Since writing this for the April 27, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader, I’ve become an even bigger fan of Charles Willeford’s four Hoke Moseley novels; some of their virtues remind me of John Updike’s novels about Rabbit Angstrom. My favorite of these Moseley novels remains Sideswipe. — J.R.

MIAMI BLUES

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by George Armitage

With Fred Ward, Alec Baldwin, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Nora Dunn, Charles Napier, Obba Babatunde, and Shirley Stoler.

Q&A

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Sidney Lumet

With Nick Nolte, Timothy Hutton, Armand Assante, Patrick O’Neal, Lee Richardson, Luis Guzman, Charles Dutton, Jenny Lumet, and Paul Calderon.

The ambiguous power and image of the policeman stand at the center of two better-than-average crime pictures playing at the moment, both of them the work of writer-directors adapting novels by others. Part of the merit of these two otherwise very different movies is that neither one depends on either of the compulsively overworked subgenres that currently dominate the scene — the cop-buddy action thriller derived from TV or the hunt for the serial killer derived from Dirty Harry.

I have less of an aversion to the cop-movie genre per se than to what this genre has become. Both subgenres cited above have tended to support the law-and-order social agenda promulgated by Reagan and Bush, which presents cops not merely as the defenders of the law, but also as the upholders of the status quo and the only thing standing between middle-class tranquility and chaos. They may not always be impeccable law abiders themselves, but their own imperfections are generally viewed as secondary to the necessary and honorable tasks they perform, which usually amount to “wiping out scum.” In effect, the knightly credo of Philip Marlowe and certain other private gumshoes has become the rallying cry of the movie cop — “It’s a dirty job, but someone’s got to do it” — except that now the “dirty job” isn’t so much ferreting out the truth as it is blowing the heads off serial killers and drug dealers. (There are some acute remarks about this trend in Thomas Pynchon’s new novel, Vineland.)

This isn’t to say that Miami Blues and Q&A don’t belong to recognizable crime-and-cop subgenres of their own; it’s just that these subgenres are a bit more specialized, which means that both movies come across as relatively fresh and unpredictable. Even more to the point, both writer-directors give their material a personal stamp; they both seem to care a lot about details; one never is made to feel that they’re merely going through the motions of a routine assignment. Both movies have their share of violence, and both function pretty well as thrillers, but their separate takes on what being a cop means give the films their focus and interest.

With Q&A Sidney Lumet takes a solo screenwriting credit for the first time in 33 years of directing — a move that only helps to confirm that, contrary to his largely negative reputation in auteurist circles, he deserves to be treated as an auteur in his own right. Indeed, the subgenre that Q&A belongs to is largely one of Lumet’s own making.

In the 60s, in his highly influential book The American Cinema, Andrew Sarris cordoned Lumet off with several other liberal directors under the category of “Strained Seriousness” (“At his best, Lumet’s direction is efficiently vehicular but pleasantly impersonal”). At that point Lumet was mainly known for his liberal-humanist sentiments (a pejorative association for most auteurists that linked Lumet to such stylistic nullities as Fred Zinnemann and Stanley Kramer) and as an adapter — of Tennessee Williams (The Fugitive Kind), Arthur Miller (A View From the Bridge), Eugene O’Neill (Long Day’s Journey Into Night), and Anton Chekhov (The Sea Gull); his other projects seemed much too scattered and varied to suggest much stylistic or thematic consistency.

Admittedly, Lumet continued to take on a bewilderingly wide array of assignments during the 70s and 80s, and the quality of his films varied just as widely. But a distinctive feeling for New York that was already apparent in 12 Angry Men, The Pawnbroker, and Bye Bye Braverman became increasingly evident in Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, Prince of the City, Daniel, and Garbo Talks; even The Verdict, set in Boston, and Running on Empty, set in small towns, added to a sense of what was becoming distinctive about Lumet’s work. A liberal’s anguish about the corruption pervading the country’s legal and judicial systems (and police corruption in particular in Serpico and Prince of the City); a Manichaean, quasi-tragic sense of evil power structures and defeated idealists; a warm, observant, and often humorous eye and ear for the ethnic, racial, and sexual diversity of New York; and a continuing curiosity about how this diversity both affects and inflects the way the city is run. Some of this may still qualify on occasion as “strained seriousness,” but at least it is a form of strained seriousness that is distinctively Lumetian.

