From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 496). — J.R.

Petite Marchande d’Allumettes, La

(The Little Match Girl)

France, 1928

Directors: Jean Renoir, Jean Tedesco

Cert-U. dist–Contemporary. p–Jean Renoir, Jean Tedesco . asst. d–

Claude H eymann. Simone Hamiguet. Sc–Jean Renoir. Based on the

storv bv Hans Christian Andersen. ph–Jean Bachelet. a.d—Eric Aës.

m -excerpts from works by –Schubert, Strauss, Wagner, Mendelssohn.

m. d–Manuel Rosenthal, Michael Grant. Lp—Catherine Hessling (Karen,

the Little Match Girl), Jean Storm (Young Man/Soldier), Manuel Raby

[Rabinovitch] (Policeman/Death), Amy Wells (Dancing Doll). 1,030 ft.

29 mins. (16mm; also available in 35 mm.). English titles.

Karen leaves her humble-cottage to sell match boxes under a heavy

Snowfall. She gazes wistfully at a handsome young man emerging

from a restaurant, then looks through a frosted pane at the people

eating inside until boys throw snowballs at her. As she gathers up her

spilled boxes a policeman arrives, and together hey look at a display

of dolls and other toys in a shop window. After lighting matches in

an effort to warm herself, she falls asleep and dreams that she enters

the toy shop — having become the same size as the dolls –- and sets

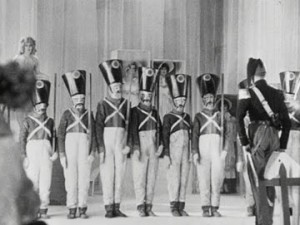

them all in motion. The young man glimpsed on the street appears

as Captain of the toy soldiers and declares his devotion to her,

magically conjuring up a tableful of food; but before she can eat, a

jack–in-the-box identifying himself as Death — another incarnation

of the policeman takes her carving knife and orders the soldiers

and other toys to stop. She and the Captain ride off into the clouds

with Death in pursuit; the men cross sabres, the Captain is slain,

and Death carries Karen’s prone body to a rocky hill and lays her

beneath a cross, which sprouts into a rose tree. Petals falling on her

face merge into snowflakes as the dream fades; passers-by stand

over Karen’s dead body, surrounded by burnt matchsticks in the

snow.

Asked by Rivette and Truffaut in a 1954 interview whether the

trucages in La Petite Marchande d’Allumettes represented his only

“complete experience” in that realm, Renoir replied: “No; I began

making films out of love for trucages. I had no intention of writing,

being an author, inventing stories — my ambition was to make

trucages, and I haven’t done badly since then”. The point is a crucial

one. If this lovely studio-cultured blossom seems at first glance an

exception in Renoir’s career — shot and processed in its entirety in

the attic of the Théâtre Vieux Colombier, in a project so artisanal

and home-made that Renoir and his partner Jean Tedesco supplied

their own electricity, painted the sets, and (with some outside

assistance) built their own lighting system to accommodate their

innovative use of panchromatic stock for interiors — it is a deceptive

first glance. Even as indefatigable a defender of Realism as André

Bazin tries to sneak this film in the back door by defending it as

“the incursion of Renoir’s realism into the themes and techniques

of the avant-garde”, and he is at least halfway right. From the evident

artifice of the toy train chugging through Karen’s impoverished

neighbourhood to the ‘life-like’ sizes and gestures of the toys in her

dream, The Little Match Girl serves as testimony to the unreality of

‘reality’ and the solidity of dreams. Forty-one years later, Renoir

expresses the same notion in the first episode in his Petite Théâtre,

explicitly harking back to his love of Andersen and evoking the

earlier film while inverting some of its details (such as emphasizing

the restaurant diners’ view of the beggar instead of the other way

round, and reducing the dream itself to a single image) to arrive at a

comparable conclusion. Even before she enters the momentary

solace of sleep, Karen is herself a figure of pure fantasy in the

measured doll-like comportment of Catherine Hessling. And much as

her match flames briefly illuminate visions in her mind’s eye (an

enormous sunflower, a Léger-like Christmas tree), thereby equating

life itself with the capacity to dream, the fancy table of food she is

unable to enjoy in the dream expresses her actual hunger more

concretely than her glimpse of guests in the restaurant. Renoir has

noted that neither the music accompanying the film nor the titles

belong to his and Tedesco’s conception (a different score was

originally prepared for a small ‘live’ orchestra, and no titles at all

were intended), and the faded textures of the print under review

suggest a further loss, but far from an essential one: the beauty and

splendor of Renoir and Tedesco’s attic of wonders still shine

implacably through the ravages of nearly half a century.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM