From Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 496). Blythe Danner was a classmate of mine at Bard College, where I had the privilege of seeing what a gifted actress she already was (I remember especially her performance of one of the lead roles in Jean Genet’s The Maids) and the pleasure of accompanying her once or twice on the piano when she performed as a jazz singer (in particular, on “‘Round Midnight”). — J.R.

Lovin’ Molly

U.SA., 1973Director: Sidney Lumet

Bastrop, Texas. The lives of three characters, narrated by each in

turn. 1925, Gid (Anthony Perkins): Gid and Johnny (Beau Bridges)

are friends whocompete for the favors of Molly (Blythe Danner),

who likes themboth. When Gidproposes to Molly, she replies

that she’d rather have sex with him for its own sake, not as part

of a marriage contract, and invites himto join her in a nude swim,

but he refuses. She goes to a dance with Eddie (Conrad Fowkes),

another local boy, and Johnny picks a fight with him. Gid sleeps

with her for the first time, and is shocked to discover she isn’t a

virgin. On a train to the Panhandle to sell his father’s cattle, Gid

attacks Johnny for sleeping with Molly and not proposing to her, but

then discovers that Eddie slept with her first. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 13, 1990). — J.R.

THE COOK, THE THIEF, HIS WIFE & HER LOVER

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Peter Greenaway

With Richard Bohringer, Michael Gambon, Helen Mirren, Alan Howard, and Tim Roth.

On the face of it, this movie seems to have a good many things going for it. Although he was born in 1942, Peter Greenaway is still probably the closest thing that the English art cinema currently has to an enfant terrible. A former painter and film editor who started making experimental films in the mid-60s, he achieved an international reputation with The Draughtsman’s Contract in 1982; he went on to become a star director and cult figure in Europe with several TV films and three more features that had considerable success in both England and France as well as on the international festival circuit — A Zed & Two Noughts (1986), The Belly of an Architect (1987), and Drowning by Numbers (1988) — although they have had only limited circulation in the U.S. A fair number of my film-buff friends swear by him, and he is commonly regarded as the most “advanced” art-house director currently working in England.

Greenaway’s latest feature makes sterling use of many of his longtime collaborators: Sacha Vierny, one of the best cinematographers alive (working here in ‘Scope), whose credits include Hiroshima, mon amour, Last Year at Marienbad, Muriel, Belle de jour, and Stavisky, as well as films by Raul Ruiz and Marguerite Duras; composer Michael Nyman, a sort of neoclassicist who has worked for everyone from the Royal Ballet to Steve Reich to Sting; and production designers Ben Van Os and Jan Roelfs, former interior designers who have worked in the Dutch film industry since 1983. Read more

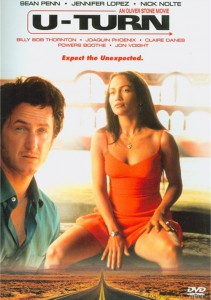

From the Chicago Reader (September 30, 1997). — J.R.

A fairly enjoyable piece of junk from Oliver Stone (1997) that occasionally recalls Dennis Hopper’s The Hot Spot — sleazy southwest burg seething with creeps, sexpots, and protracted grudge matches — and is limited only by its occasional pseudoexperimental tics (a carryover from Natural Born Killers) and by its determination to extend its hyperbolic noir plot beyond two hours. Sean Penn plays a con man whose car breaks down en route to Las Vegas, where he’s supposed to settle a debt; Billy Bob Thornton, as the ornery mechanic who extends his stay, is the first in a string of overblown caricatures that for better or worse define the movie — others are offered by Jennifer Lopez, Nick Nolte, Julie Hagerty, Powers Boothe, Joaquin Phoenix, Jon Voight, Claire Danes, Bo Hopkins, Laurie Metcalf, and Liv Tyler. The tricky and tricked-up script is by John Ridley. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Cinema Journal 26, No. 4, Summer 1987. — J.R.

