Here are ten of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1990 / Close Up – The motorcycle ride of Makhmalbaf and Sabzian.

Iran. Director: Abbas Kiarostami. Cast: Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Hossein Sabzian. Original title: Nema-ye Nazdi.

Why It’s Key: A convicted imposter finally meets the man he’s been impersonating, and they set off together to visit the family that was fooled.

Hossein Babzian, a bookbinder, emerges from a jail sentence for having impersonated famous filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to ingratiate himself with the well-to-do Ahankhah family, pretending he was planning a movie about them. He’s greeted by the real Makhmalbaf, arriving on his motorbike to take him to visit the Ahankhahs, and filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami and his crew, who have arranged this meeting, are filming the entire encounter from a distance. We hear them saying that Makhmalbaf’s lapel mike is faulty, and notice that the dialogue between Makhmalbaf and Sabzian (“Do you prefer being Makhmalbaf or being Sabzian? I’m tired of being me”) periodically becomes inaudible — on the street, after Sabzian climbson the back of the motorbike, and when they stop briefly for Sabzian to buy flowers for the Ahankhans.

But is this faulty sound the truth, a half-truth, or an outright lie? Is it an accident or a contrivance? What we’ve previously seen in this film has been a restaging of events, including the trial, by all the participants. And the sound was deliberately and overtly suppressed during part of the final sequence in Kiarostami previous “non-fiction” feature, Homework (1988). During the latter part of the motorbike ride here, we hear no dialogue at all, but a very effective reprise of the theme music from Kiarostami’s very first feature, The Traveler (1974), suggesting that this apparent accident is very helpful to Kiarostami’s dramaturgy. Is it possible, then, that he is himself guilty here of impersonating a documentary filmmaker?

***

Scene

2003 / Crimson Gold – The hero jumping into the millionaire’s swimming pool.

Iran. Director: Jafar Panahi. Cast: Hussein Emadeddin.

Original title: Talaye sorkh.

Why It’s Key: A pizza delivery driver who’s always made to feel out of place tries to go with the flow.

The action of Jafar Panahi’s fourth feature —- the second one to have been scripted by his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, who based the story on a true incident —- is bracketed by a pizza delivery man’s pathetic, abortive efforts to hold up a jewelry store. And the night before this happens, at the end of a long day full of everyday humiliations, Hussein delivers a pizza to a millionaire in a swank penthouse whose female companion has just walked out on him. The neurotic and talkative rich man invites Hussein to share his pizza with him, and it’s the only time in the movie when we see the hero relaxing. He spends the remainder of the evening wandering around the palatial digs, supposedly like a kid in a candy store. But Hussein is played by a nonprofessional actor — an overweight, medicated paranoid schizophrenic —- and his deadpan responses to his surroundings are never more incongruous than when he spontaneously dives, fully dressed, into the millionaire’s indoor pool.

Should we conclude that Hussein’s seeming idyll in the penthouse partially motivates his criminal behavior the next morning by showing him what he can’t have? The film won’t say, though perhaps we could conclude that the rich man’s friendliness only underlines the impossibility of Hussein’s ever joining any class above his own. The film takes care not to motivate him with any facile psychologizing, yet the diffidence of the actor’s performance offers a glancing clue that he can’t even be convincingly carefree when he wants to break loose.

***

Film

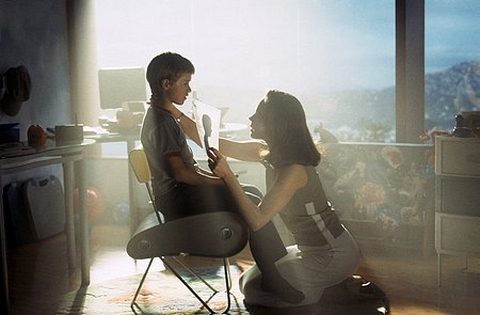

2001 / A.I. Artificial Intelligence – The last day the robot hero spends with his mother.

U.S. Director: Steven Spielberg. Actors: Haley Joel Osment, Frances O’Connor.

Why it’s Key: Humanity ends with a screwed-up android spending an idyllic day with the clone of his adopted mother and then going to bed with her.

