This essay, a revised and updated version of my article “The Seven Arkadins,” was commissioned by the Australian DVD label Madman for their DVD of Orson Welles’ Confidential Report, released in 2010. — J.R.

Mr. Arkadin “was just anguish from beginning to end,” Orson Welles told Peter Bogdanovich in their coauthored This is Orson Welles, and probably for this reason, Welles had less to say about this feature — known in a separate version as Confidential Report — than any of his others, either to Bogdanovich or to other interviewers. Editing This is Orson Welles in its two successive editions took me the better part of a decade (roughly, 1987-1997), and one of the biggest obstacles I faced throughout this work was the paucity of specific details that Welles was willing to offer about this film. It was plainly too painful a memory for him to linger on, and he even spoke of being blocked in remembering certain particulars.

Broadly speaking, the features of Welles fall into two categories: those he finished and released to his satisfaction and those he didn’t. In the first category are Citizen Kane, Macbeth, Othello, The Trial, Chimes at Midnight, The Immortal Story, F for Fake, and Filming “Othello”. And in the second batch are The Magnificent Ambersons, It’s All True, The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin/Confidential Report, Touch of Evil, The Deep, The Other Side of the Wind, The Dreamers, and Don Quixote.

Is it correct to regard the second ten as unfinished? I believe it is — at least if we continue to regard them as films by Welles, and agree with Welles that the editing was crucial to what made them his. (Although he came relatively close to finishing half of the latter ten — Ambersons, The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Touch of Evil, and Quixote — we don’t have access to any of those cuts.) Yet the standard practice has been to regard all of the ones released when he was alive as finished, regardless of whether he approved them or not. This places the matter in the hands of distributors, and every version of Mr. Arkadin, including Confidential Report, in the category of a finished work by Welles. But I think Welles himself would have disagreed.

Trying to expand the minimal material I had about Mr. Arkadin and Confidential Report through independent research, I eventually wrote and published an article entitled “The Seven Arkadins” roughly halfway through my labors on the Welles/Bogdanovich book, during the early 1990s, an updated version of which can be found in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles (Berkeley: University of California Press), a piece which I could then reference and draw from in my editor’s notes in This is Orson Welles. (Some portions of that article are reycyled here.) But it wasn’t until the French Welles scholars Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas, during research for their own book Orson Welles at Work (London/New York: Phaidon, 2008), uncovered the correspondence between Welles and the film’s executive producer, Louis Dolivet, that much of the checkered history of this film and its multiple versions was uncovered. (Based in part on this research, Thomas compiled a six-page chronology of Mr. Arkadin for the 2006 Criterion DVD box set, The Complete Mr. Arkadin.)

Even more mysterious than the film and its writer-director-star was Dolivet, a Romanian with French nationality and a former member of the Comintern who served as Welles’ political mentor in the United States during Welles’s most politically active period, in the mid-1940s, when Welles was writing a regular column for the New York Post (as well as editorials for Dolivet’s Free World magazine), was campaigning for the re-election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had a weekly radio show of political commentaries, and was supporting the League of Nation and the creation of the United Nations. Married in the 40s to the American stage actress Beatrice Straight (who would play Goneril to Welles’ King Lear on American television in 1953, and would later win an Oscar for her supporting role in the 1976 Network), Dolivet was obliged by his Communist past to flee to Europe, where his friendship with Welles led to a multifaceted partnership during which he became a film producer for the first time, on Mr. Arkadin/Confidential Report.

In late 1953, Welles signed an agreement with Dolivet and sold the rights to his script to the newly-formed, Tangiers-based company Filmorsa, put together by Dolivet with the help of French investors. The film became a Spanish coproduction in January 1954; Welles started shooting in Spain later the same month, and shifted operations during the spring, first to the French Riviera, then to Munich, and finally back to Spain again. By June, when Welles had started to edit the footage, he had signed over the rights of several other film projects to Dolivet. At this point, the film was supposed to have been ready in time for the Venice film festival in September, but eventually the film was withdrawn and Welles wound up shooting additional scenes in France in September and October. In fact, the film wouldn’t premiere for almost another year (on August 11, 1955, in London.)

