This appeared in the April 4, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Citizen Ruth

Rating * (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Alexander Payne

With Laura Dern, Swoosie Kurtz, Kurtwood Smith, Mary Kay Place, Kelly Preston, M.C. Gainey, Burt Reynolds, and Tippi Hedren.

Inventing the Abbotts

Rating *** (A must see)

Directed by Pat O’Connor

Written by Ken Hixon

With Joaquin Phoenix, Billy Crudup, Will Patton, Kathy Baker, Jennifer Connelly, Liv Tyler, Joanna Going, Barbara Williams, and Michael Sutton.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

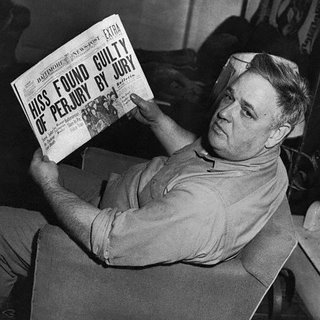

The best insight into 20th-century repression I’ve encountered recently is contained in Sidney Blumenthal’s piece about Whittaker Chambers in the March 17 issue of the New Yorker. Chambers “lived in a time when it was easier to confess to being a [communist] spy than to confess to being a homosexual,” Blumenthal notes. He also remarks that Chambers’s behavior as a spy — “furtive exchanges, secret signals, false identities” — resembled his behavior as a homosexual, and that he “and a pantheon of anti-Communists for whom conservatism was the ultimate closet — J. Edgar Hoover, Roy Cohn, and Francis Cardinal Spellman — advanced a politics based on the themes of betrayal and exposure, ‘filth’ (as Hoover called it) and purity.” In other words, if communist ideals rested on a love for one’s fellow man (as 50s macho-centric jargon had it), then literally loving one’s fellow man must have produced all sorts of psychosexual confusion.

This perception clarifies some of the sexual panic that ran concurrently with the cold war demonology of communism in mid-century American culture. And if one wonders what kind of repression and panic inform end-of-the-century American culture, it seems that shame and fear regarding class have replaced earlier feelings about the dangers of sex. Like sexual panic in the 50s, twisted manifestations of class fears are everywhere, though it’s not a subject often discussed in polite company. One hears plenty about crime, disease, racism, drug use, and homelessness as general conditions affecting the poor but much less about not having money as a social condition in itself — a condition that’s perceived as a disgrace, and one amplified rather than clarified, much less alleviated, by recent legislation. If the worst social legacy of 50s homophobia was homosexual self-hatred — a legacy writ large in the discourse of Chambers, Hoover, and company — the worst social legacy of economic callousness today may be the self-hatred of the poor and the politically powerless.

Contemporary pop culture reveals symptoms of this shame and panic everywhere: what else were the most recent Oscar awards about? [2009 note: The most prominent winners were The English Patient, Shine, Fargo, and Jerry Macguire.] , I’m thinking not only of the impulse to reward movies that spoke up for social rejects, thereby deflecting attention from the Academy’s own rejections — a brand of Oscarthink that in 1955 deemed Marty the best picture of the year — but also of the apparent conclusion that “independent” movies consistently outshone studio product. Yet if Disney is distributing The English Patient and Sling Blade, and studio-controlled rather than independent theaters are showing all the best-picture nominees, calling these multimillion-dollar productions independent is merely an attempt to rationalize a process of upper-class decision making into something resembling a populist triumph.

To be fair, neither the “independent” Disney-distributed Citizen Ruth, which I loathe, nor the Twentieth Century-Fox release Inventing the Abbotts, which I like, could ever hope to be nominated for Oscars. But both are fundamentally about class panic, even though Citizen Ruth never owns up to it and Inventing the Abbotts can safely broach the matter only because the film is set in the late 50s and early 60s. In other respects these pictures are drastically different, the first an irreverent satire about pro- and antiabortion activists converging on a hapless, homeless doper who’s pregnant for the fifth time, and the second a coming-of-age story about a couple of working-class brothers and three upper-class sisters in a small town in Illinois.

