From the Chicago Reader (June 19, 1998). — J.R.

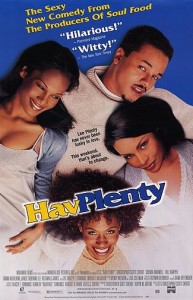

Hav Plenty

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Christopher Scott Cherot

With Chenoa Maxwell, Cherot, Tammi Catherine Jones, Robinne Lee, and Reginald James.

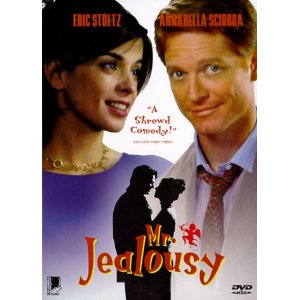

Mr. Jealousy

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Noah Baumbach

With Eric Stoltz, Annabella Sciorra, Chris Eigeman, Carlos Jacott, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Brian Kerwin, Peter Bogdanovich, and Bridget Fonda.

Two eclectic, youthful, and surprisingly upbeat romantic comedies open this week, both by writer-directors; both about blocked novelists, relationships, fear of commitment, jealousy, self-torturing neurosis, betrayal, and ultimate fulfillment; and both set in upscale, urban east-coast milieus. I had a good time at Christopher Scott Cherot’s Hav Plenty and Noah Baumbach’s Mr. Jealousy both times I saw them, though I couldn’t believe in either all the way through, and neither made me laugh out loud very often. Presented as hand-crafted self-portraits that have agreed to play by certain commercial rules and genre conventions, both teem with eccentric tics and personal energies, giving us the pleasure of contact with an individual intelligence — something that seldom happens with bigger-budget fare.

The eccentric tics in Hav Plenty begin with the title — which conflates the first name of heroine Havilland Savage (Chenoa Maxwell) and the last name of hero Lee Plenty (Cherot) — and include Philippians 4:12 (“I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want”); the periodic sound of amplified heartbeats and perhaps thunder; a series of sudden and seemingly unmotivated pratfalls; Plenty addressing occasional asides to the camera and viewer; and a plot that’s doggedly anticliche, flouting every expectation. These and other peculiarities continually caught me off guard — which is why I often found the movie amusing.

A homeless novelist (Plenty) house-sitting in New York for his wealthy former college chum Hav while she spends the New Year weekend with her family in Washington, D.C., is invited to drive down and join her. (Hav is engaged to a famous rap artist who neglects her, spends time with other women, and has other plans for the weekend.) Plenty arrives in time for a small New Year’s Eve get-together. Over the next day Hav’s best friend, Caroline (Tammi Katherine Jones), her unhappy newlywed half-sister, Leigh (Robinne Lee), and finally Hav herself come on to him, but he coolly rejects the advances of all three. (An early title and some of Plenty’s asides assure us that this is “a true story.”) Plenty and Hav drive back to New York, and a year later we see him attending a preview of his first feature as a writer-director — a movie depicting the events of that weekend — and doing an interview after the screening, then landing a distributor.

It’s incidental to all of the above that the characters in Hav Plenty are black; if memory serves, the first white person to appear in the film is the young man who introduces Plenty to the racially mixed audience after the screening in the final sequence. In fact, one thing that makes Hav Plenty fresh is the absence of overt attention paid to the characters’ blackness; the class difference between Plenty and everyone else is more of an issue than the racial or cultural background of anyone. And Plenty, a passive and emotionally evasive intellectual without much glamour and only a modicum of wit, is an unlikely romantic hero, which only adds to the sense that the movie is proceeding by countercliche — even if it still winds up honoring the broader conventions of romantic comedy. Reportedly shot on a $30,000 budget, Hav Plenty shows signs of austerity, and its originality doesn’t always rule out awkwardness. But it manages to tell us more about its varied cast of characters than most romantic comedies costing a hundred times as much.

