From Cinema Journal 26, No. 4, Summer 1987. — J.R.

Dialogue

Jonathan Rosenbaum Responds to Robin Bates’s “Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud’s Impact on Early Audiences” (which appeared in Cinema Journal, Winter 1987)

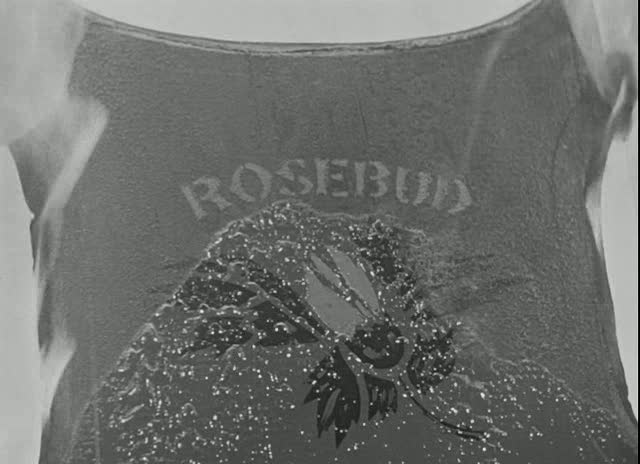

Having been invited to respond briefly to Robin Bates’s “Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud’s Impact on Early Audiences” in the Winter 1987 Cinema Journal, I should stress at the outset my sympathy with the main objectives of this essay, particularly as they are expressed in the closing paragraph. While my own recent Welles-related research has concentrated more on films and scripts that are not yet part of the public record,’ readers of my book Moving Places (Harper & Row, 1980) will know that I am also deeply concerned with the personal and historical dimensions of reception. Arguing that Citizen Kane in general and Rosebud in particular had “healing powers” in 1941 which are less available to us now, and that “audiences of the past … were no less sophisticated than audiences of today,” Robin Bates affords us a number of valuable historical insights, but his argument also raises certain methodological issues which I would like to explore. Although Bates has a commendable desire to open us up to the potential wisdom of the past (as exemplified by a retrospective statement about Rosebud from his father, Scott Bates, which opens his article), his means of fulfilling that desire depend on various forms of closure which I find problematical.

In the process of trying to bring academic legitimacy to a subjective poetic insight (the statement of Scott Bates), Robin Bates shows a great deal of attentiveness and ingenuity regarding certain matters while completely sidestepping certain others. Among the more glaring omissions are (1) a persuasive methodology for determining audience responses in 1941 as well as the present, (2) an account of the popularizing of Citizen Kane into a “comfortable” classic which has taken place since its release, (3) a distinction between journalistic and academic modes of discourse, and (4) a consideration of the suitability of The Citizen Kane Book as a privileged scholarly resource. Insofar as Robin Bates is interested in making a tidy package out of his argument, these are all factors that he has good reason to avoid. Because I am less interested in tidy packages and more concerned with the degree to which the past, like the present, is so proficient in offering up whatever we wish to find there, I hope Mr. Bates will not object if I introduce these few shadows into his world of certainties.

(1) How much can we know about the responses of thousands of spectators to a film forty-odd years later, much less today? Here is where the discrepancies between Bates’s research methods become most unsettling. While he is willing to travel all the way to the Welles collection at Lilly Library in Indiana in order to document one of the alleged sources of Rosebud, he goes no further than The Citizen Kane Book and Focus on Citizen Kane to chart contemporary responses to the film, and cites only five reviews drawn from these sources to support his argument. But how reliable are contemporary reviews as an index of audience responses? And how representative can five reviews be of an assumed critical consensus? The same problems apply to Bates’s citations of more recent, academic responses to Kane. By limiting his already restricted sample to college students and journalists in the 40s and film academics in the 80s, Bates can only make the global claims that he does through an enormous leap of faith. But what if there were college professors in 1941 who regarded Rosebud as “dollar-book Freud,” or freshmen and journalists today who take Rosebud seriously? Certainly many of my own students encountering Kane for the first time have less trouble with Rosebud than either Leff or Carringer.

