From the February 18, 2000 Chicago Reader. This piece is reprinted in my Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia.— J.R.

Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Martin Arnold

With Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, and Fay Holden.

Wearing suspenders, Mickey Rooney as Andy Hardy steps behind his mother (Fay Holden), clutching her left shoulder and right forearm with his two hands, and firmly kisses the back of her neck while she slowly nods her head with a stoic, worldly-wise expression. In a series of stuttering, staccato jerks, he does the same thing again, to the throbbing strains of eerie, ghostly music. Then he does it a third time, pausing first to rock back and forth from one foot to another a good many times, as if he had ants in his pants. When he kisses the back of his mom’s neck this time, his lips seem to remain glued there. This embrace, his barely perceptible jaw movements, and her steadily bobbing head all conspire to suggest something vaguely obscene and depraved. Could Andy have become some kind of Dracula, sucking blood from his mother’s neck? Or do the slow pumping rhythm and repeated nervous thrusts represent some kind of sexual motion?

When Andy breaks away, this gesture too is repeated compulsively, his mouth twisting back and forth between amorous solemnity and a delighted grin, as if he couldn’t make up his mind about how he feels. Finally, when he moves away from his mother entirely, his body turning in a semicircle, the camera cuts to a new and more distant angle that shows he’s wearing an apron; apparently he’s been washing dishes at an unseen sink. Her eyes steadily follow him as he moves, and she smiles. Picking up a plate and a towel, he turns further around in the same direction, showing his back to us and his mother, stepping toward a table with a checkered tablecloth. Meanwhile his mother, looking at him adoringly, says something both wordless and inhuman.

I’m trying to describe the first two and a half minutes of Martin Arnold’s creepy 15-minute experimental film Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy (1998), but I can’t be confident that my account is either complete or entirely accurate. For one thing, the somewhat stocky, stolid older woman Andy Hardy kisses may not be his mother; theoretically it could be his Aunt Milly, another character in the series. I know that MGM released 15 Andy Hardy pictures between 1937 and 1946 — 7 in 1938 and 1939 alone — and a final one in 1958. But with the possible exception of the last, I don’t believe I’ve seen any of them apart from occasional snatches while channel surfing. I’m not even sure which of the Andy Hardy features furnished the extracts for this film — assuming it was only one — though the presence of Judy Garland in later segments of Alone narrows the possibilities to three: Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), Andy Hardy Meets Debutante (1940), and Life Begins for Andy Hardy (1941) (Garland plays a character named Betsy Booth in all of them).

And finally, because I never saw the sequence before Arnold got his hands on it, I don’t know with certainty if the perverse meanings he’s gleaned from it grow out of only one gesture. Does Andy Hardy simply and briefly peck at his mother’s neck in the course of washing dishes? That’s what it looks like, but I can’t be sure.

Arnold — an Austrian who manipulates fragments of black-and-white Hollywood features through optical printing and editing — is presenting a program of his films, including Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy, on Friday, February 18, at Columbia College’s Ferguson Hall through the auspices of Kino-Eye Cinema. Two earlier items on the program are described as parts of a trilogy with Alone, though they seem to me merely setting-up exercises by comparison: neither packs the same punch, establishing most of Arnold’s procedures but doing much less with them. These films lack Alone’s narrative and internal complexity — its ability to connect a good many scenes and characters while actually telling a story part of the time.

Piece touchée (1989, 16 minutes) shows a woman reading in a chair as a door behind her repeatedly opens and closes; a man finally enters and engages in some kind of interaction with her. It’s difficult to tell what it is because Arnold essentially turns the two figures into epileptic dolls with his relentless repetitions and reversals: he prints the same shots backward and/or upside down in rapid alternation with the originals, producing various aggressive flicker effects. (According to the French rock magazine Les Inrockuptibles — which reviewed Arnold’s short films earlier this month, just after their video release in France — this fragment is drawn from Joseph M. Newman’s 1954 police procedural The Human Jungle.)

Passage à l’acte (1993, 12 minutes) is much more interesting to me because its source is recognizable, which makes Arnold’s perversions more diabolical. It takes a few short fragments of a scene from To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), with a father (Gregory Peck) and mother figure, little girl, and little boy sitting at the breakfast table. Arnold submits this material to the same sort of looping, inverting, and scrambling as in Piece touchée, but this time the effect is much more bizarre.

To Kill a Mockingbird is certainly ripe for deconstruction: this rather self-satisfied 1962 adaptation of a pretty good southern novel occupied 34th place in the American Film Institute’s stupid poll of the best American movies — and was ludicrously praised by Jack Valenti as the first Hollywood film to deal honestly with racial issues. But what Arnold chooses to deconstruct is to all appearances a fairly ordinary family scene. The boy runs out through a rattling screen door at the beginning and later returns; at the end, both the boy and girl leave by the same door, though the girl first does something with the lower part of the door and then either kisses her father or whispers something in his ear. (In the background of many of the shots with the boy is a black cook, seen from behind.)

