From The Soho News, October 6, 1981. I’m embarrassed to confess that over three decades later, I have no recollection at all about Tighten Your Belts, Bite the Bullet apart from what I wrote about it, although I’m happy to report that the film is still in distribution, and available from Icarus Films. — J.R.

September 22: From a global or even a continental perspective, much of this year’s New York Film Festival belongs under the staunch division of Business as Usual. This basically means that the festival is involved in ratifying certain important discoveries (of ideas or filmmakers) that were made during the 60s or 70s, often by the very same members of the selection committee, rather than risking its self-image or self-composure in order to seek out many new challenges or talents.

This makes New York precisely the reverse of the more footloose, friendly, and unpredictable film festival in Toronto. There the specialty tends to be, rather, a flavorsome if occasionally warmed-over newness of look, sound, and/or signature: an underground movie about everyday life in the Watts ghetto (Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep), a corrosive and shocking black comedy about the mourning business in Israel in relation to war memorials (Yaky Yosha’s The Vulture), a flaky German film based on a French best seller about Proust by his maid, played by Fassbinder alumnus Eva Mattes (Percy Adlon’s Celeste). French treats ranged from the florid pyrotechnics and adolescent, operatic passions of a stylish thriller called Diva (a first feature by Jean-Jacques Beineix) — voted the second most popular movie in Toronto after Chariots of Fire, and just picked up for U.S, distribution by the resourceful U.A. Classics) — to the photogenic Pigalle enclosures, funky Renoir (and noir) ambience and staccato actorly patterns triumphing over a dimwitted, disassembled plot in Juliet Berto and Jean-Henri Roger’s Neige (another vivid, watchable first feature that deserves to be seen here).

What’s going on in world cinema? The message of this year’s New York Festival — apart from many welcome standbys, and a few discoveries made elsewhere — is that New York neither knows nor cares. (No wonder it’s the last stop for so many films of interest, after slowly wending their way across the rest of the globe). By and large, and to all appearances – the upcoming premiere of a 16mm Rivette film seems a striking exception — most of this year’s selections have been adroitly tailored to the intellectual limitations of our local mainstream celebrity critics, whose deep and blissful sleep has for the most part been respected and protected. To learn about most intellectually demanding or ambitious work being done outside of America, one simply has to live somewhere else.If the New York Festival once served to deliver a substantial part of the news (e.g., the films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet), this is clearly no longer the case.

That much said, there are still plenty of interesting and important films on view – including all four of those discussed below. Through a perverse relationship between this week’s press shows and Soho News’s copy deadline, all of these will have been shown at the festival before this reaches the stands, but surely (or at least hopefully) they’ll all be seen in these parts again. (Lightning Over Water, for one, will resurface at the Public in late October as part of an extensive Nicholas Rau retrospective, and I would be horrified indeed if New Yorkers were deprived of another look at Tighten Your Belts, Bite the Bullet, which should be made available on every street corner.)

***

In order to access Wim Wenders and the late Nicholas Ray’s Lightning Over Water properly, as a work and as a deed — something that I plan to try to do in these pages at greater length in the near future, in relation to André Gregory, Wally Shawn, and Louis Malle’s My Dinner with André (which is also opening soon) — one has to contextualize it in some detail. One has to see the terms of Ray’s contribution, first of all, in relation the fact that he knew he was dying of brain cancer, and had not brought a feature film to completion ever since 55 Days in Peking virtually finished him in 1963.

It helps, too, if you know that the opening sequence, in which Wenders arrives at Ray’s Spring Street loft, is essentially Ray’s own direction — with a bold use of spatial dialectics between the two characters at opposite ends of the loft that is worthy to stand with his best 50s work. And the last sequence before the (mainly regrettable) epilogue, a close-up of his ravaged face delivering a discontinuous monologue that runs for an entire reel, is no less redolent of the best and worst of his unfinished We Can’t Go Home Again, entirely his own doing, and improvised on the spot. In between these two virtual monuments hangs an ambiguous chasm that seems supervised more by Wenders.

Reading Samson Raphaelson’s moving memoir about Ernst Lubitsch in the New Yorker of last May 11, three days after this press show, I’m immediately struck by the odd parallel whereby a younger cineaste writes a premature obituary for an older cineaste and then discovers, to his chagrin, that he has to thrash it out with him in the present tense. Raphaelson’s existential confrontation (like Lubitsch’s) is, however, recollected in tranquility many years later, while Wenders’ final version comes only two years after the event, and only one year after Peter Przygodda’s first edited version [Nick’s Movie] showed in Cannes and Venice.

Having seen both Przygodda’s version on its way to Cannes and Wenders’ once before, I remain hamstrung in any attempts to come to simple conclusions about the overall experience. But anyone who wants to consider this film in detail should contemplate purchasing the extraordinary large-format volume published by Zweitausendeins in German and English, beautifully illustrated by color frame enlargements from every sequence — currently available at both the Idle Hour and Cinemabilia for about $15. (The film’s producer, Chris Sievernich, informs me that 4,000 of the 10,000 copies printed here have already been sold internationally.)