Dolivet also plays a small cameo in the film, appearing at almost precisely the halfway point. Guy Van Stratten (Robert Arden), a petty American black-market smuggler who gets hired by the title hero (Welles) — a mysterious Russian tycoon and widower whom Van Stratten tries to blackmail on the basis of limited information he stumbles upon, meanwhile trying to court his daughter Raina (Paola Mori, Welles’ fiancée at the time). Arkadin paradoxically hires this own prospective blackmailer to research his own buried past, claiming that he has amnesia about how he acquired the basis of his fortune. Van Stratten eventually winds up on the trail of one of Arkadin’s former associates, the Baroness Nagel (Suzanne Flon), whom he traces to Paris. There he briefly interviews Dolivet on the street, a cigarette dangling out of the corner of his mouth, who describes the Baroness as “a vendeuse…a saleswoman”.

Dolivet would later serve as the executive producer on Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle and Parade. Some of his own mysterious escapades in international financing are addressed, at least indirectly, in Jean-Luc Godard’s latest feature, Film Socialisme, which quotes an image of Dolivet’s Arkadin cameo and implies that he might have even served as one of Welles’s models for Arkadin himself. To quote Godard (in conversation with Daniel Cohn-Bendit): “After the invasion of France by the Germans, the Komintern transferred the gold from the Spanish bank over to Russia; they loaded it in Barcelona onboard the France Navigation company, which belonged to the French Communist Party. But upon arriving in Odessa, a third of the gold disappeared, and a second third again disappeared before arriving in Moscow… I imagined that the Germans had infiltrated the ship, that they had taken a portion of it — that’s how the old French policeman tells it in the film. But the young Russian girl who goes rummaging through the archives figures: the third that’s missing, Komintern took it, and the rest wound up in Louis Dolivet’s pockets, whose fortune can’t be explained otherwise…”

Welles’ previous feature, Othello (1952), which took him almost three years to make, marked the beginning of a radical new phase (and corresponding new style) in his career as a filmmaker after he completed two separate versions of Macbeth, his penultimate Hollywood feature, in the late 1940s. Shooting Othello in diverse North African and European locations after the financing for a French studio shoot suddenly collapsed when the producer went bankrupt, Welles would periodically suspend production while trying to acquire more funding, creating a new style of patch-quilt editing in the process. Various changes in his casting of Desdemona during this extended adventure also made a certain amount of reshooting necessary. Against all the odds, this was a reckless experiment that eventually triumphed when the film shared the top prize at Cannes in 1952, but in this case, at least, Welles had Shakespeare’s own play as a kind of safety net for his improvisations in shooting, mise en scène, and editing.

During this period, Welles also landed a crucial acting job in what would prove to be the most popular film he ever worked on, playing Harry Lime in The Third Man. This led to a low-budget radio series based around the various criminal exploits of Lime, an American adventurer set loose in postwar Europe, which Welles helped to write, and his original script for Arkadin grew out of a few episodes in this radio show. The serious troubles leading to all the “anguish” started when Welles tried to set up a globe-trotting plot and style of shooting that resembled his impromptu methods on Othello, working again with a minimal budget, but this time with an original script. Many of his first choices for the casting — including, among many others, Marlene Dietrich for a character named Sophie, and Michel Simon for a character named Oskar — were eventually abandoned and many last-minute replacements had to be sought. Some of the major locations that Welles had in mind also had to be changed once the film became a Spanish coproduction, necessitating more shooting in Spain than he originally envisioned. The costume ball where Van Stratten originally meets Arkadin had to be shifted from Venice to a castle in Spain, which led to Welles’s conceit of Goya-derived costumes and masks at the ball. (From Welles’s original script, Masquerade, dated March 23, 1953: “This is clearly an attempt on Arkadin’s part to out-do the famous Bestigui Ball, and is in fact, in many ways, a duplication of it. . . . The canals are filled with illuminated gondolas carrying Arkadin’s guests, all in costumes of the Venetian 18th century….”) And various other locales were changed for practical and logistical reasons, e.g., the pawn and junk shop of Burgomil Trebitsch (Michael Redgrave) in Copenhagen was originally supposed to be in Marseille, and, as it turned out, some of the fictional settings that had to be simulated in a studio in Madrid included a hotel in Mexico City, the docks in Naples, Arkadin’s yacht, the interior and environs of his Spanish castle, a café in Tangiers, a nightclub on the Riviera, and the inside of a Munich cathedral. And because the film was a Spanish coproduction, two scenes had to reshot using Spanish actresses—Amparo Rivelles as the Baroness Nagel (instead of Suzanne Flon), and Irene Lopez Heredia as Sophie (instead of Katina Paxinou), and a separate editor was assigned to the Spanish version. (At least two separate versions of this Spanish Arkadin survive today.)

