The following essay was commissioned by Toronto filmmaker Ron Mann in 1992 for the book-spinoff of his documentary Grass. I wrote this around the same time that I reviewed Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai for the Chicago Reader, which helped to focus my conclusion; for more aspects of this argument, see “International Sampler”.—J.R.

What Dope Does to Movies

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

To the memory of Paul Schmidt

Consider how the camera cuts from Richie Havens’s face, guitar, and upper torso during his second number in Woodstock (1970) to a widening vista of thousands of clapping spectators, then to a much less populated view of the back of the bandstand, where there’s no clapping, watching, or listening — just a few figures milling about near the stage or on the hill behind it. What’s going on? This radical shift in orientation and perspective—a sudden movement from total concentration to Zenlike disassociation — is immediately recognizable as part of being stoned, and Michael Wadleigh’s epic concert film, which significantly has about the same duration as a marijuana high, is one of the first studio releases to incorporate this experience into its style and vision.

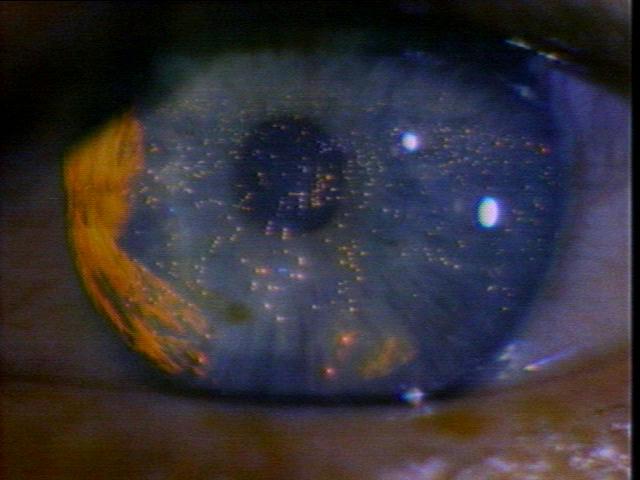

Or think of the way that Blade Runner (1982) starts: a long, lingering aerial view of Los Angeles in the year 2019, , punctuated by dragon-like spurts of noxious yellow flames, with enormous close-ups of a blue eye whose iris reflects those sinister, muffled explosions. Or consider the zany, spastic contortions of Steve Martin en route to an elevator in All of Me (1984) — torn schizophrenically between his own identity and that of a recently reincarnated Lily Tomlin. Two hostile forces and divided wills twist is elastic, string-bean body into a wild succession of contradictory jazz riffs, a riddled battlefield careening this way and that under opposing orders.

Better yet, contemplate the hallucinatory special effects and the screwy changes of tone in Joe Dante movies like Gremlins (1984), Matinee (1993), or Small Soldiers (1998), the wide-angle distortions and fantasy premises of films like Bob Balaban’s Parents and Raul Ruiz’s Three Lives and Only One Death (1996), or the ambiguous netherworld between thoughts and realities comprising Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

All of these experiences have something to do with dope. None of them would look or sound or play the same way today if marijuana hadn’t seized and transformed the style of pop movies thirty years ago. This isn’t to say that the filmmakers in question are necessarily teaheads, or that the people in the audience have to be wigged-out in order to appreciate these efforts. Stoned consciousness by now is a historical fact, which means that the experiences of people high on grass have profoundly affected the aesthetics of movies for everyone: filmmakers and spectators, smokers and smokers alike.

It all started around the same time that movies as a whole got shaken up. Exploding Sixties culture opened up the way to all sorts of outside influences. From England came the Beatles and the Rolling Stones; from France came the New Wave movies of Godard, Resnais, Rivette, and Truffaut; political models were exported from China and Cuba, religious models from India and Japan. Meanwhile, the herbal emblems of certain American minorities — the peyote of Indians, the reefers of blacks — got tossed into the same heady stew, adding a congenial flavor to all the rest.

What did dope do to the movies, exactly? First of all, it changed the ways that people looked and listened. Then it altered the ways that they accepted what they saw and heard:

In Los Angeles, among the independent filmmakers at their midnight screenings I was told that I belonged to the older generation, that Agee-alcohol generation they called it, who could not respond to the new films because I didn’t take pot or LSD and so couldn’t learn yet to accept everything.