Dialogue

Jonathan Rosenbaum Responds to Robin Bates’s “Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud’s Impact on Early Audiences” (which appeared in Cinema Journal, Winter 1987)

Having been invited to respond briefly to Robin Bates’s “Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud’s Impact on Early Audiences” in the Winter 1987 Cinema Journal, I should stress at the outset my sympathy with the main objectives of this essay, particularly as they are expressed in the closing paragraph. While my own recent Welles-related research has concentrated more on films and scripts that are not yet part of the public record,’ readers of my book Moving Places (Harper & Row, 1980) will know that I am also deeply concerned with the personal and historical dimensions of reception. Arguing that Citizen Kane in general and Rosebud in particular had “healing powers” in 1941 which are less available to us now, and that “audiences of the past … were no less sophisticated than audiences of today,” Robin Bates affords us a number of valuable historical insights, but his argument also raises certain methodological issues which I would like to explore. Although Bates has a commendable desire to open us up to the potential wisdom of the past (as exemplified by a retrospective statement about Rosebud from his father, Scott Bates, which opens his article), his means of fulfilling that desire depend on various forms of closure which I find problematical. Read more

From The Oxford-American, issue #42, Winter 2002. — J.R.

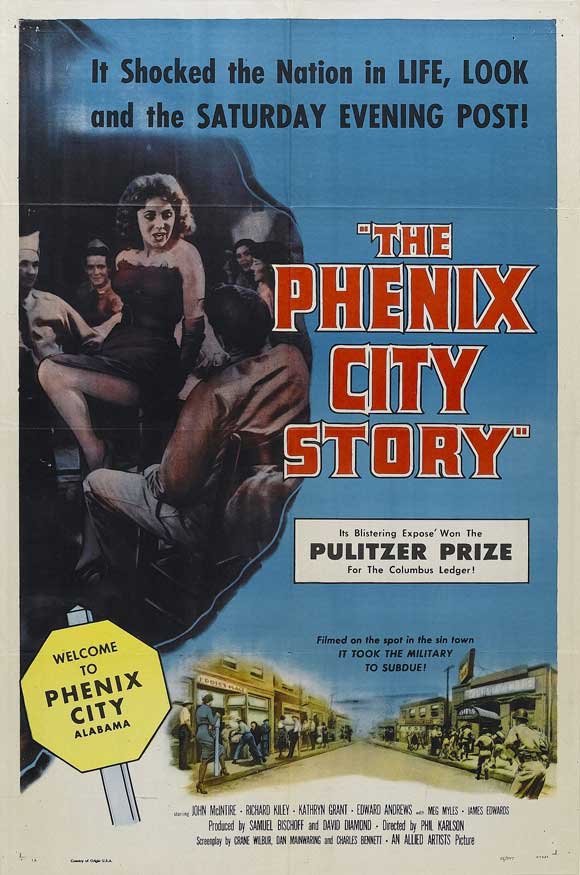

Karlson pushes and punches, but he’s good at it. He can dredge up emotion; he can make the battle of virtuous force against organized evil seem primordial. He has a tawdry streak (there’s an exploitation sequence with a nude prostitute being whipped), and he’s careless (a scene involving a jewelry salesman is a decrepit mess), but in the onrush of the story the viewer is overwhelmed….One would be tempted to echo Thelma Ritter in All About Eve –”Everything but the bloodhounds snappin’ at her rear end” — but some of the suffering has a basis in fact.

— Pauline Kael on Walking Tall (1974)

1. What Qualifies as Real

As an Alabama expatriate who fled north the first chance I could get, I didn’t keep my southern accent for long; it fell away, in a matter of months, like dead skin. The fact was — and is — that Alabama accents sound stupid to Yankees; and since I was both a teenager and trying hard to become a Yankee, they eventually began to sound stupid to me. Especially during the Civil Rights Movement, already in full swing by then, having a southern accent, if you were white, made you sound like a racist to some people, regardless of what you said or did. Read more

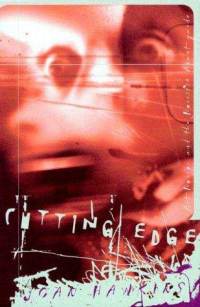

From Cinema Scope #19 (Summer 2004). This is obviously out of date in many respects, fourteen years later, but I repost it now a period piece. — J.R.

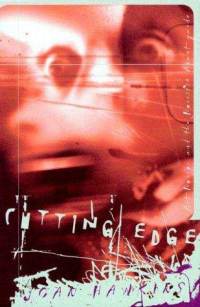

Joan Hawkins opens her book Cutting Edge: Art Horror and the Horrific Avant-garde (Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2000) with an interesting and useful observation:

“Open the pages of any horror fanzine —- Outré, Fangoria, Cinefantastique —- and you will find listings for mail-order video companies that cater to aficionados of what Jeffrey Sconce has called `para-cinema’ and trash aesthetics. Not only do these mail-order companies represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the video market, but their catalogs challenge many of our continuing assumptions about the binary opposition of prestige cinema (European art and avant-garde/experimental films) and popular culture. Certainly, they highlight an aspect of art cinema generally overlooked or repressed in cultural analysis: namely, the degree to which high culture trades on the same images, tropes, and themes that characterize low culture.”