For better and for worse, all of these characteristics are on full display in Q&A, based on a novel by the New York state supreme court judge Edwin Torres, which follows the efforts of Al Reilly (Timothy Hutton), an earnest assistant district attorney, to expose a killing committed by crooked cop Mike Brennan (Nick Nolte) in Spanish Harlem as less-than-justifiable homicide. It’s entirely to Lumet’s credit that though the film has a running time of 134 minutes it never seems sluggish or padded, largely because his grasp of various interlocking New York milieus — the police force, the city government, the Latino crime underworld, and the world of transsexual prostitution — is so finely detailed. What’s less convincing is Lumet’s overall sense of good and evil, at least when it comes to depicting his hero (Reilly) and villains (Brennan and homicide bureau chief Kevin Quinn, played by Patrick O’Neal) — none of whom are a fraction as lively or as interesting as the characters surrounding them.

It was easier for Lumet to deal with comparable Manichaean extremes in The Verdict because that film’s visual style of Rembrandtesque gloom — as well as the iconic force of Paul Newman as a fallen angel struggling to regain his honor and ethics — made such conceits more palatable. Here, though the cinematographer, Andrzej Bartkowiak, is the same, the visual style is more naturalistic. And while the hero is once again depicted in the script as a flawed individual heroically struggling to clean up his act — he lost his true love Nancy (played by Jenny Lumet, daughter of Sidney and granddaughter of Lena Horne) because of his own submerged and unconscious racism — the casting of Timothy Hutton tends to undermine this premise iconographically as well as dramatically. As in Daniel, Hutton is such an innocent, suffering liberal that when we learn of his earlier, unseen transgression — recoiling when he discovered that Nancy’s father was black — it just doesn’t seem believable. (When John Cassavetes dealt with a similar existential crisis in his first feature, Shadows, he made the moment both real and consequential by showing it happen; Lumet’s script, by merely alluding to it as a distant memory, can only pose it as theoretical.) By the same token, Brennan and Quinn, as scripted and played, are too purely and uncomplicatedly evil to be very interesting as characters.

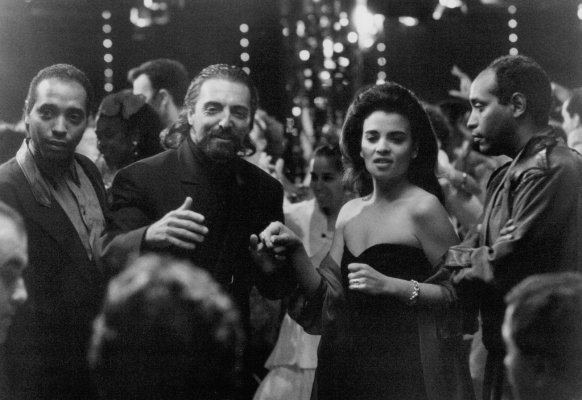

Reilly encounters Nancy Bosch again as the mistress of Bobby Texador (Armand Assante) — a rather charismatic Latino gangster who witnessed the killing committed by Brennan. Texador is accompanied by Nancy, two other witnesses, and a shady Jewish lawyer when he is called in for questioning; Reilly’s two associates at the interrogation, Luis (Luis Guzman) and Sam (Charles Dutton), are Puerto Rican and black, and Lumet’s handling of this extended sequence, which pivots around both Reilly’s unexpected rediscovery of Nancy and the diverse racial, ethnic, and sexual tensions among the eight characters, is one of the most remarkable achievements of his career. Although nothing else in the film reaches quite the same level of effectiveness, it’s a scene that graphically illustrates the movie’s basic theme — that racial and ethnic tensions have a lot to do with how a city operates, regardless of whether or not the people involved are aware of them — and most of the remainder of the film is devoted to elucidating this concept.