This is Pauline Kael, writing in 1964. The article in question is the introduction to her first collection of movie reviews, an essay which is significantly subtitled, “Are the Movies Going to Pieces?” Clearly alarmed at the gradual erosion of audience interest in coherent, well-turned narratives and the growing enthusiasm for jazzy innovations from abroad, Kael could already see a relation between this shift in taste and the widening popularity of grass over alcohol, a change that was generational as well as cultural. Appropriately enough, this revelation took place at a midnight movie — one of those dark, damp retreats of the Sixties where stoned consciousness first came into full bloom. As J. Hoberman and I explored at some length in the book Midnight Movies, marijuana and midnight screenings have nearly always been closely interconnected, if only because dope generally helps to foster a wider and more hedonistic spirit of aesthetic openness.

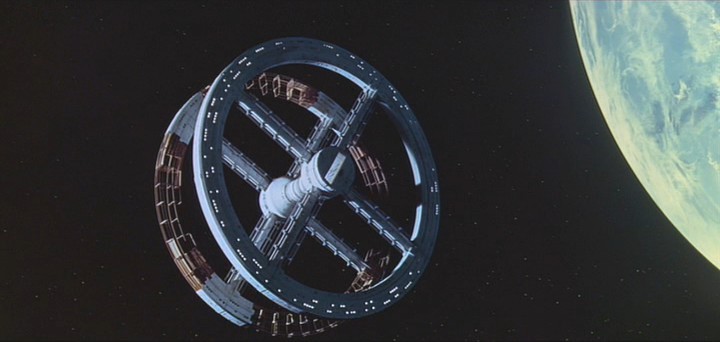

For many experimental filmmakers, the requirement placed on most films to tell a story often stands in the way of other possible pleasures that movies can impart. The tendency to savor individual moments which pot encourages, sometimes at the expense of the whole — a trend towards fragmented experience which TV has also promoted — made consistent and realistic storylines less obligatory than they had been in previous decades. The qualities of pure spectacle found in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and diverse psychedelic fruit salads such as Fellini’s Satyricon and Performance (both 1970) were generally dismissed and disparaged by Kael and other members of her generation. But potheads passionately embraced these movies, caring more about what they had to show than what they had to say. Another older critic, Andrew Sarris, revised his negative opinion of 2001 somewhat after he returned to the film with the aid of a little herbal stimulation, and the fact that he could report on such an undertaking without embarrassment in the Village Voice is emblematic of the relative freedom and relaxation of that period.

With the advent of such purely visual masterpieces of the late Sixties as 2001, Point Blank, and Playtime, movies were beginning to resemble such purely aural experiences as record albums by the Beatles and Frank Zappa over the same period. They were becoming environments to wander about and wallow in, not merely compulsive plots that you had to follow, and sustaining certain contradictions — two-tiered forms of thinking where the mind could drift off in opposite directions at once — was part of the fun they were offering.

Other older critics retracted their original harsh judgements of Bonnie and Clyde (1967) aftyer the film went on to become a box office smash with the youth market. Now here was a movie that had a detailed storyline — but one that was subject to frequent and abrupt changes of tone, as in Godard’s Breathless and Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player, where slapstick comedy and nostalgic romance alternated with tragic bloodbath violence. Just as a doper’s stoned rap might veer in mid-sentence from a consideration of life to a consideration of toenails, movies were getting redefined as an art of the present tense where theoretically anything could happen, regardless of whether or not everyone in the audience came along for the ride.

The same year that Kael first acknowledged the influence of dope on film taste, Susan Sontag published her “Notes on Camp,” which bore witness to a closely related phenomenon – the ironic appreciation of sincere art that was outrageously overblown. Sontag’s examples ranged all the way from Shanghai Express to King Kong, expressing new routes to pleasure that could bypass the usual barriers between high and low forms of art. And if camp taste probably owed as much to gay sensibility as the learned pleasures of pot owed to black culture, there was a way in which these two minority interests often worked hand in glove. Consider the lasting success of Reefer Madness as a midnight camp classic long after it was released in earnest in 1940; and by the same token – or toke –one should add that stoned amusement helped to pave the success of such deliberate camp efforts as Female Trouble and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, not to mention other midnight staples including The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Eraserhead, and George Romero’s “Dead” trilogy.