The last major film project of Stanley Kubrick, realized posthumously by his friend Steven Spielberg, can easily be read as an allegory about cinema that also becomes a parable about the delusions of mankind. A boy robot named David has been programmed to love Monica, his adopted mother, even after she abandons him, believing that she’ll reciprocate his love if, like Pinocchio, he becomes a “real boy”. Many centuries after mankind has perished, David is found by future beings who intercept his memories and tell him that they can resurrect both Monica (using a preserved lock of her hair to clone her) and the suburban home where she once lived with David, but only for one day, after which she must vanish forever. So they spend a blissful day together, his seventh birthday, and then go to bed together, where he falls asleep for the first and only time, becoming a “real boy” at the same moment that he and Monica and the rest of humanity essentially breathe their last gasp.

The bleakness is quintessential Kubrick, the suburban bliss quintessential Spielberg, and the triumph and desolation of this terminal Oedipal quest seems to belong to the personal visions of both filmmakers. The Blue Fairy who grants David his last wish by giving him his erotic idyll with Monica oddly resurrects both the mysterious black monolith of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and the benign extraterrestrials of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, melding them together into the same ecstatic yet despairing vision.

***

Scene

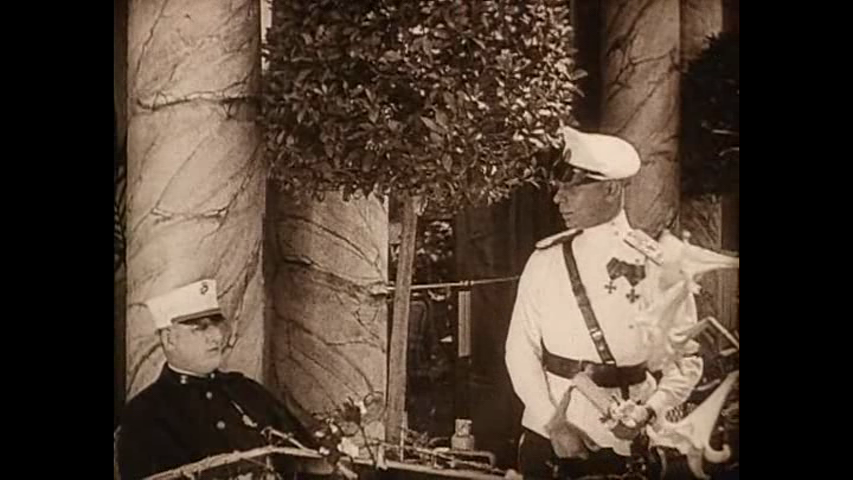

1922 / Foolish Wives – The episode with the armless veteran.

U.S. Director: Eric von Stroheim. Actors: Eric von Stroheim, Miss Dupont [Patsie Hannon], uncredited actor.

Why it’s Key: Stroheim moves from comedy to pity to morbidity as he introduces and brings back a minor character,

We’re in Monte Carlo shortly after the end of World War 1, where veterans on crutches and kids playing soldiers form an essential part of the background. Karamzin (Eric von Stroheim), a counterfeiter pretending to be a Count, dressed to the nines in a military uniform, has been flirting with Mrs. Hughes (Miss Dupont), a wealthy American, on the terrace of a swank hotel. He even bribes a bellboy into paging him in order to impress her. When a stolid man nearby neglects to pick up the book she accidentally drops, we assume that this incidental character is around merely to indicate the kind of courtesy she’s accustomed to receiving, and to provide Karamzin with an opportunity to display his own gallantry by picking up the book and taking it over to her.

The second time this man appears, he neglects to pick up her dropped purse in an elevator, and we imagine him to be some sort of running gag. Then, when we subsequently discover he’s armless from the war, we’re brought up short, made to feel guilty and moved to pity. But as Mrs. Hughes — who feels guilty herself for having leapt to the wrong conclusion — proceeds to fondle and caress one of this veteran’s armless sleeves, pity quickly turns into disquieting morbidity, and what we’ve previously been led to ignore we’re now obliged to dwell upon. In a brief instant that illuminates the rest of the film, comedy turns into tragedy and the tragedy becomes a fetish.

***

Film

1979 / Stalker – The miracle in the final shot.

West Germany/U.S.S.R. Director: Andrei Tarkovsky. Actor: Natasha Abramova.

Why it’s Key: After all hope is lost, a moment of ecstatic revelation.

Few films resist synopsis more than Stalker, but the emotions and the decrepit settings are never in doubt. The story concerns the title hero being hired by a writer and scientist to guide them into the supposedly miraculous Zone, where their innermost wishes are supposed to be fulfilled. But an absence of miracles is all they encounter, and the three men come back beaten, the Stalker most of all. Greeted by his wife and crippled daughter, he declares himself a failure, the world a desolate place devoid of faith.