Some critics have praised writer-director Alexander Payne’s Citizen Ruth because it refuses to judge the title heroine (Laura Dern) the way that the jeering stereotypical right-to-lifers and pro-choice pundits competing to appropriate her do. But there’s no possibility of judging her because Payne has such a reduced notion of her character, a notion Dern fully adopts, that it makes any judgment superfluous. Like Alex in A Clockwork Orange, Ruth is a prole and a primitive motivated only by instant gratification — in her case, paint or glue fumes, booze, TV, Walkman tapes, and money — and apart from a few infantile crying jags, angry rejoinders, and idiotic mimicry of whomever she’s with, that’s about the extent of her personality. We aren’t expected to be curious at the beginning about where she comes from or at the end about where she’s going. At best, her rejection of both sides of the abortion debate and escape with a bagful of loot — armed with a gun she’s somehow acquired through an editing error — are meant as a triumphant corrective to the cant and hypocrisy of people who presume to try to change the world. In other words, Payne is just as guilty of using her as a figurehead for his ideas — most of them about the stupidity and futility of politics — as are the targets of his satirical abuse. Her running off makes for a nice closing image, but everything leading up to it is a fusillade of cheap shots.

After playing the pop standard “All the Way” over the credits, Payne cuts to Ruth humping another lowlife on a bare mattress in a hyperbolically grubby flat. As soon as they’re done, her designated fellow creep ejects her into the hallway — along with her portable TV, which he smashes when she insists on taking it with her. After descending a dingy fire escape and crossing a trashy vacant lot, she shatters the windows of his beat-up car with a rusty pipe before walking to her brother’s house in a slightly less ratty neighborhood. Her brother — who’s raising two of her four kids (the other two were put up for adoption) — refuses to take her in or let her stay in his garage, and when he reluctantly hands her $15, she immediately spends it on a can of spray paint, which leads to her 16th arrest for paint inhalation that year.

The film’s overuse of setting to define class is intimately related to its reduced definition of character, and apart from Ruth’s incarceration, the same stylistic reliance on stereotypes applies throughout. When Ruth discovers she’s pregnant again, she gets charged with a felony for endangering the fetus through her drug abuse but is offered a reduced sentence if she’ll agree to have an abortion. Imprisoned for the time being, she shares a cell with some pro-lifers, and a pro-life couple (Kurtwood Smith and Mary Kay Place) eventually puts up her bail and takes her home in the hope of convincing her to have her child. At this point the film reverts to its preferred mode, satire as class denigration — specifically, ridiculing the couple’s tacky Christian home, whose petit bourgeois furnishings and house rules (“We don’t really sit in those chairs“) are indexes of the couple’s fraudulence.

The film’s amused contempt for Ruth’s white-trash surroundings, passed off as some sort of realism, is superseded by mockery (pitched as satire) of the couple’s blue-collar home and all that goes with it — including their charitable and compassionate impulses. Repeatedly the film associates grotesque class trappings with political convictions of every stripe. This is where Citizen Ruth decisively parts company with a humanistic comedy of class difference like Boudu Saved From Drowning; even Sullivan’s Travels, which mocks a millionaire’s political idealism, shows respect for poor and rich alike. But as this film moves up the economic ladder — first to the home of a middle-class lesbian pro-choice couple (Swoosie Kurtz and Kelly Preston) plastered with leftist and vegetarian slogans and filled with dresses from Guatemala, then to the hotel room (and boy masseur) of a wealthy pro-life minister (Burt Reynolds) and the helicopter of a wealthy pro-choice celebrity (Tippi Hedren) — its derision never varies. Less ridiculed is a Vietnam-vet biker with an artificial leg (M.C. Gainey) who improbably works security for the pro-choice contingent and, even more improbably, coughs up $15,000 he’s stashed away from an “Agent Orange settlement” to match the pro-lifers’ proffered bribe to the heroine.

