Written for the 2019 catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. — J.R.

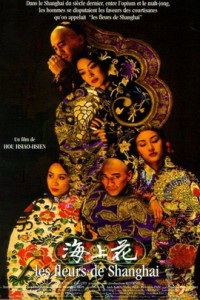

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s 1998 feature, his thirteenth, represents a bold departure from his previous work. It’s his first film to be set completely outside Taiwan, the implicit or explicit subject of his earlier movies — most noticeably in his trilogy comprising City of Sadness, (1989), The Puppetmaster, (1993), and Good Men, Good Women(1995), but also in the bittersweet allegory of Son’s Big Doll, his seminal contribution to the 1983 sketch feature The Sandwich Man. After focusing mostly on families and landscapes, Hou fashions a chamber-piece set exclusively in the interiors of Shanghai brothels in the late 19thcentury, adapted from a novel by Han Bangqing by his usual screenwriter Chen Tien-wen.

And after Hou showed striking stylistic affinities with Yasujiro Ozu, here’s a film whose long takes, camera movements, and concentration on prostitution suggest a Kenji Mizoguchi without melodrama. But insofar as Hou’s previous films deal with existential and historical questions of identity related to Taiwan as a country occupied and colonized at various times and in various ways by China, Japan, and the U.S., Flowers of Shanghai finds similar issues arising from interactions between prostitutes (the “flower girls”), their madams (or “aunts”), and their wealthy and powerful customers. Read more

Commissioned by Caboose Press for a forthcoming volume on Godard and posted here prematurely. — J.R.

François Truffaut

‘Un Trousseau de fausses clés’, Cahiers du Cinéma 39 (October 1954): 45–52.

I have often wondered why my favourite piece of film criticism by François Truffaut — ‘Un trousseau de fausses clés’, the final essay devoted to Alfred Hitchcock that appears in Cahiers du Cinéma No. 39, in October 1954, the first special issue of that magazine devoted to Hitchcock. — has never been included in any of Truffaut’s books. The likeliest reason is that Truffaut begins his article by responding to André Bazin’s essay in the same issue — pointedly called ‘Hitchcock contre Hitchcock’, maintaining that Hitchcock tended to tell his interviewers whatever they wanted to hear — by conceding that Hitchcock was something of a liar. Given Truffaut’s cordial relations with Hitchcock that ultimately led to his book-length interview with him, reprinting an essay that began with and then pondered the implications of such an assertion was something to be avoided.

Even so, the absence of this seminal essay from Truffaut’s ‘official’ critical oeuvre has been unfortunate, especially because it has obscured its importance as a major influence on Truffaut’s critical colleagues—most notably on Éric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol, in their pioneering 1957 book on Hitchcock, which alludes twice to this essay (without, however, providing a specific reference to it) and recapitulates much of its central analysis; on Jean-Luc Godard, in his own most ambitious and exhaustive critical analysis of a film, ‘Le Cinéma et son double’ (Cahiers du Cinéma issue no. Read more

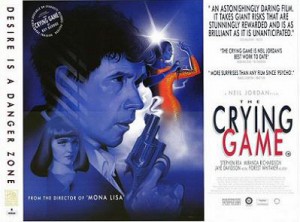

From the Chicago Reader (December 18. 1992). I was reminded of this capsule by Thom Andersen’s references to it when he reviewed The Crying Game at length for the Reader, in an essay reprinted in his excellent recent collection, Slow Writing. — J.R.

An adroit piece of story telling from Irish writer-director Neil Jordan (Mona Lisa, The Miracle) that is ultimately less challenging to conventional notions about race and sexuality than it may at first seem. Like other Jordan features, this one centers on an impossible love relationship, and the covert agenda of the plot is to keep it impossible by any means necessary. The theories of literary critic Leslie Fiedler about the concealed and unconsummated lust of the white male for the nonwhite male in such American classics as Huckleberry Finn and Moby Dick seem oddly relevant to certain aspects of this tale about an IRA volunteer (Stephen Rea) who assists in the kidnapping of a black British soldier (Forest Whitaker) and subsequently becomes involved with his mulatto lover (Jaye Davidson) in London; the plot, held in place by a parable about a scorpion and a frog that’s filched from Orson Welles’s Mr Arkadin, features a startling twist about halfway through; among the cleverly concealed safety nets that hold this movie’s conceits in place is an implied misogyny that only becomes evident once the story is nearly over. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 28, 1997). — J.R.

A pared-down crime thriller set mainly in Reno, this first feature by writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson is impressive for its lean and unblemished storytelling, but even more so for its performances. Especially good is Philip Baker Hall, a familiar character actor best known for his impersonation of Richard Nixon in Secret Honor; he’s never had a chance to shine on-screen as he does here. In his role as a smooth professional gambler who befriends a younger man (John C. Reilly), Hall gives a solidity and moral weight to his performance that evokes Spencer Tracy, even though he plays it with enough nuance to keep the character volatile and unpredictable. Samuel L. Jackson and Gwyneth Paltrow, both of whom have meaty parts, are nearly as impressive, and when Hall and Jackson get a good long scene together the sparks really fly. Pipers Alley. — Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more