If the movie’s conclusion seems defeatist to a fault, this may have something to do with the masochistic side of Lumet’s liberalism, a trait that has been fully present in his work at least since The Pawnbroker. While the film can certainly be credited with transcending the complacencies of more conventional cop movies, it isn’t enough simply to turn the genre on its head — by demonstrating that its Dirty Harry type is actually a racist and homophobic closet queen, that its Latino drug dealer has his good side, or that its clean-cut hero is tainted along with everyone else. But at least it’s an improvement as a working model.

***

I haven’t seen George Armitage’s previous features — which include Private Duty Nurses, Hit Man, Vigilante Force, and Hot Rod — but it’s clear that the subgenre that Miami Blues belongs to is not of Armitage’s own making. It can be roughly defined as the low-budget “criminal on the run in a big city” film that was also the source of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless in 1959. Godard placed a good deal of importance on the criminal’s doomed romance during his flight from the law, and his extraordinary stars, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, did so much with and for their parts — as the flamboyant, nihilist hood and his innocent yet ultimately betraying lover — that this subgenre took on a slightly different profile after they were through with it. It is to the post-Breathless form of this subgenre that Miami Blues owes its allegiance.

The project originally took shape when actor Fred Ward optioned Charles Willeford’s novel Miami Blues and sent the book to director Jonathan Demme, with whom Ward had worked on Swing Shift. Demme, in turn, sent the novel to Armitage, and wound up as the film’s coproducer, while Ward took on the part of Hoke Moseley, the novel’s gritty police detective. (Willeford, a skillful pulp writer who died last year with about two dozen books to his credit, adapted his own novel Cockfighter for Monte Hellman’s memorable 1974 film; he wrote four Hoke Moseley novels during the 80s, and Miami Blues was the first. I’m currently reading the second, New Hope for the Dead, and what’s most impressive so far is how well Willeford knows his milieu; he’s like the John O’Hara of Miami in the 80s.)

Miami Blues has been getting a lot of favorable reviews, although many reviewers have been qualifying their praise, insisting there’s nothing “profound” about the movie (words like “lightweight,” “disposable,” and “nonserious” have been cropping up with some regularity). Although I wouldn’t entirely dispute this — commercial movies haven’t been exactly rich in profundity lately — I still think it’s worth pondering why so many reviewers are going out of their way to make this point, especially when they don’t generally bother to make the same point about more routine crime pictures. The implication is that “profound” movies — like, say, Driving Miss Daisy — deal with a better class of people. (It seems that the same sort of unstated bias led many reviewers to be dismissive of Car Wash and D.C. Cab several years ago, using terms like “junk food” that are now being applied to Miami Blues.) Certainly the predilection of Jonathan Demme for various styles of lower-middle-class glitz and Armitage’s emphasis on gore in a couple of the action sequences conspire to make the taste of these two former Roger Corman employees somewhat disreputable in an upscale art-house context, but I can’t see what any of this has to do with seriousness or the lack of it.

Like Belmondo in Breathless, Junior Frenger (Alec Baldwin) is a free-wheeling crook whose stylish chutzpah as a criminal and his tendency to invent his own identity as he proceeds are more matters of improvised play than of careful deliberation; unlike the Belmondo character, though, he is something of a borderline psycho who intermittently seems to believe some of his own lies. When he steps off the plane in Miami at the start of the picture, he steals a woman’s suitcase, and then later throws a pesky Hare Krishna to the floor. Somewhat later –after Junior has checked into a fancy hotel with a stolen credit card and ordered a hooker from the bellboy — we learn that he actually broke a finger of the Hare Krishna, who died of shock, and Hoke Moseley is already on his case.

