This was originally published in Cineaste in June 2003. To see a beautiful new restoration of Paradjanov’s long-unseen and very beautiful Kiev Frescoes, go here: https://kinonow.com/kyiv-frescoes/ —J.R.

It’s astonishing how little we still know about Soviet cinema in general and Sergei Paradjanov (1924-1990) in particular, and it’s possible that Soviet history has something to do with this —- a desire not to remember pointing to an even more basic desire not to know. Considering what a teller of tall tales Paradjanov was himself, it seems inevitable that he would only add to the confusion while he was alive rather than clear up most of the muddle. Writing about three Paradjanov features that were showing in Chicago 13 years ago, I noted that his name couldn’t be found in Ephraim Katz’s Film Encyclopedia or in the indexes of books by Pauline Kael, Stanley Kauffmann, or John Simon (among many others), and lamented that as far as I knew, no one anywhere had yet written a book or monograph about him. [2022: This is no longer the case.See, in particular, https://www.amazon.com/Cinema-Sergei-Parajanov-Wisconsin-Studies/dp/0299296547/ ] I was writing only a month after he visited the west for the first time —- attending the Rotterdam Film Festival, where I was fortunate enough to be present —- and this was only four years after he resumed work as a filmmaker following something like 16 years of enforced silence, either as a prisoner or as a director whose proposed projects since Sayat Nova in 1969 had all been rejected.

What were his crimes? In the Stalinist period, Paradjanov was reportedly detained in a “re-education” labor camp for homosexuality. In the mid-60s, shortly before Khrushchev was deposed, he was attacked in the press for being a formalist; after he signed letters in support of Ukrainian dissidents, he was called a “Ukrainian nationalist”; he was never allowed to finish his 1965 Kiev Frescoes due to “bourgeois subjectivism and mysticism” and “ideological deviation”; after many battles over his Armenian masterpiece Sayat-Nova, the film was re-edited into a version 20 minutes shorter by director Sergei Yutkevich. After his next dozen or two dozen film projects were rejected (accounts differ), he was arrested in late 1973 for charges that ranged from dealing in foreign currency, speculating on artworks, and stealing icons to spreading venereal diseases, inciting suicide, and homosexuality, and sentenced to five years of hard labor —- a term eventually reduced to four years after a petition of protest was circulated internationally. According to one account, he admitted to being bisexual at his trial, but it seems that most or all of the charges were specious and that his “real” crimes were being an eccentric and a “troublemaker”. (Yuri Ilyenko — cinematographer on Paradjanov’s masterpiece Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, who attended the trial —- once told me that a man he was accused of raping was built like a football player; considering that Paradjanov himself was roughly the height of Mr. Natural, the charge was visibly ridiculous.)

Four years later, he was arrested a third time for attempting to bribe an official, then cleared of charges after about half a year in prison. The first feature he was able to make after Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) and Sayat-Nova (1969) was The Legend of Suram Fortress (1984), followed by the much slighter Ashik Kerib (1988) two years before his death from cancer.

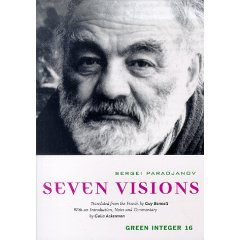

Today, there are many books about him, including at least a couple in French, one of which was translated into English a few years back —- a lovely small volume called Seven Visions (Green Integer, 1998) in which Paradjanov collected a few of his film scenarios, only four of which ever got realized in any form. Kiev Frescos and Sayat-Nova both got recut, though luckily Paradjanov’s original version of the latter film survived (luckier still, this is the version now available on DVD), and he only lived long enough to film a fragment of The Confession (for me, the greatest of his works after Sayat-Nova, for all its brevity, as well as the most visionary — though unluckily, it isn’t available on DVD, and neither is Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, the second best feature of his that I’ve seen); Swan Lake, the Zone was realized by a friend, the aforementioned Yuri Ilyenko, who was able to screen it for Paradjanov prior to his death. (Ilyenko told me he was delighted by a detail that was inserted in the film partially for his own benefit —- a photograph of him from a film magazine that identified him as a “maestro”.)