(2) From the Rosebud gag in Hellzapoppin (1941) to comparable gags in the comic strip Peanuts in the 70s, the gradual transformation of Kane from an eccentric industrial anomaly to a “classic” commonplace has undoubtedly altered its meaning and function as an aesthetic object. My own first encounter with Rosebud — at a New England prep school, circa 1960 — is one I regard as having been both healing and cathartic, but not one I could necessarily count on sharing with either my teachers or classmates, whose expressed attitudes toward the film ranged from bored indifference (Wally Shawn, future author and co-star of My Dinner with Andre) to political skepticism (a socialist English teacher) to guarded approval (a liberal English teacher) to comparable enthusiasm (Nick Macdonald, future independent filmmaker). A year or so later, at an introductory film course at NYU, I was dismayed to find Kane absent from the syllabus because the teacher (Haig Manoogian, the future mentor of Scorsese) considered the film vastly overrated and fundamentally uncinematic — a sentiment partially echoed in most of the standard film texts available at the time (Agee on Film, The Liveliest Art, The Film Till Now), but sharply countered by Sight and Sound‘s Winter 1961/62 poll of seventy international critics, which accorded the film first place. My point is that it’s taken this country nearly half a century to “place” Citizen Kane comfortably within a mainstream masterpiece context, a process which could never have happened without an ideological transformation which I will discuss later. And there appears to have been widely divergent responses to the film along the way.

(3) Although Bates tends to collapse journalistic and academic responses to Kane into the same order of discourse, one could argue that each mode of discourse, by operating from a different institutional base, has a different audience and function, hence a different institutional purpose. The different social codes and other institutional determinations of journalism and academic criticism dictate part of their meanings, and it is unwise to quote from either mode to demonstrate “what people think” without allowing for such determinations. Thus the absence of academic film criticism in 1941 is as pertinent to Bates’s discussion as the apparent scarcity of 1941 audience responses to Kane available in 1987.

(4) Contextually and polemically, from the standpoint of my present research, Kane can be read in two diametrically opposed fashions: (a) as the first feature of an independent, avant-garde filmmaker, and the only one in which he was accorded both full range of a Hollywood studio and final cut — hence as an exceptional instance in a filmmaking career fundamentally at odds with the Hollywood mainstream; and (b) as the ultimate vindication of the Hollywood mainstream, showing that major creative talents (including Welles, Mankiewicz, and Toland) could be brought together and exploited to their fullest advantage — hence, in the gospel according to Pauline Kael and others, the best film that Welles ever directed (especially insofar as all the subsequent ones are judged according to the same industrial mainstream standards).

While Bates seems at least partially aware of both possible readings (see his section “Kane as the ‘American Kubla Khan'”), his analysis is grounded in the assumptions of (b) — and understandably so, because this corresponds more closely to the currently more popular academic viewpoint. Kael’s “Raising Kane,” re-produced in The Citizen Kane Book, has, after all, been the only extensive critical text on Welles in English to have remained in print over the past sixteen years. And its popularity relative to the vastly superior texts of Bazin, Carringer, McBride, and Naremore is hardly accidental. But if one believes, as I do, that the healing and cathartic powers of Rosebud have more to do with the assumptions of (a), then a great deal of what fuels these powers is automatically factored out of Bates’s analysis.

