Written for the 2019 catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. — J.R.

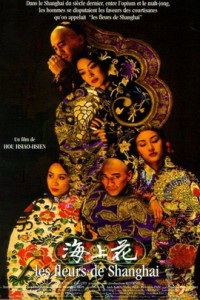

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s 1998 feature, his thirteenth, represents a bold departure from his previous work. It’s his first film to be set completely outside Taiwan, the implicit or explicit subject of his earlier movies — most noticeably in his trilogy comprising City of Sadness, (1989), The Puppetmaster, (1993), and Good Men, Good Women(1995), but also in the bittersweet allegory of Son’s Big Doll, his seminal contribution to the 1983 sketch feature The Sandwich Man. After focusing mostly on families and landscapes, Hou fashions a chamber-piece set exclusively in the interiors of Shanghai brothels in the late 19thcentury, adapted from a novel by Han Bangqing by his usual screenwriter Chen Tien-wen.

And after Hou showed striking stylistic affinities with Yasujiro Ozu, here’s a film whose long takes, camera movements, and concentration on prostitution suggest a Kenji Mizoguchi without melodrama. But insofar as Hou’s previous films deal with existential and historical questions of identity related to Taiwan as a country occupied and colonized at various times and in various ways by China, Japan, and the U.S., Flowers of Shanghai finds similar issues arising from interactions between prostitutes (the “flower girls”), their madams (or “aunts”), and their wealthy and powerful customers.

It’s characteristic of Hou’s distanced approach to power, economics, and sentiment that he doesn’t include actual sex among these interactions, focusing instead on conversations lubricated by food, tea, and opium. He also disperses our attention between various brothels, flower girls, madams, and patrons without persuading us to regard any of them as primary. As the online blogger acquarello has noted, “By confining the scenes to interior shots of the Shanghai flower houses, Hou portrays the created, artificial world – the unsustainable illusion – of the flower house patrons. In essence, the flower houses are an idealized reflection of the patrons’ own ambivalent feelings between love and passion, obligation and generosity, commitment and fidelity. Inevitably, their hermetic environment of lavished wealth and drug-induced escapism cannot prevent the objects of their affection – the emotionally resilient flower girls – from escaping their tenacious, suffocating grasp.”

— Jonathan Rosenbaum