From the Chicago Reader (February 20, 1998). — J.R.

Scotch Tape

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Jack Smith

With Jerry Sims, Ken Jacobs, and Reese Haire.

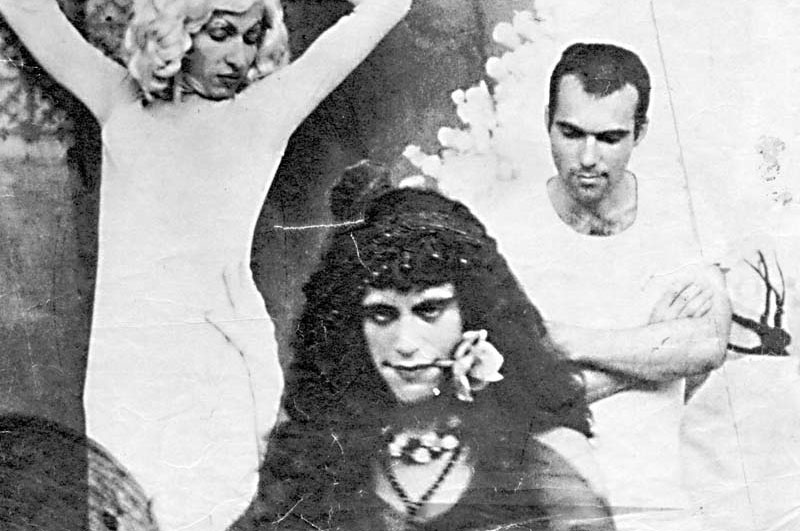

Flaming Creatures

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Jack Smith

With Francis Francine, Sheila Bick, Joel Markman, Judith Malina, Dolores Flores, Marian Zazeela, and Smith.

You’d never imagine this from the mainstream press, but experimental film is on the rise again, as a taste as well as an undertaking — even if it’s often returning in mutated forms like video or in areas of filmmaking where we least expect it. At the Rotterdam International Film Festival three weeks ago, hundreds of Dutch viewers, most of them in their 20s, stormed the largest multiplex in Holland — one of the best-designed facilities I know of, suggesting an unlikely cross between a Borders and a Beaubourg, a mall and an airport — to see work that’s thought to have little or no drawing power in this country. They watched short experimental videos from Berlin, London, and Providence, Rhode Island, at a crowded weekday afternoon program called “City Sounds.” They watched Blue Moon, a charismatic Taiwanese feature by Ko I-cheng whose five reels can be shown in any order (they all feature the same characters and settings, but whether the five plots match up chronologically or as parallel fictional universes — signifying flashbacks, flash-forwards, or variations on a theme — is left to the viewer). They watched several videos by Alexander Sokurov and his most recent feature, Mother and Son. And in a smaller and older Rotterdam multiplex, comparable crowds were turning up for an Ernie Gehr retrospective, Jon Jost’s first video, and experimental documentaries from all over, a few shown with live musical accompaniment. The festival was also screening pictures like Deconstructing Harry and The Ice Storm, but for once these weren’t overpowering the more experimental fare; if anything, the art-house blockbusters seemed relatively marginalized at this event.

Sampling all of the above, I began to think that there are two main trends in experimental work right now, and the chief dividing line between them may be the presence or absence of music. The films and videos with music tend to draw bigger crowds and offer more collective experiences; those without, most of them made by older artists, usually foster a more personal relationship with each viewer. Another way of describing the difference would be to say that the more popular work starts with those elements a young, media-savvy viewer already knows — TV, music, and a built-in skepticism about both media and political change — and the more difficult work chooses a less traveled path, for better and for worse.

Which tradition did Jack Smith (1932-1989) belong to? Surely the first more than the second; yet I’d never ascribe skepticism about political change to his masterpiece, Flaming Creatures — only to some of its explicators and champions.

But we should distinguish between traditions of filmmaking and traditions of film viewing, especially when the social functions of films change over time. Starting Thursday, February 26, the Film Center is presenting four separate Jack Smith programs over three consecutive days, with Flaming Creatures and Ken Jacobs’s Blonde Cobra showing all three days. I’ve seen about five of the seven hours in this retrospective at one time or another, and to my mind the films split quite dramatically between those with sound and music and those comprised of silent footage, not because Smith deliberately divvied up his work that way but because its original functions and settings no longer exist.