Part of the anguish that Welles experienced had to do with the nightmare of acquiring work permits and visas at various stages for his international crew (“I had a French cameraman, an Italian editor, an English sound engineer, an Irish script girl, a Spanish assistant,” Welles said; the film’s rushes, moreover, had to be developed in a French lab.) In various attempts to raise more money, a ghostwritten novelization of Masquerade by French critic Maurice Bessy was commissioned by Gallimard and then serialized in 59 installments in the French newspaper France-Soir (later to be translated into English and published again under Welles’ name — although a separate and much shorter five-part English-language serial of the story would also be written by Welles himself, for the London Daily Express). And during this same period, Welles was also planning many other projects with Dolivet. But, more generally, Welles was constantly revising the script during both the shooting and editing — not only in terms of scenes and how they were ordered in relation to flashbacks, but also in terms of dialogue, because he wound up dubbing and redubbing many of the actors himself: not merely Grégoire Aslan, Mischa Auer, and Frédéric O’Brady, but also some of the incidental voices (such as the announcer over the PA system at the Munich airport).

Even though Welles excelled at adapting to many last-minute changes of this kind in radio, theater, and film throughout his career, many of the challenges posed by Arkadin, no doubt exacerbated by the difficulties of working with a first-time producer, proved to be insuperable, leading to the “anguish from beginning to end” that he would speak about later, and his friendship with Dolivet ultimately wound up as one of the major casualties. But the research of Berthomé and Thomas has revealed that a simple account of Dolivet forcibly snatching the film away from Welles’ creative control is an oversimplification of a much more complicated and troubled deterioration of a friendship. In January 1955, for example, Welles, who by then was involved in the preparation of many others projects with Dolivet, including a TV series called Around the World with Orson Welles, agreed to withdraw from the film’s postproduction, with the understanding that he would step in towards the end of the editing to do a final polish. And only about two weeks before the film premiered in London, in a version that Dolivet cobbled together in Welles’s absence, even though Welles himself came up with this title — Welles refused Dolivet’s offer to sell him the full rights to the film, which would have entailed paying back all the money invested and assuming all of the debts, but would have also given him total, creative control. Welles’s reasons for rejecting this offer haven’t been recorded, but one can imagine that the many financial burdens that would have been involved must have given him some pause. And the growing alienation between him and his producer clearly made all their negotiations difficult. In September 1961, Welles was even taken to court in New York by Dolivet for breach of contract, although three years later, at Welles’s urging, Dolivet finally agreed to drop the lawsuit.

***

Despite (or, rather, because of) all these vicissitudes, the bottom line about Mr. Arkadin /Confidential Report is that insofar as it’s “a film by Orson Welles,” it remains unfinished and incomplete in all its versions — making it all the more confusing (if none the less understandable, at least from a capitalist and consumerist standpoint) that Criterion’s box set is called The Complete Mr. Arkadin. And thanks to much of this confusion, this is the second essay I’ve published defending a particular version of Arkadin over all of the others. The first was written in late 2005, to accompany the Criterion box, when I defended the so-called “Corinth version”, named after the film’s original U.S. distributor — even though a few bits that Welles had mentioned in passing to Bogdanovich, such as Arkadin’s “Georgian toast” about a dream set in a cemetery, were missing from this version.

To confuse matters further, the present essay is also the second one I’ve published about Confidential Report. The first one was written in late 1991 or early 1992, to accompany the Voyager laserdisc, when I still believed that the “Corinth version” was the best one available, although the people at Voyager wouldn’t allow me to say so, again for consumerist reasons. Today, however, I’m less sure about this preference.

The advantage to be found in the “Corinth version” is that this one comes closer to the flashback structure that Welles finally settled on during his own editing of the footage — which is why Bogdanovich expended a lot of effort to ensure that when Arkadin opened very belatedly in the U.S., in the fall of 1962, it was in this version. But, as François Thomas has argued, Confidential Report is preferable if one chooses to privilege the final stages of Welles’ editing, including his sound editing, before he lost control over the picture, over the flashback structure. And insofar as one agrees with Welles’ own oft-stated conviction that the art of cinema is the art of editing, the least preferable version is the so-called “comprehensive version” edited for the Criterion box set by Stefan Drössler and Claude Bertemes, which tends to ignore Welles’ own editing for the sake of including as much of the footage that he shot as possible, arranged in the way that the editors like best — a cut which might be called the consumerist, collectible Arkadin as opposed to the Welles Arkadin. And once one opens the door to this sort of intriguing but arguably hopeless exercise, an infinite number of Mr. Arkadins then becomes possible — except, of course, for any of the ones that Welles himself might have made. If “a fool” — according to Gregory Arkadin himself, mordantly addressing the Baroness Nagel — “is a man who pays twice for the same thing,” then one might say that a collecting fool — that is to say, a ravenous cinephile — can be described as someone who keeps on paying for variations on the same thing any number of times.