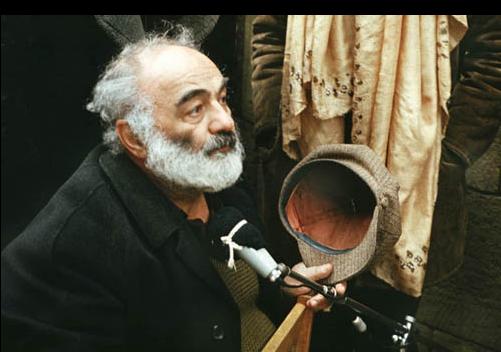

Born Sarkis Paradjanian to an Armenian family in Tblissi, the capital of Georgia, Paradjanov (as he was known once his name became Russified) grew up in an ethnic and religious melting pot; for centuries, Galia Ackerman writes in the Introduction to Seven Visions (the source of most of the above information), “each child spoke three languages: Georgian, Armenian, and Azeri, no two of which belong to the same linguistic family.” This background is perhaps where some of his troubles with Soviet authorities began, once he became known as a folklorist committed to the cultures of the Ukraine (Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors), Armenia (Sayat-Nova), and Georgia (many shorts, and eventually The Legend of Suram Fortress). Admittedly, he was also interested in adapting fairy tales by the Danish Hans Christian Andersen and the Russian Mikhael Lermontov (Ashik Kerab), and he certainly didn’t consider himself an opponent of the Russian state: at his Rotterdam press conference, where he came across as an ebullient and earthy, roly-poly Mr. Natural in body language as well as size — typically responding to each question with a manic and charismatic 45-minute performance that had only a glancing relation to the query posed —- he even criticized his Russian friend Andrei Tarkovsky for defecting, arguing that he could have made both of his final features in Russia. (Significantly, his favorite filmmaker seemed to be Pier Paolo Pasolini; practically everyone else he mentioned —- including Eisenstein and Buñuel as well as Tarkovsky —- was criticized for being too middle-class.)

***

Not having seen any of Paradjanov’s early features, apart from a few excerpts in various documentaries, I find it impossible to weigh his last three features against everything else preceding them —- except to note that there appears to be a critical consensus that Sayat-Nova is his greatest film. (It is also the last feature on which he would take a script credit.) It was shot almost exclusively in frontal, hieratically composed tableaux that assume the shallow space of early cinema. While all these tableaux appear to have a literal or allegorical relationship to the life and work of Aruthin Sayadin, popularly known as Sayat Nova (the “King of Song”), and are arranged chronologically, the film veers closer to nonnarrative than it does to the continuity and development of a conventional biopic. Indeed, it seems curious that this film should be better known than Shadows, Suram Fortress, or Ashik Kerab, for it is a good deal more difficult and formally radical than all three. One useful route into the film is Paradjanov’s own identification with the legendary poet. The opening quotation from Sayadin can even be read as the director’s disclaimer: “My water is of a very special kind, / Not everyone can drink it. / My writing is of a very special kind, / Not everyone can read it. / My foundation’s made not of sand, / But of solid granite.” It’s worth noting that, like Paradjanov, Sayadin was born in Tbilisi to very poor Armenian parents, wrote and sang in different languages, and was banned from practicing his art in Georgia near the end of his life.

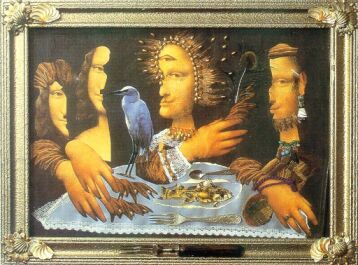

In other respects, we don’t have to decode the images in any systematic way in order to experience their haunting power. The opening shots show three pomegranates oozing red juice on a white tablecloth, a bloodstained dagger, bare feet crushing grapes, a fish (which promptly becomes three fishes) flopping between two pieces of driftwood, and water falling on books. (One sequence shortly afterward shows him surrounded by a sea of open books on the roof of an ancient building, their pages riffled by the wind as he looks at pictures in one of them.)