Junior’s crime is every bit as gratuitous (if more inadvertent) as Belmondo’s killing of a cop at the beginning of Breathless, and the detective who tracks him down for the remainder of the picture is much more prominent than Daniel Boulanger’s Inspector Vital in Godard’s film (although he’s just as sleazy and methodical). The point isn’t that Miami Blues is consistently modeled after Breathless, but that the use of these loose archetypes and situations allows Miami Blues to pursue its own lively existential jaunt, which has a lot more to do with cops and what they signify than Godard’s movie.

Most of Junior’s subsequent criminal exploits consist of him impersonating Moseley — holding up criminals and making off with their stolen goods or money by using Moseley’s own badge and revolver — and his behavior often suggests that he’s more interested in the childish pleasure of playing cop than he is in the actual thefts. (Maybe it would be more precise to say that the roles of thief and cop become merged in his head, so that he can’t always tell them apart.) Junior’s glamorous, grandstanding fantasy about being someone like Moseley is contrasted throughout with the total unglamorousness of Moseley himself. It’s an ambiguity that the whole movie is structured around, and has a lot to do with what gives the movie its punch — suggesting that what “cop” means to this ex-con is just as mythical as what “criminal” means to a cop like Brennan in Q&A. For my money, this is just as serious and as provocative as the friendship between an old lady and her chauffeur.

The hooker (Jennifer Jason Leigh) ordered by Junior calls herself Pepper, but before long Junior has extracted her real name, Susie Waggoner, and gotten her to try on one of the fancy dresses in the stolen suitcase (he claims they belong to the wife he says he’s just left). A naive, good-natured country girl who’s working her way through college, she quickly warms to Junior’s style and falls for him without realizing that he’s a crook and an ex-con. Later in the day he meets Susie again in a restaurant, and by this time they’re a full-fledged romantic couple. He moves into her apartment, gets her to cash in her $10,000 certificate of deposit, and helps her write a haiku for her English class (a very Demme-like detail).

Moseley tracks Junior down through his link with Susie, and winds up getting himself invited to dinner with the two of them. He has the rather disgusting habit of periodically taking out his loose dentures, and when Junior turns up at Moseley’s crummy hotel room the next day to beat him up and steal his gear, he makes a point of swiping Moseley’s dentures as well, just for spite — although he curiously leaves Moseley $80 as a token payment, a gesture that the film never satisfactorily accounts for. (It’s mainly the badge and gun that signify “cop” to Junior, but, as we gradually learn, it’s the dentures that matter most in spelling out Moseley’s identity; in classic doppelganger fashion, Moseley’s subsequent search for Junior is partially a quest to regain his dentures and with them his identity.)

Part of what makes Miami Blues so good is its perfectly controlled balance between the parts of the story focused on Junior and Moseley, each of which has a very different kind of wry humor, beautifully and economically spelled out by Armitage’s direction. (Moseley has no girlfriend of his own, but he is eventually teamed up with a Cuban cop named Ellita Sanchez — played by Nora Dunn — whose cool respectability rubs against his grittiness with as much friction as that produced by Susie’s domesticity and Junior’s restlessness.) Another part of what’s so good is the performances of the three leads; each one is perfectly measured and proportioned in relation to the film’s overall design, never sticking out or detracting from the others. (Baldwin has been getting most of the media attention, but Ward and Leigh are every bit as fine.) The whole movie is framed by the effective use of a pop single, Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit in the Sky,” over the opening and closing credits, and the balance of elements between these two points lives up to the bookend symmetry.

One should also take note of this movie’s acute sense of place — which is every bit as confident as Lumet’s feeling for New York, and which even extends to the recounting of a couple of southern Florida recipes. (I suspect that Willeford’s novel has a lot to do with this, although the fact that Demme grew up in Miami undoubtedly helps.) The choice use of locations — shot by Tak Fujimoto with a nice feeling for light and ambience — gives some of the places that are used as much flavor as the characters. I’ve never been to Miami, but I strongly suspect that Miami Blues has more to tell me about that city than Driving Miss Daisy has to say — to me or anybody else — about Atlanta.