***

While researching Arkadin in the early 90s, I had the good fortune to land a telephone interview with Patricia Medina. I was surprised to learn from her that she’d never seen the film, but considering that she was the wife of Joseph Cotten and thus a long-term friend of Welles, I later assumed that this might have been due to a sense of loyalty towards his “anguish” about how the film wound up. She was under contract to Columbia at the time, and when Welles phoned her in London to ask her to play Mily, she had very little time to shoot because she was due back in the states to act in something else. Welles replied jokingly, “Then we’ll have to kill you off.” (Mily’s murder, alluded to offscreen in the film, was never shot in any form.) Medina flew to Madrid and all her scenes were shot there, most of them in a studio, over about ten days.

Overall, she remembered the shoot as a happy event. The first scene she did was on the yacht with Arkadin. The night before shooting, Welles showed her the set, asking scornfully, “Doesn’t it look just like the Staten Island Ferry?” The yacht set was up in the air, so one had to climb up into it. After Medina returned to her hotel, Welles phoned to ask her if there was anything in her hotel that “belonged in a yacht.” She looked around and found very little. When she arrived for filming the next morning, she discovered that Welles had been up all night redressing the set with furniture temporarily swiped from the lobby of the Madrid Hilton, where he himself was staying. He announced that they had time for only two takes because the furniture had to be returned before it was missed. (One detail in this scene was improvised: Mily saying “Shut up!” to a screeching bird in a cage.)

When she left for the States, Welles asked her to send a still of herself that could be blown up for a poster advertising Mily as a bubble dancer. She neglected to do so. When she arrived in Paris sometime later to do the dubbing with Welles, she was appalled by the still that he had found and used on his own. (When Van Stratten learns of Mily’s death later in the film, this picture recurs in some versions, identified in the dialogue as “the only available photo taken before death.”) And that marked the end of her involvement; much later she was contacted by Dolivet to act in some additional scenes, but after learning that Welles wouldn’t be directing them, she refused.

***

Another major difference between Confidential Report and all other versions of Arkadin is a block of offscreen narration by Van Stratten, probably not written by Welles and quoted below, that accompanies four shots of him approaching a rundown house in the snow (shots visible in all of the film’s versions). Lamentably, the end of this narration blunts the power of the film’s most beautiful camera movement, a backward retreat down a dark tunnel of a hallway:

Here I am at the end of the road. Naples, France, Spain, Mexico, and now Munich. Sebastianplatz 16. In the attic of this houselives Jakob Zouk, a petty racketeer, a jailbird, and the last man alive besides me who knows the whole truth about Gregory Arkadin.My confidential report is complete now. My original fee for this job was $15,000, and it looks like a little bonus will be tossed in — like a knife in my back. But Zouk will get his first unless I can save him. And then me — the world’s prize sucker.

In the spring of 1999, when I was invited to the Munich Film Archive for help in sifting through some of the Welles material deposited there by Oja Kodar, I was amazed to discover that not only was Sebastianplatz 16 a real address; it was still standing, in a rehabbed but recognizable state, directly across the street from the Archive. Since this Archive was founded in 1963, the proximity was purely coincidental.

***

A Tentative Critical Summary: “Give the Gentleman His Goose Liver”

In his preface to the English translation of André Bazin’s Orson Welles, François Truffaut divides all of Welles’s films into those made with his right hand and those made with his left hand, adding, “In the right-handed films there is always snow, and in the left-handed ones there are always gunshots; but all constitute what Cocteau called the ‘poetry of cinematography.'” Mr. Arkadin/Confidential Report is the only Welles film with both snow and gunshots, but I think Truffaut is probably correct in considering it one of the left-handed films. Its moments of poetry are intense and indelible, but the feeling of chaos that it imparts, while fundamental to this poetry, is at times less than adequate to the more prosaic needs of the narrative. Eric Rohmer was right to classify the film as a tale or fable rather than a realistic story or a thriller, and it might be argued that the relative hospitality of French criticism toward unrealistic narrative helps to account for the relative favor it has found in French criticism. (In 1958, Cahiers du cinéma’s editorial board collectively decided that Confidential Report — the only version of the film that they knew at this point — was Welles’s greatest film, and the only that belonged on their list on the dozen greatest ever made.)