The eccentric tics of Mr. Jealousy are more smoothly articulated, perhaps because they’re more grounded in a specific movie tradition — the West Village-Soho world of art cinemas, brownstones, warehouses, and luncheonettes recognizable from Woody Allen comedies. (A key image from this world: couples walking down lower Broadway and gesticulating wildly as they discuss the classic or foreign movie they just saw.) Noah Baumbach evoked some of the urbanity and self-consciousness of that milieu in his first feature, Kicking and Screaming, about four college graduates stumped about what to do with their lives. This time he alludes to the art-cinema context much more directly by opening with music from Francois Truffaut’s Jules and Jim and evoking the form of that film with offscreen narration (delivered by Baumbach himself) recounting the story in past tense and with old-fashioned devices such as irises and wipes and French New Wave devices such as fantasy inserts, fleeting flashbacks, freeze-frames, and jump cuts.

It all makes for a lively, graceful surface while Baumbach recounts the first date of 15-year-old Lester Grimm and its traumatic aftermath: he takes a girl to Jean Renoir’s Rules of the Game and to dinner at an Italian restaurant, doesn’t screw up the nerve to kiss her when he sees her home, then briefly spies her kissing a 24-year-old at a party a few weeks later. As in The Magnificent Ambersons — another of Baumbach’s movie models that has an impersonal narrator — the seeds of the story are planted in the opening moments: we’re told that Lester (played as an adult by Eric Stoltz) becomes obsessed with the previous sex lives of all his subsequent girlfriends.

Then the story leaps forward about 15 years to when he’s introduced to Ramona Ray (Annabella Sciorra), a tour guide at the Brooklyn Museum and a graduate student in art history at Columbia University, and they start having an affair. We eventually learn that Lester works as a high school substitute teacher — it’s characteristic of the chummy, upscale narrowness of Baumbach’s world that details such as what people do for a living usually aren’t accorded much importance. (Writer-director Whit Stillman deals with a similar world and uses some of the same actors, but he’s considerably more attentive to class issues.) More significant in the long run is the fact that Lester gets accepted into the University of Iowa’s graduate writing program but decides to ignore this option for a while. By the time he becomes a fiction writer late in the picture, it’s implied that his jealous scenarios with Ramona and earlier girlfriends function as a kind of substitute for writing — or perhaps vice versa.

The story of Mr. Jealousy begins in earnest when Lester, obsessed with a novelist named Dashiell Frank (Chris Eigeman) who used to be involved with Ramona, spots Dashiell entering a building in the West Village and discovers that he attends group-therapy sessions there, presided over by one Dr. Poke (Peter Bogdanovich). Eager to learn more about Dashiell’s past with Ramona, Lester joins the group, posing as his friend Vince (Carlos Jacott) — all of which he conceals from Ramona. (Vince, who can’t afford therapy, tries to benefit from Lester’s experiences when he reports on the sessions at their luncheonette hangout — until Vince joins the group himself, playing Lester with an English accent.) After a bit of sparring between Dashiell and Lester, the two men become friends, and one of the novelistic pleasures of this film is the way we get to know Dashiell first through Lester’s feverish imagination and then, much more gradually, on his own terms, at the group sessions and when Lester visits Dashiell and his stuttering girlfriend (Bridget Fonda) at his apartment. This is Eigeman’s most interesting and layered performance to date, and one of the things that makes it so nuanced is that both Lester and Dashiell are fiction writers who tend to reposition themselves in their work, so that their personas keep fluctuating — the same sort of process examined, albeit more superficially, in Woody Allen’s Deconstructing Harry.

One of the limitations of Mr. Jealousy is that Dashiell proves to be more interesting than Lester, perhaps because the ubiquitous Stoltz projects too wholesome an image to register very convincingly as a troubled spirit. You might say that he plays James Stewart to Eigeman’s John Wayne in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, another key cinematic reference point in Baumbach’s movie. Both Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Mann adroitly brought out Stewart’s neurotic traits, but Baumbach treats Stoltz in a more Fordian fashion.

Nevertheless, Baumbach’s best trait as a filmmaker remains his handling of actors — at least his major actors. (He’s less lucky with the secondary characters in the group-therapy sessions, though that’s probably because these parts are underimagined and underwritten.) Like Renoir and Truffaut, he’s often at his best dealing with the interactions of friends hanging out together and enjoying one another’s company; for edgier, less comfortable moments he might want to learn a lesson or two from the gauche directness of Cherot.