However reluctant Tarkovsky may have been to discuss the story’s allegorical meanings, he was outspoken about its main theme, “human dignity”, and the redemptive power of love shown by the Stalker’s wife –calling it a “final miracle to set against the unbelief, cynicism, moral vacuum poisoning the modern world” as exemplified by the writer and scientist. But in fact the film concludes with another miracle concerning the daughter.

Seated alone — after reading a poem that we hear her recite in voiceover while dandelion fluff drifts around her — she idly, telekinetically, and rather sadly makes two glasses and a jar slide across the table in front of her as the camera moves back. Then, as the camera moves forward again, the loud rattle of an approaching train is briefly accompanied by Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” before the image fades out on her placid face. The sounds of the train and Beethoven seem equally matched against this quiet, unseen moment of ecstatic revelation.

***

Film

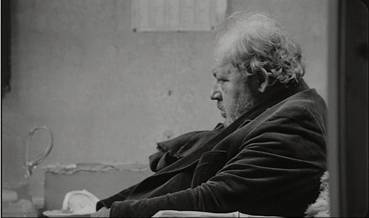

1994 / Satantango – The doctor drinking himself into a stupor.

Hungary/Germany/Switzerland. Director: Béla Tarr. Actor:

Peter Berling. Original title: Sátántangó.

Why it’s Key: In a long, virtuoso sequence where practically nothing happens, we such how much work getting drunk can be.

Around 75 minutes into Satantango — a 450-minute, black and white black comedy set in rural Hungary in which everyone’s a scoundrel, everything is monstrous, and it never stops raining —- the film spends about an hour with a burly doctor, and for most of that time he’s alone. During the first half of this protracted stretch, filmed in very few takes, he’s seated in his shack, drinking himself into a stupor with fruit brandy when he isn’t spying on his neighbors through binoculars, pointlessly recording their precise movements in copious detail in a journal he’s keeping, or snapping at a woman who briefly stops by to deliver his food. We even see him nod off and start snoring at one point, and stumble to the floor and pass out at another. Otherwise he just keeps drinking, pouring out more fruit brandy, and mumbling to himself. Somehow, director Béla Tarr and screenwriter László Krasznahorkai, adapting his own novel, keep us mesmerized throughout this unholy spectacle.

By contrast, the second half of this sequence —- when the doctor runs out of brandy and has to trudge out into the rain and mud to get some more —- is action-packed. Yet what’s so hilarious about the first half, especially as it’s performed by Peter Berling (an actor best known for his work with Rainer Werner Fassbinder), is its demonstration of how much exertion is required simply for this overweight man to get himself drunker and drunker. This project becomes an almost heroic effort, worthy of Samuel Beckett.

***

Scene

1974 / Parade – Two kids playing with circus props after the show is supposedly over.

France/Sweden. Director: Jacques Tati. Actors: Anna-Karin

Dandenell, Juri Jägerstedt.

Why it’s Key: Tati ends his career by asserting that we, not he, are the greatest show on earth.

The final sequence in Jacques Tati’s last and least known feature —- a performance shot mainly on video in Stockholm’s Circus Theatre for Swedish television, but also a passionate manifesto —- is almost four minutes of improvisation by two kids: a three-year-old girl and a six-year-old boy, playing with stage props after the show is over and mainly trying to imitate the professionals they’ve just seen. According to Tati’s biographer David Bellos, these tots, recruited from a nursery, were selected not just for their looks but also because they were the least obedient in following orders. Their restless activities — hitting bells with hammers, painting, trying to juggle with paintbrushes, letting air out of balloons, trying to play musical instruments, and rocking back and forth inside huge bowls —- look strictly unsupervised.

Parade is Tati’s ultimate assertion that ordinary people and spectators can be as interesting and as enlightening to watch as professional entertainers, himself included. (He’s the emcee, and he also performs his most famous pantomimes, but he takes care to show how bored one little girl is when he makes his first appearance.) This is also part of the message of his masterpiece Playtime, but Tati radicalizes the notion even further here by going out into the lobby and focusing on latecomers just as the show’s getting started. And after he focuses on these two kids performing their own show at the end, and doing it strictly for themselves, he pans upward past a couple of adult spectators in the otherwise empty front bleachers.

***

Scene

1943 / The Leopard Man – Teresa walks home at night in a Mexican border town.

