This appeared in the April 6, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. Although my favorite Cecil B. De Mille film is the talkie version of Dynamite (1929) — I still haven’t seen the silent version, released around the same time — The Ten Commandments (1956) is probably the film of his that I’m most familiar with, along with the somewhat underrated Samson and Delilah (1949).

Part of what’s so remarkable about the scandalously underrated and neglected Dynamite [see still, above] is how real and serious it contrives to make the marital pairing of a coal miner (Charles Bickford) and a spoiled city heiress (Kay Johnson), even though brought about through preposterous plot contrivances, and how, in spite of De Mille’s conservative social and political biases, it assigns equal amounts of dignity and vulnerability to both classes. It’s also one of the most suspenseful and charged melodramas to have ever come out of Hollywood. — J.R.

The Power of Belief

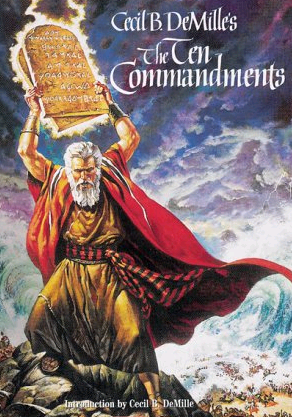

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Cecil B. De Mille

Written by Aeneas Mackenzie, Jessie L. Lasky Jr., Jack Gariss, and Frederic M. Frank

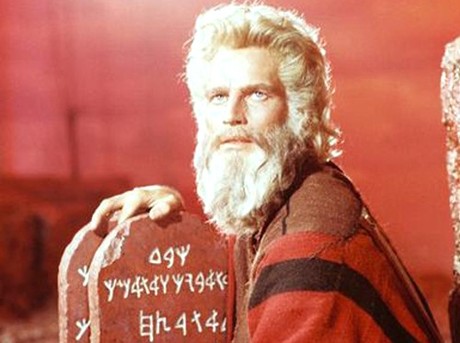

With Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, Yvonne De Carlo, Debra Paget, John Derek, Cedric Hardwicke, and Vincent Price.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Technological developments in communications are nearly always regarded as advancements rather than regressions, yet it might be argued that these advancements have little to do with what we actually have to communicate. By trusting new toys more and more, either as precision instruments or as sophisticated armaments, we seem to be trusting ourselves less and less, and it’s even possible that our growing worship of state-of-the-art sound and image may indirectly point toward a shrinking faith and confidence in what sounds and images are supposed to mean.

The special effects that audiences thrilled to in the 1950s (and earlier) can seem archaic and faintly embarrassing to most audiences today. But the emotions and ideas behind many of these special effects may seem less dated––not because of any ideological sophistication, but because of a fundamental belief in the transparency of sounds and images: an innocent faith in the capacity of special effects to convey emotions and ideas, and not merely effects.

Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), recently rereleased and playing at the Music Box this week, offers an impressive demonstration of this difference –- as well as the best movie blockbuster around at the moment. Its running time is 220 minutes, not including De Mille’s personal introduction and an intermission; much of it looks as ridiculous to me now as it did when I first saw it at the age of 13; but not even a moment of it is boring. It sails along with a breadth and sweep rarely found nowadays at the movies, and one’s eyes are constantly rewarded; this is moreover a highly personal epic –- De Mille’s stamp is visible on every frame.

This absence of longueurs obviously has a lot to do with De Mille’s power as a storyteller and master showman, the kind of power that understandably makes him one of Steven Spielberg’s idols. Central to this power is a sincerity that can’t be found in either Spielberg or any of his master-builder contemporaries, all of whom seem to have a lot more trouble distinguishing their (visible) beliefs from their calculations and manipulations. De Mille’s beliefs are primitive and at times deliriously confused, but there’s never any question that they’re genuine; they exist quite independently of any impact that he wants them to have. There’s plenty of reason to scoff at some of them––for reasons that I’ll get to shortly –- but there’s no basis at all for doubting their authenticity. And because De Mille’s faith in his medium is as unswerving as his faith in the Old Testament, there’s a conviction behind his entertainment that is unmatched by contemporary movies that reach for equivalent forms of uplift, all of which seem to be predicated on negotiations between varying degrees of disbelief.

It’s a tribute to the power (if not exactly the wisdom) of De Mille’s beliefs that not even the hardiest efforts of the gremlins at Paramount Pictures to muck up his achievement have fully succeeded. They’ve taken this feature made in VistaVision and capriciously stretched it out into an anamorphic ‘Scope format, which means that the top and bottom of every frame is trimmed in order to accommodate the horizontal Band-Aid-shaped format –- a familiar shape in 50s movies, but not the one that this picture was shot or originally shown in. There may be some form of divine retribution at work here; De Mille was a notorious foot fetishist, and thanks to Paramount’s skullduggery, many of De Mille’s foreground players are now deprived of their feet. But as far as I can tell, all his other obsessions manage to ring loud and clear, and the glorious, wide-ranging Technicolor palette of Loyal Griggs’s cinematography –- a feast for the eyes that makes every current Hollywood movie look like oatmeal by comparison –- is otherwise preserved intact.