As a direct illustration of Hawkins’ point, check out the web site www.xploitedcinema.com, a U.S. importer of overseas DVDs that also sells some domestic items and caters mainly to trash aesthetics, but among whose 86 pages of sex, horror, action, and gore items I also recently found an Italian two-disc set of my favorite Bernardo Bertolucci film, Prima della Rivoluzione/Before the Revolution (his second feature, 1964 — subtitled in English, along with all the extras), not to mention English-friendly Spanish and/or Mexican editions of my two favorite Alex Cox films (the 1987 Walker and the 1994 Highway Patrolman), a Spanish edition of Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight, a Korean edition of Sam Peckinpah’s scandalously underrated Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), and Italian editions of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1993). — J.R.

There’s a world of difference between the natural, “found” surrealism of Louis Feuillade’s lighthearted French serial (1914) and the darker, studied surrealism and campy piety of this 1964 remake by Georges Franju. Yet in Franju’s hands the material has its own magic (and deadpan humor), which makes this one of the better features of his middle period. Judex (Channing Pollack) is a cloaked hero who abducts a villainous banker to prevent the evil Diana (Francine Bergé in black tights) from stealing a fortune from the banker’s virtuous daughter. Some of what Franju finds here is worthy of Cocteau, and as he discovered when he attempted another pastiche of Feuillade’s work in color, black and white is essential to the poetic ambience. With Jacques Jouanneau and Sylva Koscina. In French with subtitles. 104 min.

Read more

Read more

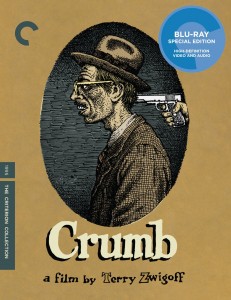

Written in 2010 for Criterion’s DVD and Blu-Ray. This is the second of my essays about Terry Zwigoff’s documentary; for the first one, written 15 years earlier, go here. — J.R.

Now that Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb is about fifteen years old, it seems pretty safe to say that it has evolved from being a potential classic to actually becoming one. But what kind? A documentary portrait of a comic-book artist, musician, and nerdy outsider? A personal film essay? A cultural study? An account of family dysfunction and sexual obsession? Or maybe just a meditation on what it means to be an American male artist — specifically, one so traumatized by his adolescence that he has never found a way of fully growing past it.

In fact, Crumb is all these things, with a generous amount of thoughtful art criticism thrown in as well. An old friend of Robert Crumb’s, Terry Zwigoff shot the movie over six years and edited it over three, and the multifaceted density and sometimes disturbing nature of what he has to show and say over two hours seems partly a function of the amount of time he had to mull it over. It’s worth adding that he was in therapy for part of that time, which surely had an impact on the film’s searching thoughtfulness and on Zwigoff’s own investment in the material. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 503). — J.R.

Farewell, My Lovely

U.S.A., 1975

Director: Dick Richards

Employing the same production team (Elliott Kastner and Jerry Bick) as The Long Goodbye and the same director of photography (John A. Alonzo) as Chinatown, Farewell, My Lovely resumes the Los Angeles private-eye cycle with a clear grasp of its immediate as well as its more distant precursors. Less individual than either Altman at his most eclectic or Polanski at even his least personal, Dick Richards nevertheless seems to have an almost equally distinct idea about what to do with his material — in this case, to honor it as closely as possible in its own generic terms and not aspire to bring to it any contemporary perspective more distancing than a warm and somewhat glazed-over nostalgia. Some of the consequences — like the wonderfully evocative pastel-like impressions of L.A. at night and a torchy orchestral theme by David Shire behind the opening credits, or the deliberate use of Forties film noir devices (first person voice-over narration, flashbacks framed by blurs, dime-store expressionism to render Marlowe’s loss of consciousness — recalling Dmytryk’s treatment of the same scene thirty years ago) — are immediately apparent. In other cases, including a self- conscious series of period references (DiMaggio’s batting record, Hitler’s invasion of Russia) and recreations (the lovingly detailed and mythically idealized sets), the results are less obvious: a sentimental softening of the Marlowe character throughout is so well integrated with the crisper aspects of his fancy rhetoric that Richards and scriptwriter David Zelag Goodman almost manage to transform the detective into a Sixties liberal who plays catch Fifties-style with a grinning mulatto child without seriously jarring the reverential tone. Read more

