knew that Suwa’s background was mainly in TV documentaries, I assumed that he was the one mapping out the camera’s placements and sometimes spontaneous trajectories. Yet it takes no credit away from him as a filmmaker to acknowledge the crucial contribution of Tamura; indeed, having the foresight to use Tamura as an integral part of his design is central to Suwa’s achievement.

The plot of the movie focuses on the breakup of a young couple living together — a woman named Yu (Eri Yu) who works at a boutique and a man named Kei (Hidetoshi Nishijima) who’s unsuccessfully pursuing a career as an actor. The acute sensitivity and volcanic intensity of the psychodrama in their scenes together reminded me of John Cassavetes’s Shadows, and I asked Suwa whether Cassavetes was an influence. His response was an emphatic and somewhat irritated no; it seemed that many others had asked him the same question, perhaps based on the popular misconception that Cassavetes’s films were improvised. But when I tentatively ventured the name of Jacques Rivette, Suwa’s eyes lit up and he nodded vigorously.

I no longer recall whether Suwa cited as his inspiration Rivette’s L’amour fou (1968) or the 12-hour and 4-hour versions of his Out 1 (1971 and 1973). L’amour fou, which also deals with the breakup of a couple, seems the more obvious reference, but my dim memory suggests it was actually one of the latter. I’ve since been told that all three of these features — Rivette’s major experiments to date involving actor improvisation — have been virtually impossible to see in Japan, so perhaps Suwa saw them abroad or on an imported video. Most of Rivette’s subsequent films are currently available in Japan on video — evidence that in spite of the corporate stranglehold on film that prevails across the planet and makes a large portion of the most valuable artistic work extremely difficult to see, certain things still manage to sneak through.

I don’t mean to imply that Suwa’s film is even an approximate imitation of Rivette’s work. Rivette and his cast scripted L’amour fou mainly day to day; the actors in Out 1 were responsible for their own characters and dialogue, and Rivette organized their encounters around a few sketchy plot elements. Both these projects also involved shooting documentary footage of stage actors and directors during rehearsals. In the case of 2/Duo, there was a script by Suwa that the actors were asked to read and then forget — a method that superficially resembles the preparation of the celebrated kitchen sequence with Agnes Moorehead, Tim Holt, and Ray Collins in Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons. As Welles described his work with the actors on that scene, which grew out of rehearsals: “The rhythm of it was all set. The precise words weren’t.” In 2/Duo — where the plot is much simpler, and the actors don’t have to be as concerned with exposition — the method becomes much more radical. Critic Donald Richie says, “Through rehearsals [Suwa] molded [the actors’] version of the forgotten script — all movement, all dialogue their own. The cameraman, Masaki Tamura…was as much a part of the action as the actors were. He watched patiently, always in control, always generously giving up control. Working with intelligence and tact, Suwa made a common situation extraordinary.”

In addition, at four intervals over the course of the film, Suwa, offscreen, interviews each of his two main actors in character about her or his feelings and motivations. The main crisis in the relationship between Kei and Yu — which occurs shortly after Kei turns up for a TV acting job where he has a single line of dialogue, only to be told that his line has already been cut from the script — is precipitated when he impulsively proposes marriage to her in a cafe. She responds in a characteristically Japanese manner, by giggling nervously, then asks him, “What’s the next line?” — implying that he’s still rehearsing a part. When he says there isn’t a next line, she leaves the cafe without responding. Suwa interviews Yu immediately after this scene, asking her why she didn’t say anything; she says she doesn’t know, but then suggests that she was thrown by the proposal because she doesn’t think Kei really wants to get married. “Will you ask Kei about it?” Suwa asks her. “Yes, maybe I will,” she says, and in a later scene she does, only to be violently rebuffed.

In a similar fashion, Suwa subsequently interviews Kei about his desire to be an actor — a short scene that increases the documentary effect of the proceedings because of course Nishijima is an actor. Still later, after Yu has left Kei and quit her job, Suwa interviews Kei about his feelings for her and about how it feels to be living alone in the flat he once shared with her. And shortly before the end of the film, he interviews Yu about her conflicted feelings regarding Kei. Nothing said in these segments ever registers as definitive or conclusive, but it’s part of the power of Yu’s and Nishijima’s intuitive performances to suggest that the mysteries of love and relationships can only be explored, not solved; the interviews are merely ways of continuing the exploration by other means.

How does Tamura’s remarkably unorthodox and inventive camera style inflect this troubled and troubling story? Consider the intricate coziness of Japanese architecture, especially the interiors. When I briefly visited Japan for the first time last December, I spent most of my final evening there in a legendary bar called La Jetée — named after Chris Marker’s short SF film of the same title, the source of 12 Monkeys — and was surprised to discover it can seat at most about ten people. Consisting of a counter and a single table, it isn’t even the smallest bar in that quarter of Tokyo, yet it has cropped up as a location in several films. It’s characteristic of Japanese cinema to create a mise en scène in relatively confined spaces — perhaps as a kind of disciplinary challenge, like haiku, in which restrictions play as pertinent a role as opportunities. (By way of illustration, the most impressive piece of Japanese film criticism I’ve read, Shigehiko Hasumi’s elegant book about Yasujiro Ozu, draws attention to the structural importance of the absence of staircases in most Ozu films.)

The main location in 2/Duo is the cramped one-room, second-floor apartment shared by the couple, with its large mattress, minimal kitchen, and balcony occupied by a washing machine and a clothesline. Tamura has devised various ways of filming this space so that it functions as a shifting and evolving presence, a location that never registers as monotonous or predictable. But he also has a tendency to avoid filming either character frontally; they’re usually turned slightly away from us as well as from each other. The usual Hollywood editing syntax that handles two people conversing — a frontal shot followed by a frontal reverse shot — is consistently avoided, and the implications of this avoidance become even clearer when the film moves outside the flat. When Kei proposes to Yu, for example, he’s seated across from her at a cafe table, but the camera is positioned directly behind his head and catches her face only in three-quarters profile. Similar framings recur throughout: the film’s opening shot, which shows Yu entering the frame to sit on the mattress next to Kei, is angled so that a corner of the wall blocks most of her body once she’s settled into position, while Kei is fully visible, though from a somewhat oblique angle.

The strategy of keeping key elements out of the frame — most of Yu’s body during the opening shot, Kei’s face in the cafe — is tied to these characters’ psychological concealments and repressions, a strategy that only underscores how conventional filmmaking cheats on the truth in the interests of legibility and more satisfying symmetries and closures. Keeping certain elements beyond our grasp can increase the intensity and creativity of our involvement –characters in this film often come across as startlingly lifelike precisely because they’re composed of shifting kaleidoscopic balances between mystery and clarity, evasion and confrontation, communication and withdrawal. In one scene Kei, who depends on Yu for financial support, proposes that he do all the housework while she goes off to her job, then goes into a raging tantrum, throwing objects and emptying food packets on the floor. Later, a lunch prepared by Yu for a few of her friends quickly turns into an ugly and embarrassing scene, and the friends are asked to leave.

A genuine sense of existential danger and possibility courses through practically every scene in this film, with casual joking sliding into aggression or an argument quickly dissolving into affection. Tenderness and brutality become not so much two sides of the same coin as two extremes along a spectrum. Yu and Kei clearly love each other and just as clearly can’t bear to be together — a common enough conundrum, but one that’s rarely treated with this kind of passionate complexity and explosive energy. Suwa and Tamura have made it real and vital by fashioning along with the actors a style designed less as discovery than as pursuit — and thanks to their efforts, we become committed pursuers as well.