De Mille was every bit as adroit as any of his disciples at manipulating the public perception of his oeuvre. He is known today as the master –- perhaps general on the order of Patton or MacArthur would be more accurate –- of the biblical spectacular, to the same degree that Alfred Hitchcock is known as the master of suspense. But even the most cursory look at his filmography reveals quite a different emphasis. According to the French critic and filmmaker Luc Moullet in a recent survey of De Mille’s work, only eight and a third of his features are “historical-religious” (the one-third being the lengthy prologue to the 1923 silent version of The Ten Commandments, which is otherwise set in modern times), while 26 are adventure stories and another 25 are contemporary comedies or dramas.

But De Mille preferred to be remembered as a popularizer of the Scriptures, and, as with many other things, he managed to get his way. Charles Higham, the author of a rather sycophantic De Mille biography published in 1973, indirectly suggests part of the reason for this determination when he notes, “A deeply committed Episcopalian, [De Mille] literally accepted every word of the Bible without question, and went on record as saying that every word of it with the exception of the Book of Numbers could be filmed exactly as it stood.” An unfortunate consequence of this reputation –- enhanced by the more obvious aspects of De Mille’s profile as a staunch antilabor Republican and spearhead of the Hollywood blacklist -– is a neglect of those portions of his work that don’t match up precisely with this image. Indeed, much of his best nonreligious work cries out for rediscovery; his first two sound films, which were shown recently on the cable channel TNT, Dynamite (see photo, 1929) and Madam Satan (1930) –- both of them highly sophisticated comedy-dramas dealing with wealthy flappers –- reveal talents, including subtleties and nuances, that are scarcely hinted at in such later elephantine (if enjoyable) efforts as Samson and Delilah (1949) and The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). And a closer look at certain aspects of The Ten Commandments suggests that the traditional view of De Mille as a vulgar exploiter of sex and spectacle over substance, while not entirely off the beam, is still an oversimplification. It might even be argued that some parts of this film are antisex and antispectacle, and that a certain religiosity actually constitutes its substance.

Like Hitchcock and Disney, De Mille managed to impose his own persona on the public image of his work to the point that it outshone even his actors. To the best of my recollection, the ten-minute preview for The Ten Commandments shown in 1956 focused in its entirety on De Mille himself in his office talking about the movie –- at one point showing a photograph of a spectacular Mount Sinai sunset that greeted his film crew, suggesting discreetly, perhaps, God’s own stamp of approval on the production. It seems that a major reason why he chose to remake this picture as his swan song was his desire to shoot it on location. His intentions to do so in 1923 were blocked by Adolph Zukor, and his installation of 2,500 people and 4,500 animals in a military-style compound dubbed Camp De Mille was in effect a dress rehearsal for his full-scale invasion of the Holy Land three decades later, which engaged 12,000 people and 15,000 animals for the exodus from Egypt alone.

De Mille’s personal investment in the production was such that he persisted in directing the film against his doctor’s orders after suffering a heart attack, and all of his profits from the film were donated to charities. And in the film itself, after appearing before the story proper to introduce the picture and explain its contemporary relevance (as well as warn the audience about its running time), he continues offscreen as narrator, so that we’re constantly aware of him as a moral presence.

When he appears at the beginning in front of a gold-tasseled curtain to speak his piece, his two main points are that (1) because the Bible omits 30 years of Moses’s life, other ancient sources such as Philo and Josephus have been called on to fill in the gaps, and (2) “The theme of this picture is whether man should be ruled by God’s laws or whether man should be ruled by the whims of a dictator like Ramses.” With his use of the word “dictator” De Mille is clearly evoking such cold-war demons as the recently deceased Stalin and Mao Tse-tung -– especially the latter, considering the orientalism suggested by Yul Brynner as Ramses.

I haven’t had a chance to check out Philo and Josephus, although I strongly suspect that their contributions to the picture are relatively minor. (The film’s credits also cite material from such books as Dorothy Clarke Wilson’s Prince of Egypt, Reverend J.H. Ingraham’s Pillar of Fire, and Reverend A.E. Southon’s On Eagle’s Wings.) I have, however, gone back to all 40 chapters of Exodus in the King James version –- as I’m sure the film was meant to encourage me to do –- and have discovered to my amazement that De Mille’s adaptation has even less to do with this source than, for instance, the movie Bright Lights, Big City has to do with Jay McInerney’s novel of the same title. Paradoxically, in spite of the film’s sincerity, it is full of deceptions; a considerable part of the story seems to have come directly out of De Mille’s head. (Although he receives no script credit, there seems to be a general agreement among De Mille’s biographers and critics that he made important creative contributions to all his major screenplays.)

To start with the nine leading cast members cited at the head of this review, only two of them –- Charlton Heston as Moses and John Derek as Joshua –- play characters corresponding to characters with the same names in Exodus (Moses’s wife Zipporah can be counted as a third if one accepts Yvonne De Carlo’s Sephora as a phonetic equivalent); both of these figures, especially Joshua, are given biographies that are largely fanciful, and most of the others have no direct counterparts in the Bible at all. Moreover, with the exception of Edward G. Robinson, not one of the major Hebrew characters is played by a Jewish actor.