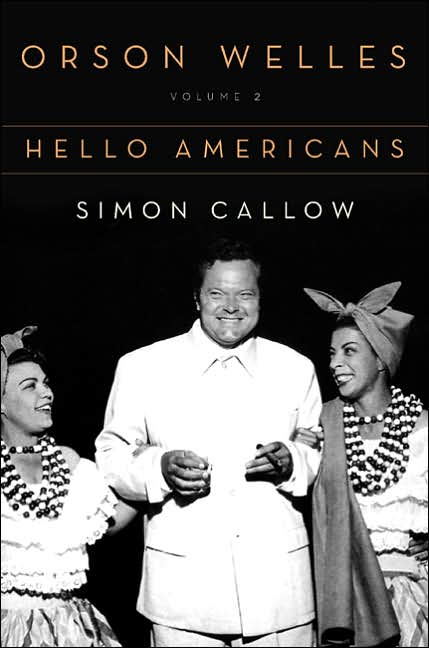

From Cineaste (Fall 2006). — J.R.

Orson Welles: Volume 2: Hello Americans

by Simon Callow. New York: Viking Adult, 2006. 528 pp., illus. Hardcover: $32.95.

“It seems to me there is a plain, if many-layered, truth to be told,” Simon Callow writes in his Preface to the second volume of his Welles biography — noting his impatience with academics whose sense of the truth is so far from plain that they can only countenance the term between quotation marks. It’s an understandable position for him to take, but he doesn’t always stick to it himself, and it’s hard to see how he could. In his second chapter, he asserts that, although no evidence supports Welles’s claim that Booth Tarkington had been his father’s best friend, it doesn’t matter at all “one way or the other; what is significant is that Welles believed it to be true, and wanted it to be true, and his conception of [Eugene Morgan in The Magnificent Ambersons] is certainly an idealized version of his father.” In other words, Callow is privileging one kind of truth over another — like all of us who write about Welles, including those pesky academics. Like it or not, it comes with the territory. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 14, 1997). — J.R.

Smilla’s Sense of Snow

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Bille August

Written by Ann Biderman

With Julia Ormond, Gabriel Byrne, Richard Harris, Robert Loggia, Vanessa Redgrave, Jim Broadbent, Peter Capaldi, Emma Croft, and Mario Adorf.

In a couple of memorably grouchy essays published in the mid-40s, critic Edmund Wilson expounded on his impatience with detective stories, confessing that “I finally got to feel that I had to unpack large crates by swallowing the excelsior in order to find at the bottom a few bent and rusty nails.” With a few honorable exceptions, such as Kiss Me Deadly and Cutter’s Way, conspiracy films have a similar drawback: the first half is more pleasurable than the second. I suspect the reason is that the thrill of sensing a vast, invisible network behind apparent chaos is more exciting and even satisfying than the prosaic explanation, which not only reduces possibilities and halts the imagination but, by creating closure, makes the whole experience seem rather disposable.

When conspiracy thrillers resemble detective thrillers — which is often — they have a built-in advantage, to my mind, because they typically approach the borders of fantasy or science fiction and play with the ambiguous line between the real and the fantastic. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 22, 1997). — J. R.

Despite its sentimental aspects, this youthful, semitragic tale of two Chinese mainlanders in Hong Kong — the wonderful Maggie Cheung (Actress, Irma Vep) and pop star Leon Lai — and their fluctuating relationship as friends and lovers is the most moving film I’ve seen yet about that city’s last years under colonial rule (though the film’s final sections are set mainly in New York, where both characters emigrate). I suspect many Chinese viewers feel the same, because the film cleaned up at this year’s Hong Kong Film Awards, sweeping no less than nine categories (including best director, film, screenplay, and actress). Set between 1986 and 1996, and visualized by director Peter Chan with a great deal of inventiveness and lyricism, this movie is full of heart and humor, capturing the times we’re living in as no Western film could. Watch for a charming cameo by Christopher Doyle, the premier cinematographer of the Hong Kong new wave, as an English teacher. Film scholar and former Chicagoan Patricia Erens, now based at Hong Kong University, will introduce the Friday screening. Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Friday, August 22, 6:00; Saturday, August 23, 8:00; Sunday, August 24, 4:00; and Tuesday, August 26, 7:30; 312-443-3737. Read more

This appeared in the April 4, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

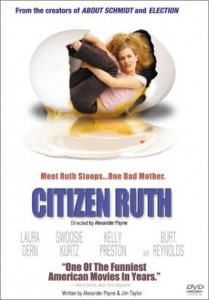

Citizen Ruth

Rating * (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Alexander Payne

With Laura Dern, Swoosie Kurtz, Kurtwood Smith, Mary Kay Place, Kelly Preston, M.C. Gainey, Burt Reynolds, and Tippi Hedren.