If Robert Altman’s movies in the early Seventies –- M*A*S*H, Brewster McCloud, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye –- reveal the overall impact of dope on movie consciousness, representing a halfway house between the softer dope influence of the Sixties and the harder edge it would take on in the early Seventies –- this is because they reflect so many of the stylistic changes reflected above, at the same time that they frequently allude to drugs in their plots. The use of overlapping dialogue and offbeat musical accompaniments (such as the Leonard Cohen songs in McCabe, the bird lectures in McCloud, and the multiple versions of the title tune in The Long Goodbye) created a dense weave that made each spectator hear and understand a slightly different movie -– and, given that these were crowded, widescreen features, see a different movie as well. These movies were all spaced-out experiences which presented both bright communal activities (from army pranks to patriotic rallies to frontier-town gossip to hash brownies) to lonely, deranged individuals who stood outside these mystiques and pursued dreamy head-trips of their own. As a spectator, one was invited to identify with both positions -– hearing the local prattle about whorehouse owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) and his legendary prowess with a gun, and sharing the same character’s tongue-tied awkwardness and experience. Drifting between these contradictory options, one navigated one’s way through Altman’s languid zooms and uncentered camera movements like a doper gliding through different trains of thought, comically stumbling (like many of the characters) through hallucinatory environments where nothing was ever the way one assumed it to be.

***

…I occasionally use marijuana in preference to alcohol, and have for several decades. I say occasionally and mean it quite literally; I have spent about as many hours high as I have in movie theaters — sometimes 3 hours a week, sometimes 12 or 20 or more, as at a film festival — with about the same degree of alteration of my normal awareness. —Allen Ginsberg, 1965

Let’s say that early period [up through Pierrot le fou] was my hippie period. I was addicted to movies as the hippies are addicted to marijuana, but I don’t need to because movies are the same to me….[and] now I’m over this movie marijuana thing. —Jean-Luc Godard, 1969

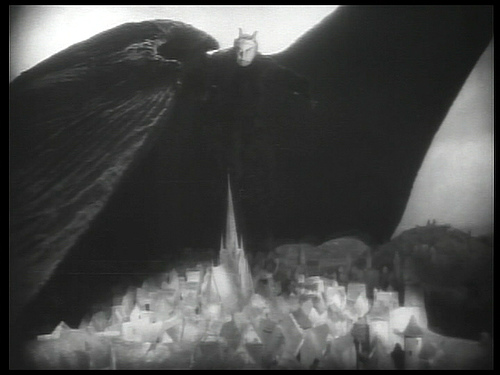

In more ways than one, The Movie as Trip profoundly altered the social trappings and atmosphere of filmgoing as well as the more purely formal and aesthetic aspects of the experience. in contrast to the quintessential communal experiences of movies like Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, and Casablanca — movies for and about communities — the no less emblematic 2001 of the Sixties and Apocalypse Now of the Seventies made each spectator the hero of a new kind of drama, which was staged inside someone’s head. In some ways this environmental experience could be attributed to tapping the atmospheric possibilities of Dolby sound, but in other respects it might be regarded as a throwback to the German Expressionist movie tradition that characterized such silent classics as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis, Faust, and Sunrise, and which subsequently became more Americanized and mainstreamed in certain Disney cartoon features like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio — not to mention Orson Welles’s live-action Citizen Kane.