It’s all quite obscure in terms of narrative, but most unsettling of all is the way various manipulations transform the dialogue into a series of unearthly and meaningless noises. What may start out as “yes” from Peck is quickly transmuted into “byah,” “weh,” “bam,” and “jam,” immediately followed by volleys of what sound like gunshots or an onslaught of attacking woodpeckers, then further remarks from Peck that sound like “haffa-now,” “flupper,” and “patoot.” Then there’s a frenetic dialogue between the boy and girl in which he seems to be saying “hoy-ya” and she quacks back, followed by repeated rapid cuts between the woman raising a cup of coffee to her lips and the girl doing the same with a glass of milk.

All this unnervingly dehumanizes the actors as well as the characters they’re playing. Arnold’s distortions remind us of the mechanical nature of film projection, which we take for granted as representing reality: altering this mechanism can turn people into inhuman geeks at the drop of a hat. Alone carries this principle even further — most notably with Judy Garland’s singing, which moves in and out of recognizable as well as freakish registers — and makes its point even more effectively by allowing us to comprehend a few of the words being uttered by Garland, Rooney, and an unidentified actor. (Indeed the title, Alone, comes from one repeated recognizable portion of her song.)

Does this progression make each film in the trilogy “better” than the last? For me it does: the recognizable movie and actor in the second and the comprehensible dialogue in the third allow for more dialectical play, enabling Arnold to exploit various registers of discomfort. But someone who can identify the movie used in Piece touchée and can’t recognize Gregory Peck or To Kill a Mockingbird in Passage à l’acte may well assess these films differently.

The few critical commentaries I’ve read about Arnold’s trilogy imply that he’s doing something psychoanalytical. For instance, a blurb from the San Francisco Cinematheque states that the trilogy’s targets are “the conventions of Hollywood filmmaking and its inherent repressions.” This suggests that Arnold’s manipulations bring the repressed to light — exposing, as it were, the “unconscious” of the Andy Hardy movies.

The problem is that Freud’s theory of the unconscious refers to the minds of individuals — not to movies, which don’t have minds. And if we bring in Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious, we have to establish what collectives we’re thinking of. Do we mean all the people who made creative contributions to the Andy Hardy movies, all the people in the audience who saw the originals, or some combination of the two?

I think we have to opt for the third possibility — and in the case of Alone also consider the audience of Arnold’s film, which includes many people like me who don’t know the Hardy movies. And despite the differences among these groups, I think we can safely assume there’s a lot of shared cultural baggage. Robert B. Ray in his 1995 book The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy notes that while practically nothing analytical has been written about these extremely popular movies, “they continue to be mentioned…as the principal source of television’s sitcoms (from Ozzie and Harriet and Father Knows Best, the series most obviously derived from the Hardy series, to Family Ties and The Cosby Show).” Which is another way of saying that we all know these movies indirectly, probably at several removes.

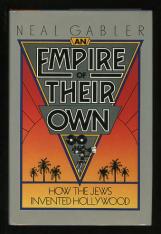

Neal Gabler in his persuasive 1988 book An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (which offers a much better argument than the oversimplified 1997 TV documentary based on it, Hollywoodism: Jews, Movies and the American Dream) suggests that the Hardy films can be seen as the propagandistic version of the American dream that evolved out of MGM studio chief Louis B. Mayer’s denial of his European Jewish roots. Gabler cites Billy Wilder’s recollection of a scene at MGM while he was scripting Ninotchka: “‘We looked out the window because there was screaming going on, and Louis B. Mayer held Mickey Rooney by the lapel. He says, ‘You’re Andy Hardy! You’re the United States! You’re the Stars and Stripes. Behave yourself! You’re a symbol!'”

Does Alone unpack the dark underside of that symbol? To some extent I think it does, even though I don’t immediately see European Judaism on the surface of Arnold’s nightmarish film. Or maybe I do and don’t recognize it, sharing a certain denial with Louis B. Mayer. Shortly after we see Andy and his mom committing incest in the kitchen, we see Andy suddenly slapped by his father, Judge Hardy, who simultaneously yells at him in fury, “Shut up!” It’s a genuinely shocking moment, in part because Arnold has isolated the sound of that explosion so that it erupts from total silence. Arnold then lingers over Andy briefly touching his cheek and slowly registering pain, disbelief, and shame — before replaying Judge Hardy’s slap and command twice again, this time allowing Andy a short verbal response after his pain, disbelief, and shame register: “All right.” In the final replay he follows this with “Dad.”

Is Jewish patriarchal rage rearing its ugly head in an Andy Hardy movie, courtesy of Arnold’s analytical editing? Perhaps, but on the other hand I can’t even be sure that the white-haired man slapping Andy in the chops is Judge Hardy, because he doesn’t seem to resemble the images of that character reproduced in Ray’s book. So Arnold’s extract could be turning another character into a father figure, according him a mythic function he might not have had in the original movie.

Whatever the details of Arnold’s project, he’s certainly transforming a key image of American paradise from our past into a very bad dream. In Arnold’s archetypal Hollywood small town, lovers kiss repeatedly in a park, then start hissing and emitting ducklike wheezes. This is a blighted cosmos where Judy Garland sings “alone” first like a melancholy foghorn and then as if someone has just stepped on her foot — and where a door repeatedly opens and closes as if attacked by some poltergeist until Mickey Rooney finally enters in a top hat and tails and gets stuck in a perpetual dance shuffle, caught in an endless loop that makes us realize he’s actually in hell.