***

September 24: Over a year and a half has passed since I last saw and enjoyed Maurice Pialat’s Passe ton bac d’abord (Graduate First) at the Museum of Modern Art, and I certainly don’t mind the festival letting me see it again — even if this violates its own supposedly cardinal rule of sticking to New York premieres. An uncharacteristically honest poet of the middle class who can occasionally be almost as brutal about its awfulness as Flaubert, Pialat fully deserves all the attention and praise that the local bozos usually shower on Paul Mazursky and sentimental French hacks. I’d be even happier if the festival dipped back into the recent past and rectified its own previous omission of Pialat’s best film, La Gueule ouverte (The Mouth Agape, 1974) — even if that meant having two terminal cancer movies in one festival –- but you can’t have everything. And Graduate First, which excels in handling such subjects as an endless wedding party and a teenage café hangout called Le Caron, has plenty in its own right.At one point in the movie, a guy in a car asks directions for getting to Rue de Rozier, and a local tells him, “Nowhere near here.” Unless my ears and rampant cinephilia are both deceiving me, this is Pialat’s sly way of distancing himself from the New Wave films of Jacques Rozier (Blue Jeans, Adieu Philippine, Du côté d’Orouët, etc.), which also focus on the antics and exuberance of provincial teenagers, but with a less fatalistic view of social consequences, despite a superficially similar (and lively) surface texture.

The deadly accuracy in Pialat’s case — mainly cheerful, though less buoyant than Rozier — becomes cumulatively oppressive over the course of the film through a plethoraof minor, underplayed details: a glib cocksman with posters of Che Guevara and Emmanuelle in his bedroom, an argument on a beach about the comparative worth of Pink Floyd and Bob Marley, a grinning female flirt in a blue Fruit-of-the-Loom pullover. More healthy in its unstated attitudes toward sex than any recent American movie that comes to mind, Graduate First tends to regard screwing as at once the only worthwhile activity to pursue in the provinces and the greatest obstacle to breaking away from them. Like the shots of graffiti carved into classroom desks combined with the chatter of a philosophy teacher, which open and close the film, Pialat works, as these people live, within narrow and well-defined limits, but within these terms, he’s something of a master.

***

September 25: Grateful as I am to see both the 48-minute Tighten Your Belts, Bite the Bullet and the 54-minute Resurgence: The Movement for Equality versus the Ku Klux Klan in one dynamite double-bill, I can’t help but wonder if the only reason why they’re shown in the above order is that the latter is six minutes longer. I bring this up only because Tighten Your Belts strikes me as conceivably the most intelligent, powerful, and informative rabble-rousing leftist film that I’ve seen in years, and can’t imagine why the festival organizers didn’t want to maximize its impact by showing it second.

The more conventionally conceived Resurgence, codirected by Pamela Yates and Thomas Sigel and costing around $75,000 has the pure documentary value of showing us goony Southern white retards killing anti-Klan demonstrators in Greensboro with impunity, and/or wearing T-shirts with Mickey Mouse giving the finger and saying, “Hey, nigger!” (The Disney studio people who have shown such concern about obscene desecrations of their cartoon animal emblems should certainly alert their lawyers about this one.) It has the integrity, too, of its sentimental good intentions in crosscutting between this material and the struggle of black women and others in Mississippi in organizing against impossible work conditions. A lot of serious work and information is evident here. The only problem is, as critic Ruth McCormick has pointed out to me, extended footage of leftist rallies tends to preach only to the converted, and the film’s a good 10 or 15 minutes longer than it needs to be.

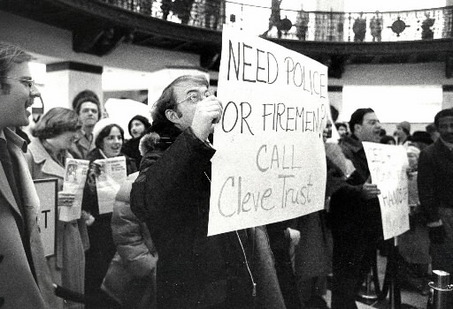

Tighten Your Belts, codirected by James Gaffney, Martin Lucas, and Jonathan Miller over four and a half years and costing a third as much as Resurgence, is a stunning example of how this work and economy can pay off in dividends. Expertly incorporating animation, live-action interviews, and other footage of diverse kinds with a good jazz score (by Nick Scarim), the film has the rare virtue of using all its materials to build a clear linear argument that progresses at every stage. Contrasting the recent fiscal crises in New York and Cleveland and the antithetical approaches taken by their mayors, the filmmakers delineate and document the capitulation of New York to the caprices of banks and the resistance of the city administration of Cleveland to corporate takeover, sparked by the forging of a broad popular front by the exciting Dennis Kucinich.

Exemplary in its clean, polemical construction, Tighten Your Belts, Bite the Bullet deftly incorporates a specific popular struggle – the 18-month campaign in Brooklyn’s Northside to keep a firehouse – into its overall argument, without succumbing to any of the temptations of a political travelogue. In other words, it means business. It sends you out of your seats making you believe that positive change is actually possible – and that if any single force finally succeeds in radicalizing the American working class, it may well be the good ole Reagan administration.