Properly speaking, only two integral films by Jack Smith survive: the three-minute color Scotch Tape (1962), showing in the first shorts program, also on Thursday, and the 42-minute black-and-white Flaming Creatures (1963). The remainder is unedited or reedited footage that Smith used in his live performances and footage by others recording his performances, live and otherwise. (Some of this performance footage has been edited into “finished” works like Blonde Cobra and some hasn’t.) Seven years of research and restoration by J. Hoberman (the series curator) and Jerry Tartaglia preceded this program, and one appreciates all the historical and archival decisions involved, but the fact remains that there’s a world of difference between Flaming Creatures and the balance of the program that no amount of goodwill can erase. It’s the difference between one of the greatest and most pleasurable avant-garde movies ever made and large heaps of suggestive or not-so-suggestive supplementary material. And to some extent, moving between these two extremes means partaking of the two trends in experimental filmmaking described above: “musicals” with a social praxis and more arcane objects for individual study.

Implicitly or explicitly, all avant-garde cinema has a dialectical relationship to mainstream cinema, which usually means Hollywood. Apart from Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1939), Flaming Creatures may be the first major avant-garde movie to have embraced Hollywood even as it more implicitly defied its narrative procedures. In this respect it shares a kinship with found-footage films that use mainstream material — a relatively recent tradition stretching all the way from Craig Baldwin to Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinema to a striking Austrian short I saw in Rotterdam, Martin Arnold’s Alone. Love Wastes Andy Hardy. Re-editing fragments of Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland so that they sound like squealing geeks, Arnold clearly subverts his source material, thereby making a “film” rather than a movie. But Flaming Creatures is mesmerizing and luscious partly because Smith is more interested in emulating various features starring Maria Montez or directed by Josef von Sternberg than in subverting them. It’s an act of love, not of revenge.

Historically, the impact of Flaming Creatures in 1963 had less to do with this love than with its presumed sexual content: flaccid penises, bouncing breasts, evocations of an orgy. The object of repeated police raids, it quickly became a cause celebre for free speech in general and “underground cinema” in particular, especially as these were being defined by critic and programmer Jonas Mekas, the film’s most vocal champion at the time. Smith saw the movie strictly as a comedy and eventually became so alienated by Mekas’s rhetorical and institutional appropriation of it that he never made another film that achieved a final form. Fifteen years later, he was calling Mekas “Uncle Fishhook,” and both of his subsequent 16-millimeter features, Normal Love and No President, remained in a kind of performance limbo — the first never finished, the second an assembly of earlier films that was repeatedly reconfigured. (I’ve seen both, nearly three decades apart, and if distant memories are reliable, No President — or at least the February 1969 version I saw — is by far the more interesting of the two.) According to Tartaglia, Smith would re-edit his films even while they were being projected, a practice that D.W. Griffith followed during the initial runs of some of his silent features and that anticipates Ko I-cheng’s strategy of shifting the order of the reels each time Blue Moon is screened at a festival. After losing control over how Flaming Creatures was perceived, Smith restricted himself to controlling the unique shape and direction of each of his performances, which often included footage from other works.

In 1964, a few months before her highly influential “Notes on Camp,” Susan Sontag wrote, “Flaming Creatures is that rare modern work of art: it is about joy and innocence.” Seen today in a more jaded climate, its playfulness exudes sweetness and mystery more than a desire to outrage (which the film also has). Like all of Smith’s work, its basic mode is children’s theater, where dressing up in elaborate drag is the principal pleasure, though a few props — particularly a potted plant and a lantern — are treated every bit as lovingly as the cast and costumes. The movie is shot on a variety of faded film stocks, some of the shots are overexposed, and the resulting textures are so dreamlike that they perform a wondrous kind of alchemy on the action; I can’t think of another cinematic object in which “bad” photography looks more exquisite. Smith modestly credits himself only for this handheld photography in the movie itself, and there’s no question that it’s his brush creating the painterly splendors that unfold, even when he’s jiggling and bouncing the camera to simulate an earthquake toward the end or, more generally, to express his delirious pleasure in what he’s filming.

The idea of brandishing technical imperfection with pride is already present in Scotch Tape, accounting in this case for the film’s very title. Shot in 1959, the film grew out of one of the many shooting sessions organized for Ken Jacobs’s still-unfinished [in 1988] Star Spangled to Death, an epic compilation of found footage interspersed with interludes of Smith’s clowning. On that particular day, Jacobs brought Smith and a couple of his costumed associates, Jerry Sims and Reese Haire, to a demolished building on a stretch of Manhattan’s west side where the Lincoln Center complex now stands, and Smith borrowed Jacobs’s camera to film him and the others dancing among the rusted cables and broken concrete slabs — which in certain shots become more prominent than the people — doing all his editing in-camera. Afterward Smith discovered that a dirty piece of cellophane tape had gotten stuck in the camera gate and wound up getting printed in the upper right corner of every frame; rather than accept this as an encumbrance, he preferred to celebrate its presence in his title. As P. Adams Sitney points out, the tape’s “fixed position offers a formal counterbalance to the play of scales upon which the shot changes are based” — a textbook illustration of what Orson Welles was talking about when he said that a film director is someone who “presides over accidents.”