But to say that Payne heaps scorn on rich and poor alike (while betraying an interesting faith in our government’s commitment to injured veterans) overlooks the fact of his contempt for political passion of any kind. In a way this movie duplicates the 1955 anticommunist tract Trial, a Hollywood picture in which a Mexican youth on trial for murder becomes the unwitting tool of scheming commies. But in Citizen Ruth the very idea of political activism supplants the notion of a red menace. It’s a very fashionable form of defeatism — the ultimate political closet for those afflicted with class fears, much as political conservatism was for gay men of the 50s. And the “daring” conviction that slackers like Ruth are better off without our help and even our interest is not inconsistent with the recent policies of either Newt Gingrich or Bill Clinton. (Ironically, an old-fashioned Hollywood film like That Old Feeling, also opening this week, is far more challenging to status quo attitudes.) Within such a climate, disgust for human possibility marketed as hip irreverence can be counted on like money in the bank — unless the class panic that’s brought it into being becomes too apparent, as it is here, and leaves an acrid aftertaste.

Class panic may be at the root of what happens in Inventing the Abbotts, but in this case the story and characters are far from simple, and they grow in density over the course of the deceptive plot. The film’s major strength is its carefully structured, finely tuned script by Ken Hixon, adapted from a short story by Sue Miller. It chronicles the lives and interactions of two working-class brothers, Doug and Jacey Holt (Joaquin Phoenix and Billy Crudup), between 1957 and 1960 — their last years in high school and first years in college — with the three daughters of a wealthy family in the same Illinois town, the Abbotts. Class differences and the panic arising from those differences, on both sides of the tracks, are the central subjects.

Though it’s the brothers’ panic that the film emphasizes — which is why it’s called Inventing the Abbotts and not Inventing the Holts — the myths and taboos separating the families are fully experienced on both sides, and it takes the entire length of the film for them all to be aired. Fairly early on we’re told that Doug and Jacey’s father died years ago in a freak accident deriving from a bet with Lloyd Abbott (Will Patton); that Lloyd’s wealth comes in part from their father’s patent, which Lloyd purchased shortly after the accident from the boys’ mother (Kathy Baker); and that Lloyd may have been sexually involved with their mother. But by the time the film is over, our understanding of all these matters is altered.

Doug, the younger brother and narrator (recounting the story from the vantage point of someone much older), is shy and awkward with women, while Jacey is a ladies’ man. (Paradoxically, as we eventually discover, the sexual behavior of both brothers comes largely from their sense of class.) Jacey at 17 gets involved first with Eleanor (Jennifer Connelly), the youngest and most rebellious of the Abbott girls, while Doug at 15 forms an uneasy friendship with the similarly awkward Pamela (Liv Tyler), the middle daughter, who’s the same age he is.

Apart from the script, it’s the actors who make this a film worth seeing; all of them look and sometimes even act like real people rather than types or icons, and behind their interactions can be felt the depths of lived experience (Phoenix, Tyler, and Baker are especially fine). Though Pat O’Connor’s direction was certainly instrumental to these performances, he falters at times in conjuring up the place and period. Set in Illinois and Pennsylvania, the film was shot in California, and despite a lot of apparent effort to get the details right, the world and era established by this film rarely seem to extend very far beyond the borders of individual shots and locations. It’s possible that O’Connor’s remoteness from the characters’ backgrounds — he’s Irish — is partially responsible. But the Scottish writer-director Bill Forsyth fully overcame a similar problem in Housekeeping, which was also set in small-town America during the 50s, so I suspect other factors are involved as well.

Because the story is mainly concerned with the characters’ psychological development, this limitation isn’t crippling: the authenticity of their feelings counts for more. Ultimately this film evokes another re-creation of the 50s — Peter Bogdanovich’s 1971 The Last Picture Show — more than any movie made during the 50s, a fact no doubt appropriate to a work concerned more with understanding than with evocation. More pertinent, because it shows how class panic not only affects behavior but forges identities and destinies, Inventing the Abbotts has more to say about our culture today than most movies set in the present, Citizen Ruth included.