Anglo-American critics have generally been put off by the same elements. Dwight Macdonald characteristically complained about the lack of attention paid to Arkadin’s business dealings and the visible artifice in Welles’s makeup for the part; others have seized on the superficial plot resemblances to Citizen Kane to berate the film for its incoherence, its performances, and/or its production values.

I share some of these biases, although a few seem misplaced. For all the film’s lack of realism, it still has some validity and interest as a cold war allegory, as James Naremore has suggested. Naremore notes Robert Arden’s “uncanny resemblance to a young, athletic Richard Nixon,” and if one connects this with Arkadin’s resemblance to Stalin — a resemblance underlined by Arkadin’s Georgian background and his habit of killing off former associates and witnesses — the struggle of the two over Raina, who might be said to represent Western Europe in the mid-50s, is full of suggestive and subversive possibilities. The fact that Arkadin and Van Stratten are presented as moral equivalents — older and younger versions of the same unscrupulous lout — is central to this reading.

Arden’s performance as Van Stratten is commonly singled out for abuse, even by most of Welles’s defenders, but after repeated viewings it seems to me that it’s the unsavoriness and obnoxiousness of the character rather than the performance itself that is responsible for much of this attitude. A comparable syndrome applies to Tim Holt’s George Minafer in The Magnificent Ambersons: because both characters occupy the space normally reserved for charismatic heroes, we feel we’re supposed to like and/or sympathize with them, and when their respective films make this impossible, we wind up blaming either the actors or Welles’s casting rather than accept the premise that we’re meant to have a difficult time with these people.

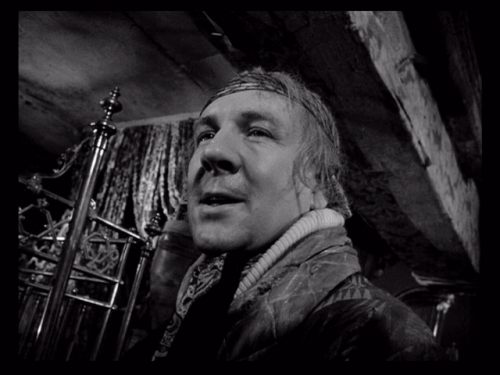

This is not to suggest that the performances in Confidential Report are above criticism. I agree that the film has one debilitating performance, but this is given by neither Arden nor Paola Mori (who may be relatively unskilled — which may partially explain why she was dubbed by Billie Whitelaw — but still seems quite adequate to the demands the script makes of her). I’m afraid it is given by Welles himself. The falseness of his makeup and the variability of his Russian accent can’t be rationalized by the elusiveness of Arkadin’s character, because no norm is ever established for these traits to deviate from. One can accept the film’s premise of presenting us with a gallery of grotesques, but not a title ogre whose face is little more than a Halloween mask. At separate junctures, Arkadin is linked to Neptune and Santa Claus, and at his own ball he hides behind a mask; most of the plot is devoted to uncovering his original identity as a lowlife named Akim Athabadze. But even this latter phantom, glimpsed in a faded photograph belonging to Sophie, lives more in our minds than Gregory Arkadin does on screen. (Mainly this is because of Sophie herself; she and Zouk wind up providing most of whatever soul the movie has, thanks in large measure to Paxinou and Tamiroff.) Welles appears to have conceived of Arkadin as a tissue of paradoxes, but his own performance, even if it contains some lovely line readings, doesn’t bridge or embrace those paradoxes. At best it only alludes to them.

Perhaps the most underrated feature of Confidential Report is Paul Misraki’s wonderfully evocative and rhythmic score, which sometimes plays even more of a shaping role in the film than the plot, dialogue, or mise en scène. Nostalgia for a lost innocence plays as important a role here as it does in Kane, Ambersons, and Chimes at Midnight (where it is also tied to snow), although the site of this innocence is less localized than the nineteenth century or the Middle Ages is in those films (not to mention Tanya’s bordello in Touch of Evil). Like Arkadin himself, it’s anywhere and everywhere, sometimes where we least expect it. It’s Christmas and goose liver and the last time someone said “Come to bed” to Jakob Zouk. It’s the youths and romantic yearnings of the Baroness Nagel and Sophie, and a scruffy little Salvation Army band in the street. More mysteriously and disturbingly, it’s the sudden, irrational, backward retreat of the camera down a dank tenement corridor, into a dark womb of oblivion.