Three years later Smith asked future filmmaker Tony Conrad to edit the Scotch Tape footage to match a Peter Duchin rumba, and Conrad described the results as a personal epiphany: “All of a sudden, a commitment emerged, a kind of special pleasure that reached out and grabbed the whole scene in a way that was inhabited by a very, very special comic presence. It was on the way to ecstasy; in fact it was ecstasy. And at that point, I was won over to be a filmmaker; it was such an extraordinary thing to see, what happened to sound in the presence of a moving image.”

Most of Flaming Creatures is an elaboration and extension of the ecstasy described by Conrad, this time to the strains of such varied materials as “Amapola” (a 30s rumba subtitled “Pretty Little Poppy”), a mock radio commercial with hokey music for a “new heart-shaped lipstick [that] shapes your lips as you color them,” Yoshiko Yamiguchi performing “China Nights” (the title song of a 1940 Japanese movie), Bela Bartok’s Concerto for Solo Violin, Kitty Wells singing “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” a 1930s Cuban bolero called “Siboney,” and the Everly Brothers’ version of “Be-Bop-a-Lula.” And what transpires beneath this musical material is mainly a group grope of cascading and overlapping semicostumed men and women, filmed in various kinds of shallow space and overflowing the various compositions. Sometimes these writhing bodies are seen from a ladder looking down, sometimes from closer proximities; often they’re viewed from tilted angles that confound our overall sense of an integral space. The narrative continuities may get confused, but the shots themselves are visionary marvels, stunning in their generosity and at times evoking tableaux from the late films of Sergei Paradjanov, which often suggest densely packed jewel boxes.

The ghosts of Hollywood features like Cobra Woman, The Devil Is a Woman, and The Shanghai Gesture hover over the action of Flaming Creatures, not only in its exotic accoutrements and low-rent dreams of opulence, but also in its manner of announcing itself, specifically its opening and closing titles, which simultaneously mock and celebrate its Hollywood inspirations. The florid title card makes a delayed appearance, and the cast list, which turns up a limp penis or two later, is initially obscured by the silhouettes of a woman and a man with a flower. Eventually these shadows move away, but even when the cast list can be seen without encumbrance, it remains only semilegible. Similarly, near the end of the film “The End” appears in fancy script between a pair of bare legs and hangs on afterward like a dogged prop, another item in the film’s crowded agenda of crisscrossing limbs and organs. Like the blond drag queen who turns up just before, periodically smoking a cigarette while she’s being ravished, it’s a simple and comic acknowledgment that even the most important elements in a psychosexual scenario often turn out to be mere distractions when other factors supersede them.

Smith wrote two major critical-theoretical position papers, “The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez” and the much shorter “Belated Appreciation of V.S.” (meaning von Sternberg); published in Film Culture around the time of Flaming Creatures, they throw a certain amount of light on his sources. (They’ve recently become available again in Wait for Me at the Bottom of the Pool: The Writings of Jack Smith, a well-documented collection edited for High Risk Books by Hoberman and Edward Leffingwell.) Both have been called camp manifestos written before camp taste entered the mainstream, but they’re even more relevant as passionate personal declarations that outline some of the psychic determinants behind Smith’s image pool. In her early defense of Flaming Creatures, Sontag rightly termed it more intersexual than homosexual and related it mainly to pop art and “the poetic cinema of shock” rather than camp; other commentators have noted it as a crucial forerunner of many avant-garde theater productions staged by Robert Wilson (such as Deafman’s Glance) and Richard Foreman.

All these ideas are pertinent to placing this gorgeous eruption in a historical context, but I’m not sure they explain why the movie plays so well today, in every sense of the word. And whether Smith was a paranoid madman, as some people have claimed, or a perfectly lucid anarchist who didn’t like the way his comedy was turned into a political and aesthetic banner for others might not matter either. I interviewed Mekas in 1982 for a book-length survey of independent and experimental filmmaking, and in spite of his own role in politicizing Flaming Creatures, he adamantly insisted that Smith’s work had nothing to do with protest or politics: “Later, once it was shown, it became political. But the creation of it did not come from any political necessity.”

I disagree now as much as I did then, but I have to concede that all visionary art tends to have a problematical relationship to politics. For all its boisterous comedy — and in part because of it — Flaming Creatures offers itself as a vision of paradise, but it posits paradise as something already attained rather than as a goal that characters might strive to achieve. How to get there isn’t really Smith’s agenda; his achievement as an experimental filmmaker is to take you somewhere you’ve never been before and to leave you there for a spell. And his instinct as an entertainer is to orchestrate this paradise with music, creating a common bond of recognition that ever so slightly suggests such a paradise is within the grasp of everyone.