Some critics have related the pomegranates and the dagger to the Turkish massacres of Armenians, but another clue is offered by a quatrain of Sayadin’s poetry in this section, which the images can be said to gather around:

While the child is growing,

The soul ripens, like fruit,

Through three elements;

Love of books,

Love of God,

Love of songs.

As the film and the poet’s life progress, many of the images become a good deal more complex. In one shot inside a spare white interior, a female figure dressed in red performs an elaborate pantomime with a transparent red cloth over the dummy of an outstretched body; behind her, an empty ornate picture frame suspended from the ceiling swings back and forth; behind that is a rotating statue of a cherub, and behind that, a motionless and indistinct red painting or fabric. Yet even compositions as intricate as this one register as primitive and childlike—-images that giggle with delight rather than brood or ponder (as images in films by Tarkovsky and Sokurov more commonly do), often provoking us to do the same.

Much of this conscious naïvité spills over into The Legend of Suram Fortress, albeit in a very different context. After films set in the 19th and 18th centuries (i.e., Shadows and Sayat-Nova), this one goes all the way back to the Middle Ages, and medieval art, theater and literature form much of the basis of the style here. Though the frontal shooting style of Sayat-Nova is partially echoed, a deeper use of space and a much more expansive use of landscape make the visual style closer to tapestries than to icons. And continuity cutting, which is still used in certain portions of Sayat-Nova, is eliminated entirely here until the climactic sequence, making each shot an autonomous event.

Paradjanov claimed that all the props and costumes used in Suram Fortress came from his own house, where he stockpiled such items for years —- a reflection of his low-budget method of shooting that helps to explain how he can make his retellings of impersonal myths so personal, and occasionally calling to mind Joseph Cornell’s boxes. (Apparently because he was less fluent in Georgian than he was in Ukrainian, Armenian, and Russian, he used one of the lead actors here, Dodo Abashidze, as a codirector because he could communicate better with the other Georgian actors. I’ve been unable to determine whether David Abashidze, credited as Paradjanov’s assistant on Ashik Kerib, was a relative.) One of the major characters, Osman-Agha, whose recounted life forms a lengthy digression dropped into the middle of the plot, is a Georgian forced to renounce Christianity as a young man and become a Muslim, and in many respects the film’s plot as a whole deals with the encounter between east and West that makes the eventual construction of the fortress —- finally effected by a human sacrifice—possible.

Subtitled The Lovelorn Minstrel and dedicated to the memory of Tarkovsky (who had recently died), Ashik Kerib is the most minor of Paradjanov’s late features, though it obviously has much personal and autobiographical and personal significance. Loosely adapted from Lermontov’s tale about a Turkish minstrel and maiden, it has a style somewhat akin to the frontal tableaux vivants of Sayat-Nova with the addition of some camera movement, dialogue, and offscreen narration; the Azerbaijani dialogue and the Georgian narration tell the story proper, and the limitation of the visuals in this case —- though they are

Certainly richly colored, mysterious, and magical — is that they tend to be more illustrative than those in Paradjanov’s three preceding features.

The two DVDs of Paradjanov’s work released by Kino Video are both well worth having. It’s regrettable that Sayat-Nova (also known as The Color of Pomegranates), available on one, and both The Legend of Suram Fortress and Ashik Kerib, available on the other, are subtitled rather sparsely, but their sounds and images are beautifully preserved. Included with Sayat-Nova are two bonuses: Hagop Hovnatanian, a ten-minute film by Paradjanov dating from 1965 (around the same time he made Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors and Kiev Frescos), and Ron Holloway’s 57-minute Paradjanov: A Requiem (1964). The first of these has no subtitles at all, but is a wonderful distillation of Paradjanov’s special brand of poetry —- a crisp and playful montage of objects, portions of paintings, settings, little boys, and other familiar parts of his universe. Holloway’s documentary is basically a heap of interviews, home movie footage, stills, photographs, and clips, put together rather formlessly and not always well selected. (I especially regret the absence of any part of The Confession, and the inadequate representation of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.) But it’s still invaluable for its glimpses of Paradjanov’s earlier work of the 50s and 60s and its contributions to our still highly sketchy grasp of his life and career, and it will have to do until something more comprehensive comes along.