The pharaoh of Exodus is split into two characters, Sethi (Cedric Hardwicke) and his son Ramses (Yul Brynner). Nefretiri (Anne Baxter), who forms a love triangle with Moses and Ramses before she begrudgingly marries the latter and bears his son, has no counterpart at all in the Bible, but a major function in the movie –- she provides the principal sex interest and, not coincidentally, the closest thing in the movie to a pure villain. (Sadistic, vengeful, and murderous, she goads Ramses through constant nagging into his most self-destructive actions.)

Nefretiri’s only rival in the film’s sexual hierarchy is Joshua’s girlfriend Lilia (Debra Paget), a somewhat more sympathetic character –- she is, after all, a Hebrew, not an Egyptian –- who also has no biblical counterpart. Lilia winds up as the concubine of the only completely unsympathetic male character — a creepy informer and small-time Hebrew demagogue called Nathan (Robinson) –- in order to save Joshua’s life (”What would you do to gain his clemency?” “Anything, my lord, anything!”) It’s never clear whether she reunites with Joshua after the Hebrews leave Egypt, but the implication is that she won’t because now she’s damaged goods.

As the above details imply, the true opponent of God’s law in the film, despite De Mille’s introduction, turns out to be not so much communism as unbridled libido. Moses’s major obstacle in accepting his destiny seems to be the hots that he feels for Nefretiri, and Ramses’s major obstacle in accepting the Hebrew god seems to be his kvetching wife; Nathan’s greed for worldly goods is almost indistinguishable from his lust for Lilia. As far as the two pharaohs are concerned, Sethi is a sweet old codger whose heart is broken by Moses’s disobedience and betrayal, while Ramses steadily gains our sympathy as the unfavored son who can never satisfy either his father or his wife, try as he might. (While he and Moses are never seen as teenagers, there’s more than one emotional echo of East of Eden, which was released the previous year, with Brynner in the James Dean part.) De Mille himself was so much of an authoritarian on the set that perhaps he finally couldn’t bring himself to hate the dictators his film was supposed to be denouncing; disapproval was about the most he could muster.

The clearest change that takes place in Moses after encountering the burning bush is that he immediately becomes desexualized, and he remains that way for the rest of the picture. As Sephora puts it to Nefretiri around the time of the first Passover, “You lost him when he went to seek his god; I lost him when he found his god.” (According to Exodus, Moses was already 80 when he turned his shepherd’s staff into a serpent to impress God’s will on Pharaoh; De Mille, working with Heston in his early 30s, makes him seem about half that age when he pulls the same trick, but not a very randy 40.) Regrettably but characteristically, the only nonguilty representations of sex in the movie provide the two campiest moments: Nefretiri’s line, “Oh, Moses, Moses, you stubborn, spiteful, adorable fool,” and the dance of Sephora’s six sisters for Moses (who is invited to select one as his wife) –- all of them nubile, giggly Valley girls.

In short, much of the fascination in The Ten Commandments today, apart from its seductive sweep as pure story telling, has to do with the way it reproduces the sexual unconscious of 50s conservatism. The pagan worship of the golden calf, for instance, is mainly conceived as an old-fashioned orgy indulged in by the mindless masses, despite some perfunctory references in the dialogue to a “god of gold.” De Mille repeatedly intercuts this revelry with God’s two-fisted delivery of the Ten Commandments on top of Mount Sinai –- each commandment recited in a gravelly voice from a tower of yellow-and-orange fire and hitting the side of the mountain like a comet –- but the effect of any dialectic between this spectacle and the one going on down below is largely undercut by the visual evidence that De Mille is both fashioning and worshiping his own god of gold. The theory may be that Moses/De Mille on the mountain is receiving the truth while Nathan, whipping up the crowd around the golden calf into a delirious frenzy, is behaving like a corrupt Hollywood producer, but in practice the difference seems to be patriarchal dictates versus indiscriminate sex.

As for the special effects in The Ten Commandments:

(1) Surprisingly enough, the grandfather of the disaster film spares us most of the plagues of Moses, including the locusts, frogs, lice, and flies, the outbreak of boils, the destruction of cattle and grains, and the fall of darkness; all we get, in fact, are the hailstones and the killing of the firstborn –- which further suggests that spectacle for its own sake is not really part of De Mille’s agenda.

(2) Most of the special effects, including the delivery of the Ten Commandments, are more effective as pure spectacle in the silent 1923 version (now available on video), perhaps in part because they don’t have to contend with such aural considerations as what God’s voice is supposed to sound like. (The parting of the Red Sea is an arguable exception, although here as elsewhere De Mille pretty much reproduces some of the same camera setups.)

(3) The relative ineffectuality of the special effects in the 1956 version, many of which depend on simple animation, can be defended on some grounds as a strength rather than a weakness in terms of the film’s overall impact. As Luc Moullet put it in his original review of the film in Cahiers du Cinéma: “I especially admire the special effects because they are represented without hypocrisy as special effects. . . . What’s the point of silly verisimilitude? The Bible would gain nothing from it.”

Published on 06 Apr 1990 in Chicago Reader, by jrosenbaum