U.S. Director: Jacques Tourneur: Actors: Margaret Landry, Kate Lawson.

Why it’s Key: It’s the most terrifying sequence in Val Lewton’s oeuvre.

A five-minute sequence occurring only eight minutes into a 66-minute feature, this sequence terrifies, above all, because of the way it prods our imagination. The story has just strangely shifted focus from a nightclub dancer in a border town — who unwittingly caused a rival’s rented leopard to break loose — to Teresa, a teenage neighbor whose house she passes.

Sent out by her mother to buy corn meal for her father’s tortillas, Teresa doesn’t want to go because of the escaped leopard, but her unsympathetic mother dismisses her fears even after her kid brother teases her about them. Her mother even locks the front door after her, saying she can’t return without the corn meal. But the nearest shop she visits is already closed, so she has to walk across the dark, wind-swept town, dodging tumbleweeds that suddenly sweep past her, to a larger store, where the shopkeeper remembers her as a girl afraid of the dark. Then, on her way home, our dread is stoked by the sound of dripping water and a pair of shining eyes under a railway trestle, then by the sudden scream of a train speeding past, and finally by close-ups of the snarling leopard. She flees, and when we next hear her hammering on the door of her home, pleading for her mother to open it, the lock jams, and we hear rather than see what ensues —- until a trickle of blood appear under the door. Imagining the awfulness rather than seeing it only makes it more upsetting.

***

Speech

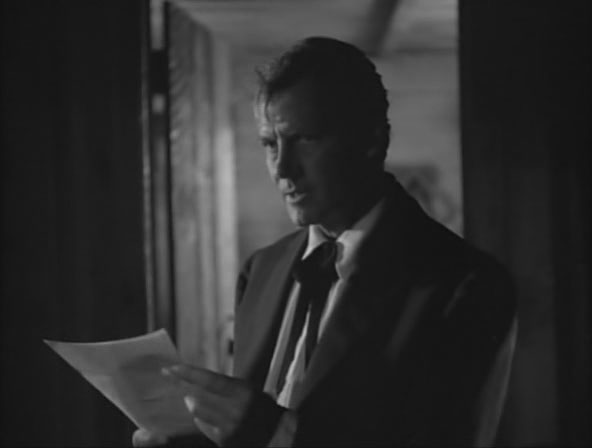

1950 / Stars in My Crown – Josiah Doziah Gray reads the imaginary will of Uncle Famous Prill.

U.S. Director: Jacques Tourneur. Actors: Joel McCrea,

Juan Hernandez, Dean Stockwell.

Why it’s Key: Jacques Tourneur illustrates his credo — that nothing is more powerful than people’s imaginations.

Stars in My Crown was Jacques Tourneur’s favorite among his own films. But he’s commonly viewed as a genre director, and if this uncharacteristic and low-budget MGM item about a small-town parson in the post-bellum South belongs to any recognizable genre, it’s the inspirational religious picture. Yet Tourneur clearly believed in the audience’s imagination and its innate decency more than any religion. And Josiah Doziah Gray (Joel McCrea) pretending to read the imaginary will of Uncle Famous Prill (Juano Hernandez), a black man who refuses to sell his property, to a band of neo-Klansmen with torches preparing to lynch him, is a beautiful illustration of the wisdom underlying both beliefs. What Gray accomplishes in his performance to the masked men he accomplishes with us as well, because we only discover that the will is imaginary at the scene’s end. “You can have him now,” Gray says melodramatically, after reaching the end of Prill’s thoughtful bequeathments to his neighbors — knowing or at least hoping that these reminders of Prill’s generosity and his many links to this community will ultimately save his life, as it does.

“There’s no writing here —- this ain’t no will,” says Gray’s adopted son John (Dean Stockwell), the film’s narrator, when he sees the blank pages on the ground. “Yes it is, Son —- it’s the will of God,” says Gray, which might be taken as a concession to Tourneur’s designated genre. But in fact, it’s the collective will and conscience that Tourneur is speaking to, stirring, and celebrating.

***

Scene

1960 / Shoot the Piano Player – The gangster’s mother dropping dead.

France. Director: François Truffaut. Cast: Richard Kanayan, Claude Mansard, Daniel Boulanger. Original title: Tirez sur la pianiste.

Why It’s Key: Truffaut proves conclusively that you can do anything in a movie.