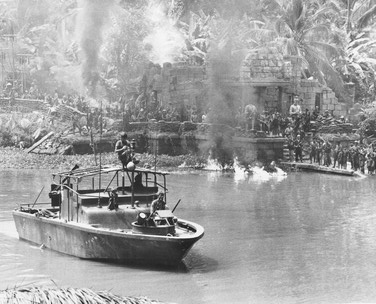

You might even say that travelling down the river in Apocalypse Now — a movie whose origins can be traced in part back to Welles’s unfulfilled first Hollywood project preceding Kane, to adapt Joseph Conrad’s “Heart odf Darkness” in terms of the present, with the camera taking the role of Marlow — was a little bit like taking a ride in Disneyland and Disney World, remaining passive and mesmerized while a parade of marvels and surprises glided past you or were heard from surrounding speakers. Whatever was happening was happening to you, the spectator, first of all, the character of special agent Benjamin L. Willard (Martin Sheen) only secondarily, and the drugged-out ambience of the trip as a whole — derived in part from Michael Herr’s remarkable evocations of pot-drenched Vietnam combat experiences in his book Dispatches — made the surreal fantasy element that much stronger. Alas, this made the meaning of the war in Vietnam for the Vietnamese even more remote from American experience than it already was; the “real” drama of Apocalypse Now had little to do with the suffering and struggle of the native population and everything to do with Francis Ford Coppola, the viewer’s true surrogate (who was actually shooting in the Philippines), penetrating the “heart of darkness” like Conrad’s Kurtz and Marlow.

Screened at midnight, marihuana-drenched movies might have been experienced communally, but in more mainstream venues one could argue that they tended by design to atrophy into more private trips. To a certain extent, subsequent blockbusters like the Star Wars and Indiana Jones trilogies reflected some of the same amusement-park tendencies, because by this time video games and home viewing were beginning to replace theatrical screenings as the main form of movie experience.

This transition had something to do with dope, but was affected still more by the implicit social philosophies of the respective periods, which also helped to determine how dope was smoked. What began in the Sixties as an almost tribally shared collective pastime — being stoned at the movies — passed through the Me generation of the late Seventies to become a more private and individualized experience in the Eighties and early Nineties. Seeing a movie like the recently revived Yellow Submarine — a feature-length cartoon set to Beatles songs — back in 1968, in any large U.S. theaters that tolerated toking (and there were plenty of those back then), you virtually had a guarantee of getting at least a buzz whether you brought along joints or not. The air would be so thick with smoke that you could walk through sample whiffs of various grades on the way to your seat, getting slightly glazed in the process. because it was more fashionable back then to share smoke with strangers, roaches were more prone to be passed down the aisles, creating a kind of spider’s web of complicity between the different people in the audience, as well as between them and the events on screen.

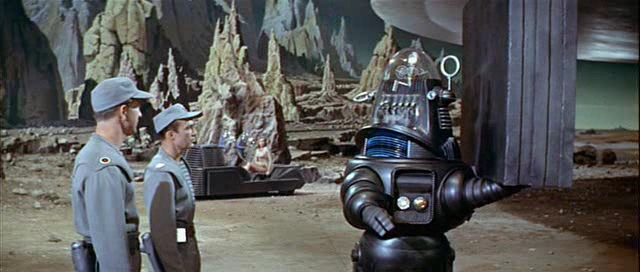

As grass-smoking gradually returned to the living room, bedroom, and bathroom, where it first took hold in the Sixties before the pastime became public, this return to relative privacy — a high to be shared with friends, but not with strangers — was reflected in the more insular and insulated pop movies that came out. Compare 2010 to 2001, The Cotton Club to Singin’ in the Rain, Dune to Forbidden Planet, Gimme Shelter to Woodstock: in each case the social context becomes narrower while the individual head-trip looms larger. Taking the movie home with you on video or DVD not only keeps you off the streets; it also leaves the movie untested as a site for social interaction, hence less amenable to certain collective experiences — unless one finds a way of making it more interactive again.

Perhaps only with the current global interconnections of the internet and email are we beginning to return to comparable kinds of complicity in relation to movies — the renewed notion of a tribal community, reconfigured this time not in terms of viewing movies but in terms of discussing them and related subjects (and sometimes in terms of finding and swapping certain movies on DVD). Interestingly enough, this may also be affecting movie content; the fantasy-driven contradictions that dope-enhanced and dope-influenced movies used to embrace are making a welcome comeback, only this time they could just as well be labeled cybernetic as psychedelic in impulse — and the influence of musical sampling could be equally important. Who says that Forest Whitaker can’t play a New Jersey samurai operating according to ancient warrior codes and working for the Mafia, in Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog? Twenty years ago the conceit would have been labeled a doper’s reverie; today it still can be read that way, but it also sounds like a fantasy hatched on the internet.

(An early version of this article appeared in High Times, March 1985; revised and updated, March 2000)

–included in Grass: The Paged Experience (based on the film by Ron Mann), Toronto: Warwick Publishing, 2001, 118-122