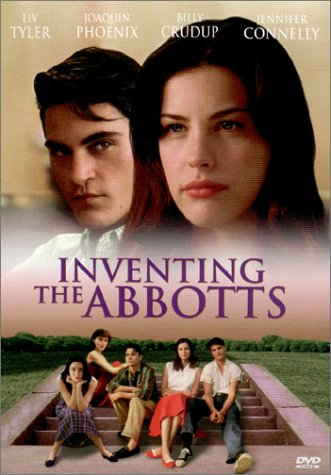

Inventing the Abbotts

Rating *** (A must see)

Directed by Pat O’Connor

Written by Ken Hixon

With Joaquin Phoenix, Billy Crudup, Will Patton, Kathy Baker, Jennifer Connelly, Liv Tyler, Joanna Going, Barbara Williams, and Michael Sutton.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

The best insight into 20th-century repression I’ve encountered recently is contained in Sidney Blumenthal’s piece about Whittaker Chambers in the March 17 issue of the New Yorker. Chambers “lived in a time when it was easier to confess to being a [communist] spy than to confess to being a homosexual,” Blumenthal notes. He also remarks that Chambers’s behavior as a spy — “furtive exchanges, secret signals, false identities” — resembled his behavior as a homosexual, and that he “and a pantheon of anti-Communists for whom conservatism was the ultimate closet — J. Edgar Hoover, Roy Cohn, and Francis Cardinal Spellman — advanced a politics based on the themes of betrayal and exposure, ‘filth’ (as Hoover called it) and purity. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 6, 1997). — J.R.

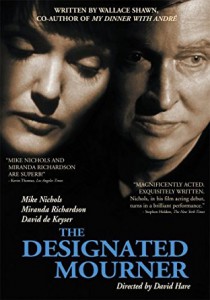

Another whimper from playwright Wallace Shawn about the fall of civilization — seen, as usual, more in terms of class than of intellect or aesthetics. References to such touchstones as John Donne and croquet contrive to suggest that maybe a little more than the takeover of the New Yorker by Tina Brown is at stake, but maybe not; the triumph of lowbrow vulgarity is perceived as the ultimate demise of mankind. Director David Hare films the play in its basic stage setting, three characters seated at a table, and trusts the pampered anguish of the material — the bemused and guilt-ridden but unquenchable sense of entitlement — to speak paradoxically for all of us. Mike Nichols, in his first screen performance, does a compelling job in the title role, his wide range of cartoon impersonations running the gamut from matinee-idol tics to scowls and nasal whines that evoke Shawn himself. Much flatter turns by Miranda Richardson and David de Keyser succeed only in flaunting the self-absorbed limitations of the play’s vision. If this is the way the world ends, I think I’d rather see it out with Schwarzenegger or Jim Carrey — anything but this dull pomposity. Read more

Written for the StudioCanal Blu-Ray of The Trial in the Spring of 2012. — J.R.

‘What made it possible for me to make the picture,’ Orson Welles told Peter Bogdanovich of his most troubling film, ‘is that I’ve had recurring nightmares of guilt all my life: I’m in prison and I don’t know why –- going to be tried and I don’t know why. It’s very personal for me. A very personal expression, and it’s not all true that I’m off in some foreign world that has no application to myself; it’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only one that’s really close to me. And just because it doesn’t speak in a Middle Western accent doesn’t mean a damn thing. It’s much closer to my own feelings about everything than any other picture I’ve ever made.’

To anchor these feelings in one part of Welles’ life, he was 15 when his alcoholic father died of heart and kidney failure, and Welles admitted to his friend and biographer Barbara Leaming that he always felt responsible for that death. He’d followed the advice of his surrogate parents, Roger and Hortense Hill, in refusing to see Richard Welles until he sobered up, and ‘that was the last I ever saw of him….I’ve Read more