In order for Kane to be enshrined in this country, it first had to be redefined as an aesthetic object — placed in continuity with conventional Hollywood practice rather than in opposition to it — and this was a job for which Kael’s temperament and position on The New Yorker made her ideally suited. To accomplish this ideological sleight of hand, she had to minimize much of what made the film oppositional thirty years earlier, including Welles’s status as an auteur and other anti-Hollywood aspects of Kane — such as its pessimism and its unorthodox methods of storytelling — which naturally led to her exaggeration of Mankiewicz’s importance (2), her criticism of the role played by Thompson, and her Procrustean recasting of the film as a newspaper comedy — all of which contrived to re-adapt Kane to Hollywood norms. None of this could have happened if there hadn’t already been a pressing need on the part of the industry itself and its publicists (Kael included) to ward off the threats posed by auteurism, recent European experimentation with narrative forms, and a strong upsurge in self-consciousness about film, all of which were in full swing when “Raising Kane” was published in 1971. To understand the context in which it appeared, one must read it in relation to the then-current debates about auteur theory which had started in the pages of Film Culture and Film Quarterly. To the extent that Kane was then regarded as the ultimate linchpin of auteur theory (rather than of Hollywood or independent filmmaking), Kael’s recasting of the film as a Mankiewicz film directed by Welles and shot by Toland (as opposed to a Welles film which used the talents of Mankiewicz and Toland) was intended to destroy this model and establish the scriptwriter (in this case, a gifted Hollywood hack) as the decisive voice among many. To cinch her argument, she took care to limit her research only to sources on Mankiewicz’s side of the debate (3).

If Bates is correct in his thesis that Rosebud had therapeutic powers in 1941 which are no longer available to us, this may be in part because his father and other 1941 spectators were lucky enough to see Kane long before it was emasculated into a Hollywood commonplace. If he is wrong, this may be because no amount of critical reconditioning can necessarily affect students fortunate enough not to have been exposed to it. Admittedly, we are no longer in the same historical situation as 1941 spectators, but this needn’t necessarily diminish the impact of the sled going up in smoke; ours is still a civilization of conspicuous waste and media buffoonery, of compulsive acquisition and a frustrated longing for vanished roots. If we agree with Thompson that one word can’t explain a man’s life, we can regard Rosebud as Welles did in 1963 — as a vehicle rather than as the ultimate epiphany — and still experience the same furious sense of loss at the end. Kane, after all, gives us a choice — in a way that Kael’s Hollywood entertainment model clearly does not.

Notes

1. See, in particular, “The Invisible Orson Welles: A First Inventory,” Sight and Sound 55 (Summer 1986): 164-171.

2. Reflected not only in her dubious scholarship — see Peter Bogdanovich’s “The Kane Mutiny” (Esquire, October 1972, 99-105, 180-190); Robert L. Carringer’s The Making of Citizen Kane (University of California Press,1985, 17-18,34-35); Ted Gilling’s interviews with George Coulouris and Bernard Herrmann (Sight and Sound 41 [Spring 1972]: 71-73); Barbara Learing’s Orson Welles (New York:Viking 1985, 184, 203-4); Joseph McBride’s “Rough Sledding with Pauline Kael” (Film Heritage 7 [Fall 1971]: 13-16, 32); among others — but also in the very layout of The Citizen Kane Book,which misleadingly uses all its frame enlargements to illustrate Mankiewicz’s version of the script rather than the cutting continuity (which follows in much smaller type).Thus Bates is simply wrong when he attributes the shot of “Kane’s huge lips” uttering “Rosebud” to Mankiewicz’s script, and at the very least misleading when he states that “Citizen Kane started as a screenplay about William Randolph Hearst” by Mankiewicz and Houseman — to cite only two examples of misinformation that can be directly traced back to Kael’s mischief. The fact that Kael made no effort to contact Welles in the course of her research — a logical decision given her ideological project — still couldn’t change the ironic fact that Welles, as legally established co-author of the final script, received royalties on The Citizen Kane Book, despite the fact that Kael’s essay implicitly denied him any authorship at all. (This latter fact was recently confirmed in conversation with Oja Kodar, Welles’s companion and collaborator since the late 60s.)

3. The many exposures of Kael’s scholarly abuses, cited above, have not prevented Kael and her publisher reissuing The Citizen Kane Book in all its subsequent editions with all of its countless errors and underhanded polemics intact. For an analysis of the inadequacies of “Raising Kane” as criticism (which erroneously accepts the word of Kael and John Houseman on Mankiewicz’s sole authorship of the final script), see my own review in Film Comment 8 (Spring 1972): 70-73 (with corrections and additions not pertaining to the authorship debate in Film Comment 8, no. 2: 80).