Like Godard’s Band of Outsiders four years later, Truffaut’s second feature flopped commercially and then became universally cherished, for similar reasons —- a confounding of genre expectations that alternates laughs with shocks in a noirish context with adorable characters. One of the hero’s brothers, a mischievous kid named Fido (Kanayan), gets kidnapped by two childish thugs who proceed to boast to him about their various possessions as they drive him away: Ernest (Daniel Boulanger) brags about his musical lighter (which plays the theme from Lola Montez), a fancy American pen, a suit from London, and “vented shoes of Egyptian leather,” while Momo (Claude Mansard) insists his supposedly silk scarf is actually made of metal and Japanese. Fido refuses to believe it’s either one, and when Momo swears, “If I’m lying, may my mother drop dead this instant,” Truffaut cuts to an oval-shaped silent-film insert of a lady keeling over, kicking up her heels as she hits the floor.

In fact, there are a couple of other ladies who die in this movie, both lovers of the title hero (Charles Aznavour), and it isn’t at all funny when they do. But part of Truffaut’s methodology throughout is to keep pulling the rug out from other our feet. Gangsters are usually figures of menace, but these two are like the kids proudly showing off their toys to one another in the first scene of Zero de conduite, while Fido plays the somewhat patronizing but ultimately skeptical grownup. And Truffaut validates his skepticism with a breezy cutaway.

***

Scene

2003 / Goodbye, Dragon Inn – The shot of the empty auditorium near the end.

Taiwan. Director: Ming-liang Tsai. Original title: Bu san.

Why it’s Key: A minimalist master shows what can be done with an empty movie-theater auditorium.

One singular aspect of Ming-liang Tsai’s masterpiece is how well it plays. I’ve seen it twice with a packed film-festival audience, and both times, during a shot of an empty cinema auditorium, where nothing happens for over two minutes, you could hear a pin drop. Tsai makes it a climactic epic moment.

Indeed, for all its minimalism, Goodbye, Dragon Inn fulfills many agendas. It’s a failed heterosexual love story, a gay cruising saga, a Taiwanese Last Picture Show, a creepy ghost story, a melancholy tone poem, and a wry comedy. A cavernous Taipei movie palace on its last legs is showing King Hu’s 1966 hit Dragon Inn to a tiny audience — including a couple of the film’s stars, who linger like ghosts after everyone else has left — while a rainstorm rages outside. As the martial-arts classic unfolds on the screen, we follow various elliptical intrigues in the theater, such as the limping cashier pining after the projectionist, whom she never sees. Tsai has a flair for imparting a commanding presence to seemingly empty pockets of space and time.

With the cashier, we peer at the end title on the screen. Then, in a shot lasting well over five minutes, the camera faces the empty auditorium as the lights flicker on and she enters with a broom on the right –recording her slow passage up one aisle, across the middle row, and down the other aisle until she exits on the left. Then we linger for two minutes more, communing with silence and eternity.

***

Scene

1955 / Track of the Cat – Robert Mitchum burning a page from a book of poetry containing the poem “When I have fears that I will cease to be” in order to stay alive.

U.S. Director: William A. Wellman. Cast: Robert Mitchum.

Why It’s Key: John Wayne’s only art movie as a producer suddenly turns literary.

John Wayne produced this strange art film as a favor to William A. Wellman, who’d recently directed him in the highly successful The High and the Mighty. What Wayne actually thought of this curiosity — adapted by ace screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides from an allegorical novel by Walter Van Tilburg Clark — is apparently unrecorded. Sometimes it suggests an American version of Carl Dreyer’s Ordet in its portrait of a dysfunctional, mainly male rural family in the middle of nowhere.

The action mainly unfolds in a house where family members quarrel and bicker, but we periodically cut away to a nearby snow-covered mountain where first Arthur (William Hopper), then his brother Curt (Robert Mitchum), hunt for a black panther that we hear but never see. The film’s in Cinemascope and color, but virtually all of it’s designed in black and white, apart from Curt’s red and black coat. Then, after Arthur is killed by the panther, and Curt finds his body, he switches his own coat with Arthur’s black and white one before sending Arthur’s body back home on his horse. He holes up in a cave when a storm starts up, and reaching into Arthur’s coat pocket, finds a volume of John Keats’ poetry. Still later, while trying to keep from freezing to death outside, he feeds a fire with the Keats poem that begins, “When I have fears that I will cease to be…” Addressing his dead brother, he says, “The only time any good came from your moanin’, Boy.”